- Introduction to Gender Role Conflict (GRC) Program

- Overall Information about GRC- Books, Summaries, & History

- Gender Role Conflict Theory, Models, and Contexts

- Recently Published GRC Studies & Dissertations

- Published Journal Studies on GRC

- Dissertations Completed on GRC

- Symposia & Research Studies Presented at APA 1980-2015

- International Published Studies & Dissertations on GRC

- Diversity, Intersectionality, & Multicultural Published Studies

- Psychometrics of the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS)

- Factor Structure

- Confirmatory Factor Analyses

- Internal Consistency Reliability Data

- Internal Consistency & Reliability for 20 Diverse Samples

- Convergent & Divergent Validity of the GRCS Samples

- Normative Data on Diverse Men

- Classification of Dependent Variables & Constructs

- Authors, Samples & Measures with 200 GRC Guides

- Correlational, Moderators, and Mediator Variables Related to GRC

- GRC Research Hypotheses, Questions, and Contexts To be Explored

- Situational GRC Research Models

- 7 Research Questions/ Hypotheses on GRC & Empirical Evidence

- Important Cluster Categories of GRC Research References

- Research Models Assessing GRC and Hypotheses To Be Tested

- GRC Empirical Research Summary Publications

- Published Critiques of the GRCS & GRC Theory

- Clinically Focused Models, Journal Studies, Dissertations

- Psychoeducation Interventions with GRC

- Gender Role Journey Theory, Therapy, & Research

- Receiving Different Forms of the GRCS

- Receiving International Translations of the GRC

- Teaching the Psychology of Men Resource Webpage

- Video Lectures On The Gender Role Journey Curriculum & Additional Information

Situational GRC Research and Models: Introduction

In this section of the web page, how to increase the number situational -contextual research studies is discussed.

The following content is presented: a) criticism that situational research has not been completed on GRC, b) theoretical rationales for situational research, c) examples of GRC situations, e) four new research models to conceptualize situational research, f) GRC hypotheses and situational contexts, and g) brief abstracts of past situational research

The situational contexts of GRC is one of the most under developed areas of GRC research. Limited research exists on the causative dynamics of GRC, developmentally, interpersonally, and situationally. Only a few studies have examined how positive and negative situational dynamics interact with men’s and women’s GRC and psychological problems.

Situational research can extend the typical correlational, moderation, and mediation studies most frequently published in the psychology of men. GRC research needs to do more than predict relationships with dependent variables, but assess the complicated dynamics of how men learn and experience GRC.

Situational research on GRC assesses how men “do gender” and how they react to others doing the same. It is about the triggers in the environment and within the man that causes conflict and stress. The situational question is “How, when, and why does GRC occur in men’s lives”? In other words, how and why does GRC cause men psychological problems? What situational variables moderate and mediate the relationship between GRC and those problems?

Directions is needed in designing more complex situational studies including the causes, dynamics, and outcomes of GRC. Furthermore, studies are needed on how men positively adapt to gender conflicted situations or show flexibility in their response to it. To advance situational research, new versions of the GRCS may be needed. This file is in evolution, under revision and incomplete.

Criticism of Gender Role Conflict Research

Critics have discussed the limitations of past GRC research by indicating that much of the past research has been correlational; showing significant relationships between the patterns of GRC and dependent variables. The simplicity of the studies and the low to moderate correlations suggest additional variables need to be studied to explain men’s GRC.

Critics have minimized the importance of GRC correlational research but for theory to be developed correlational relationships between GRC and emotional-psychological problems are first needed for testing moderating, mediating, and situational-contextual variables. Therefore, I understand the critic’s comments about the research just being simple correlations but that is where we start in hypothesizing more complex empirical tests. Moreover there have been over 40 moderator and mediator studies completed demonstrating the effects of third variables explaining men’s GRC. These studies have documented that GRC is affected by many different factors suggesting complexity in understanding its impact in men’s lives.

Critics have argued that men’s GRC has not been contextualized; meaning the situational and real life contingencies of men’s lives have been neglected in GRC theory and research (Addis, Mansfield, Sydek, 2010; Jones & Heesacker, 2012; O’Neil, 2008 a, b; Smiler, 2004). These critiques have been helpful and some have been addressed (O’Neil, 2008, 2015; O’Neil & Denke, 2016) by including six contextual domains, 18 contextual hypotheses, and multiple contextual research models (See Appendix A for these domains, hypotheses, and contexts)). The domains and hypotheses have contextualized GRC, but the critiques have called for more precise assessment of men’s behavior from a micro-contextual or gendered social learning perspective.(Addis et al., 2010; Jones & Heesacker, 2012). Addis, et al., (2010) proposed the gendered social learning research approach that promotes a contextual and contingent-based, cue-oriented agenda for studying gender-relevant behavior. A second contextual approach is what Jones and Heesacker (2012) call the study of “micro-contexts” of men’s issues—that is, sets of cues, norms, and outcome expectations associated with a temporally limited environment. The term, micro-contexts is used to distinguish “brief experiences from the broader contextual factors associated with people’s cultural and subcultural experiences” (Jones & Heesaker, 2012, 295). Both of these perspectives combined with other theories of contextual research (Hayes, 1993; Hayes, Hayes, Reese, & Sarbin, 1993; Ford & Lerner,1992; Deuax & Majors, 1987) are important in expanding the situational aspects men’s GRC and masculinity ideologies.

Theoretical Context for Situational Research On GRC

The theory and research models published in the 1980s’ and 1990s’(O’Neil, 1981, a, b; O’Neil, 1982, 2008; O’Neil et al., 1986; O’Neil, Good, & Holmes, 1995) are relevant to situational research, but they do not provide a coherent, heuristic, or action oriented framework to explain how men’s problems develop from restrictive gender roles in actual situations. The causal questions of how, why, and when a man becomes conflicted with his gender roles were not addressed by the earlier GRC models (O’Neil, 1981 a, b).

To implement situational research the theoretical rationales are needed that situations predict GRC as a mediator or outcome variable? Without compelling rationales for how situations relate to GRC as either a mediator or outcome variable the results would be difficult to conceptualize and explain. I am working on these rationales currently and they are still somewhat under developed. The critical question is how do gender related situations cause GRC or how does GRC mediate negative, psychological outcomes for men in these situations. What situational contingencies and intrapersonal and interpersonal processes related to masculinity and femininity do men experience that result in GRC? Without answers to this question this kind of analysis, masculinity related problems may not be differentiated from other explanations for men’s problems.

The earlier research and theoretical models (See O’Neil, 1981, a, b, 1982, 2008, 2015) , GRC was exclusively a predictor with other variables either being either moderators or mediators. Only recently have micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts been recommended as predictors with GRC either being a mediator or outcome variable (See O’Neil, 2015, O’Neil & Denke, 2016) for these new models). Even with these most recent models, a theoretical rationale for situational dynamics has been lacking. Situational theory about GRC is needed to design and implement studies that assess real life experiences with GRC.?

A Situational, Mediational Contextual Model of GRC

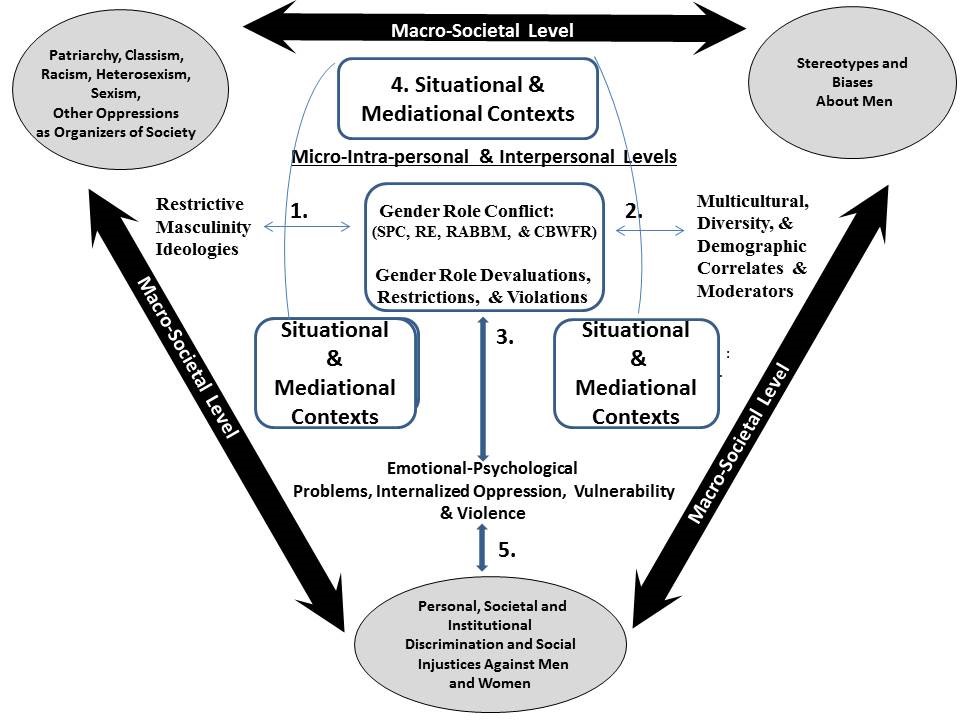

Based on the above assumptions and criticism, a situational model is shown in Figure 1 that connects the macro-societal and micro-interpersonal dimensions of men’s lives. The numbers in Figure 1, positioned close to each arrow convey a correlational relationship between the micro-intra-personal and interpersonal factors. These numbered lines are operationalized in terms of specific research questions that are relevant to advancing GRC theory and research.

The outer triangle in Figure 1, the macro-societal level of analysis, connects patriarchy, sexism, and other oppressions as organizers of society with stereotypes, biases about men, discrimination, and social injustice. The macro-societal context is defined as the social, political, economic, and religious systems based on patriarchy that negatively shape both men and women’s gender role socialization. Many times both men and women are unaware of the interaction of macro-societal and micro-interpersonal levels but it is fully operative in negative psychological ways. The outer triangle represents the socio-political context and a way to understand how societal factors contribute to restrictive masculinity ideologies, and GRC that cause emotional and psychological problems, internalized oppression, and societal discrimination and oppression (Pommper, 2022).

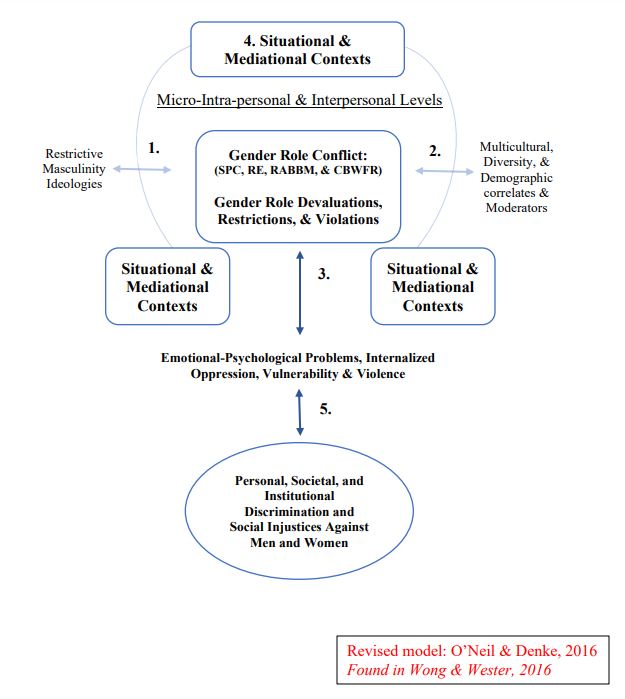

Figure 2 shows a modified version of Figure 1 with the macro-societal factors removed so that just the micro-interpersonal and interpersonal levels of men’s experiences are the main focus. This deletion is not to diminish the importance of the macro-societal oppression but to focus on the intra-personal and interpersonal aspect of GRC thereby fostering research that addresses GRC and men’s real life experiences.

The micro-intrapersonal and interpersonal level of analysis is shown in Figure 2, is connected to three rectangles, all labeled as the situational and mediational contexts. The micro-intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions reflect the emotional-psychological experiences with situational, contextual, multicultural, and gender roles conflict that are shaped by the macro-societal dynamics. These three rectangles can be operationalized by two new research paradigms to be discussed below.

Just below the micro-intrapersonal and interpersonal levels in Figure 1 are the GRC patterns: Success, power, and competition (SPC), restrictive emotionality (RE), restrictive and affectionate behavior between men (RABBM), and conflict between work and family (CBWFR) as well as the personal experiences of GRC in terms of gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations. On the far left, restrictive masculinity ideology is shown related to GRC with a bi-directional arrow (line 1) suggesting that masculinity ideology relates to GRC and vice versa. On the right, the multicultural, diversity, demographic, correlates and moderators are shown and include race, ethnicity, culture, class, sexual orientation, age, religious orientation, and cultural identities and ideologies religion, and other diversity factors. The bi-directional arrows show that these multicultural and demographic correlates/moderators and GRC relate to each other (Line 2). Restrictive masculinity ideologies, multicultural, demographic correlates/moderators and GRC are hypothesized to relate emotional and psychological problems, vulnerability and internalized oppression (lines 3). The situational and mediation contexts shown on three sides of the figure (Number 4) imply that third variables and situational events can play a part in the how GRC contributes to men’s psychological problems. Finally, line 5 implies that men’s emotional psychological problems are directly related to personal, societal, and institutional discrimination and social injustices toward men and women.

The model is one way to address past criticism, conceptualize situational research, and connect GRC to societal discrimination and social justice issues. The critical question is whether empirical research can be completed documenting the numbered relationships (1-5) in Figure 2, specifically, between the situational and mediation contexts (Number 4 in Figure 2) and the other contexts.

Past situational research on GRC has been very limited. Only a few studies have studied situations in their research either as a dependent or mediator variables and the rationales used were understandable but not full blown . Four studies examined whether GRC or RE along with a competitive task related to expression of male aggressive behavior (Cohn, Jakupcak, Seibert, Hildebrant, & Zeichner, 2010; Cohn, Seibert, & Zeichner, 2009; Cohn & Zeichner, 2006; Cohn, Zeichner, & Seibert, 2008). Critical discussions between a married couples and men’s GRC have been studied in terms of the number and intensity of critical comments, displays of hostility, and husband withdrawal (Breiding, Windle & Smith, 2008; Breiding 2004; Windle and Smith, 2009). Only one study has examined how GRC was influenced by a situation that consisted of watching a short video clip containing a humorous display of masculine norms (Jones & Heesacker, 2012). These are the only studies where situational dynamics have been assessed.

Gender role contexts need to be described that allows researchers to develop their research designs that actually tap actual gender role dynamics that are interpersonal (between the man and others) or intrapersonal (within the man). Without contextualizing the situational cues, the gender related intrapersonal dynamics occurring may not conceptualized and creating situational research will be difficult to conceptualize.

Situational Examples

GRC situations ” are defined as any event or interaction that stimulates GRC , distorted gender role schemas, or defensiveness because of threat to one’s masculine identity. Second these situations can also promote healthy responses to gender role interactions. Examples of both positive and negative gender related situations are listed in Table 2. These situations activate a man’s memory, his gender role norms/ rules, schemas and gender knowledge as part of the actual informational processing (See O’Neil & Denke, 2016).

As described below, these gender-related situations can be operationalized by real life scenarios that create situational dynamics that can be tested with contextual research.

Table 2. Gender Related Situations

| Examples of Negative Functional & Micro-Contextual Situations: |

|

| Positive Functional & Micro-contextual Situations: |

|

Both positive and negative situations need to be identified. Using positive situations and assessing positive mediators and outcomes would promote the empirical documentation of how positive and healthy masculinity exists and begin to shape the psychology of men around what is good and noble in men’ lives.

Research Paradigms to Do Situational/Contextual Research

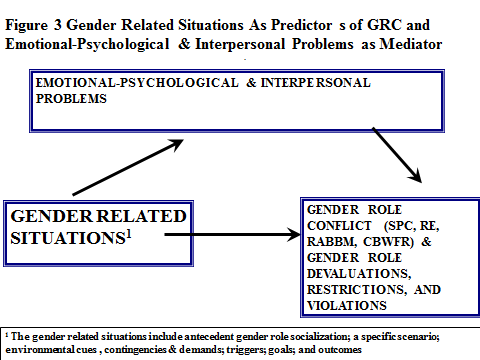

Figure 3 and 4 depict research paradigms where GRC is more than a predictor variable and situational contexts predict GRC as a dependent variable or GRC is a mediator of emotional/psychological problems. The critical question when creating research using Figure 3 and 4 is: What gender related situations cause GRC or how does GRC mediate negative outcomes for men in these situations??

The research question for Figure 3 is how and why do gender related situations relate to emotional-psychological and interpersonal problems with GRC as an outcome in men’s lives. In other words, is GRC an outcome of any negative situational contexts mediated by emotional-psychological problems? For Figure 4, the research question is how does GRC relate to negative gender related situations that cause men’s psychological problems. In other words, does GRC mediate situations in producing negative outcomes for men?

Both figures expand GRC’s role from just being a predictor of men’s problems to both a mediator and outcome of situational contingences that are gender related. This research paradigm suggests many new research questions on how GRC is affected by situational cues in men’s lives. For example, these new models promote situational GRC “from others” and “towards others” to be more completely conceptualized and researched.

First, like all research, studies need to be conceptualized using operationally defined concepts that have theoretical relevance to the psychology of men.

The contextual and situational model in Figure 1 and the two research paradigms have utility when designing situational GRC studies. The model can help researchers theorize about GRC situations and the research paradigms can help create testable hypotheses whether GRC is an outcome variable or mediator variable. The models provide researchers with theoretical foundations to conceptualize their studies. Additional situational parameters need to be generated that expands understanding on how GRC is experienced and caused by others.

Figure 1 and the new GRC assumptions increase our understanding of how situational contexts relates to GRC, masculinity ideology, multicultural and diversity issues, and men’s overall psychological health. The correlational, moderation, and mediation studies reported earlier (See O’Neil, 2008, 2015; O’Neil; & Denke, 2016) provide an empirical foundation for expanded situational research. Unfortunately, the moderation and mediation studies reported do not test for situational dynamics. Predictive paradigms need to be expanded to test situational dynamics in real time for observed outcomes in GRC and assesses how men “do gender” in both experimental and real life settings by identifying triggers in the environment that explain how and when behaviors, attitudes, or internal conditions change or are expressed.

In summary, very little research exists that has examined the situational aspects of GRC because few research paradigms have been developed that can guide this important kind of research. The next steps are to generate more situational research paradigms that can explain the complexity of GRC in men’s lives. The critical questions are how do men learn restricted gender roles, experience GRC in specific situations, under what conditions, with what negative consequences and outcomes. (Addis et al., 2010; Jones & Heesacker, 2012).

The contextual and situational model in Figure 1 and the three research paradigms have utility when designing situational GRC studies. The model can help researchers theorize about GRC situations and the research paradigms can help create testable hypotheses whether GRC is an outcome variable or mediator variable. The models provide researchers with theoretical foundations to conceptualize their studies. Additional situational parameters need to be generated that expands understanding on how GRC is experienced and caused by others.

Unfortunately, very few studies have examined the impact of GRC in a situation or how GRC is influenced by a situation. In order to investigate GRC in a micro-contextual sense, research studies were reviewed that examined GRC in relation to a controlled situation.

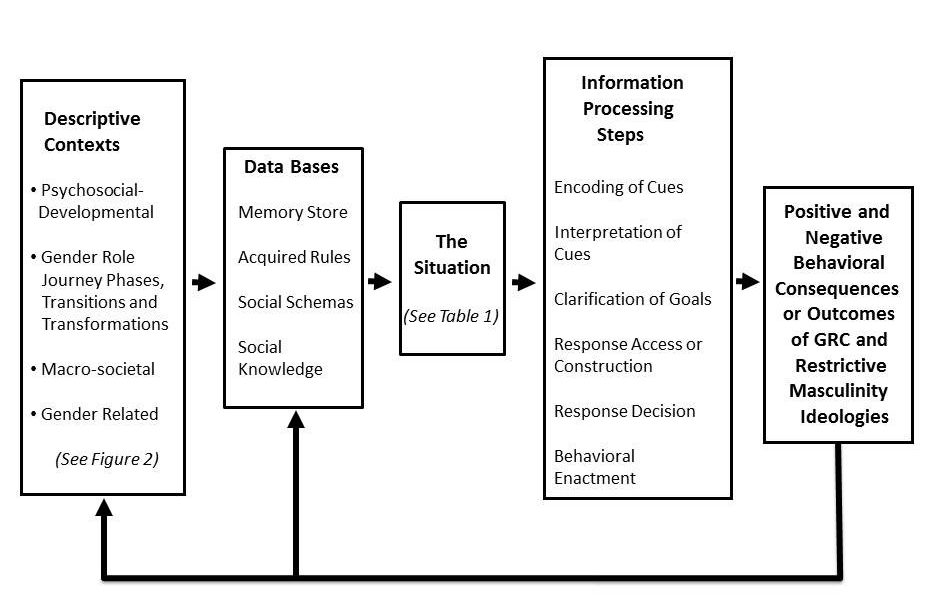

Figure 4. Descriptive, Functional, and Micro-Contextual Model

| 1 I am very grateful to Marty Heesacker for helping me locate the Crick and Dodge model and his advice on model development and micro-contextual aspects of masculinity.

Taken From: O’Neil, J.M. (2015). The contextual paradigms for gender role conflict: Theory, research, and practice. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 41-77. Washington, D.C. APA Books. |

This model addresses the micro-contextual and social learning perspectives of how men’s actions in environments and their gendered interactions with others cause GRC and other psychological problems (Addis et al., 2010; Jones & Heesacker, 2012). This model is designed to promote increased knowledge about the situational aspects of men’s GRC in real time (Addis et al., 2010; Jones & Heesacker, 2012).

Functional and Micro-contextual Aspects of Men’s Behavior

An information processing model was found that captures some of the key elements of assessing men’s actual behaviors and interactions (Crick & Dodge, 1994)1. The model is altered and simplified to serve as an initial template for understanding situational and micro-contextual aspects of men’s actions and behaviors. Readers are referred to the complete manuscript for full details and more in depth accounts of the information processing theory. (Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Crick and Dodge’s model depicts social information-processing mechanism in children’s social adjustment and is adapted here to understand men’s behavior. The model also depicts behavior as having a past “data base” that includes memory store, acquired rules, social schemas, and social knowledge. Their model depicts in a circular fashion six behavioral processes that can be adapted to understand men’s behavior and interactions. The processes include: a) encoding of cues, b) interpretation of cues, c) clarification of cues, d) response access or construction, e) response decision, and f) behavioral enactment.

Figure 3 depicts an adaptation of Crick and Dodge’s information processing conceptualization by integrating their concepts with their descriptive contexts discussed in Figure 2. The information processing perspective of Crick and Dodge is multifaceted and complex compared to my simple adaptation. Nonetheless, the processes described do provide a preliminary example of functional and micro-contextual analyses and with more work could be operationalized in research. On the left of Figure 3 are the descriptive antecedent contexts described earlier in the chapter (psychosocial-developmental, gender role journey phases and transitions, macro-societal, and gender related contexts). The small arrows imply that the descriptive context directly impacts the entire information processing described in the rest of Figure 3. Furthermore, the model shows the positive and negative outcomes leading back to the data bases and the descriptive antecedent contexts in a circular way (See longer arrows). This implies that the consequences of gender related situations contribute to the ongoing shaping of the person and the larger macro-societal system in a circular way.

The descriptive contexts are shown as influencing a man’s “data base” shown in the second rectangle on the left in Figure 3. What this means is that psychosocial developmental aspects of gender roles, the macro-societal dimensions, and the gender related dynamics all become internalized psychologically in the man’s mind. Crick and Dodge define this information as “data bases” that include memories, acquired rules, social schemas, and social knowledge. Each of these data bases have direct implications for the internalization of masculine gender roles and the development of male gender role identity (See Figure 2). Furthermore, the data base categories all relate to the internalization of gender role norms and conflicts (masculinity ideologies and GRC) that are relevant to understanding men’s processes and behavior in situations.

Past Situational Research

Several studies examined whether GRC or RE along with a competitive task related to expression of aggressive behavior (Cohn, Jakupcak, Seibert, Hildebrant, & Zeichner, 2010; Cohn, Seibert, & Zeichner, 2009; Cohn & Zeichner, 2006; Cohn, Zeichner, & Seibert, 2008). For men who experienced negative affect arousal in higher levels, higher levels of GRC predicted of initial, general and extreme aggressive behavior in a competitive situation (Cohn, et al., 2008). While helping men achieve positive, healthy masculinity and resolve their GRC is the larger issue at task, helping men whose negative affect tends to fluctuate highly learn to cope with their negative emotions may be the initial task in lowering aggressive behaviors.

Six studies have found situational dynamics relate to men’s GRC (Cohn, Jakupcak, Seibert, Hildebrant, Zeichner, 2010; Cohn & Ziechner, 2006; Cohn, Seibert, Ziechner, 2009: Cohn, Zeichner, Seibert, 2008; Jones & Heesacker, 2012; Windle & Smith, 2009). The studies have assessed negative affect arousal during a competitive situation (Cohn, et al., 2008), emotional regulation in a competitive environment (Cohn et al, 2010), aggression under competitive circumstance (Cohn & Ziechner, 2006), masculine threat and aggression during a competitive task ( Cohn et al., 2009), husband withdrawal during martial adjustment task (Windle & Smith, 2009), and watching a short humorous video clip (Jones & Heesacker, 2012).

The mediational and situational dimensions of GRC shown in Figure 1 (Number 4) has limited empirical support and should be vigorously pursued by future researchers. New research models to activate more situational research are found late sections of the chapter.

Also, GRC and masculine ideology were both found to be significantly and positively related to displays of aggression in a competitive task (Cohn & Zeichner, 2006). Lower levels of GRC moderated the relationship between masculine ideology and aggressive behavior (Cohn & Zeichner, 2006). Adherence to society’s rigid masculine norms or feeling conflicted about these socialized gender roles may contribute to aggressive behavior of men in competitive circumstances. Men who are highly committed to rigid masculine norms with little to no negative feelings towards their socialized gender roles may be prone to the engaging in aggressive behaviors in a competitive environment.

Restrictive Emotionality may be a key piece of GRC in the situational expressions of aggression. Men displaying aggressive behaviors during a competition task had significantly higher levels of RE than men who did not display aggressive behaviors (Cohn, et al., 2009). While helping men learn about emotions and how to express emotion may play a part in decreasing the number of aggressive acts from men, other complexities exist in the relationship between RE and aggression. Higher levels of RE predicted more instances of aggression in competition for men with higher levels of trait anger and who experienced a recent threat to their masculinity (Cohn, et al., 2009). In addition Cohn et al., 2010 found the relationship between men’s restrictive emotionality and aggressive behavior in a competitive environment was mediated by their inability to cope with or tolerate emotional experiences. Men who feel discomfort in being emotionally vulnerable may have trouble expressing their negative emotions in a positive way, which may default to aggressive behavior. Other emotional dysregulation indices, such as ability to use in goal-directed behaviors, utilize adaptive coping strategies, to label and understand emotions, or to gain knowledge of emotional states, were not found to significantly mediate the relationship between men’s RE and aggression during competition (Cohn, et al., 2010). Considering the complexities in the relationship between RE and aggression, more research needs to be conducted to uncover the situational contributors to male aggression. With alarming statistics on male perpetrators of aggression paired with the complexity of contributors to male aggression more research on situational factors, such as competition, involved in male aggression is needed.

Several researchers have also examined how GRC and a critical discussion between a married couples relates to expression of male behaviors. In a study examining the number and intensity of critical comments made by a husband in the absence of his wife, total criticism, number of highly or lengthy critical comments, and number of highly and lengthy critical comments was significantly related to men’s GRC (Breiding, Windle & Smith, 2008). In a critical discussion between married couples, Breiding (2004) found total GRC, RE, SPC and CBWFR was significantly related to displays of hostility from the husband. Also, Windle and Smith (2009) found men’s expression of withdrawal in a critical marital discussion was significantly correlated with RE and RABBM, but non-significant for total GRCS. Married men may be more likely to be critical of their wife, display hostility towards wife or withdraw during critical discussions due to discomfort in being emotionally vulnerable or overall negative feelings towards socialized gender roles.

The relationship between husbands’ GRC and wives’ martial adjustment was also examined for moderating and mediating factors. Husbands’ expression of withdrawal moderated the relationship between husbands’ GRC and wives martial adjustment (Windle & Smith, 2009). Also, the relationship between husbands’ GRC and wives’ marital adjustment was found to be mediated by the number of critical comments husbands made about their wives, wives ratings of husband criticism and husbands’ rating of own criticism (Breiding et al., 2008) and displays of hostility in discussion of potential changes a spouse should make (Breiding, 2004). The complexities existing in situation of being critical in a martial discussion calls for more research on the role of GRC in being critical.

Furthermore, only one study has examined how GRC was influenced by a situation (Jones & Heesacker, 2012). When examining the impact of watching a short video clip containing a humorous display of masculine norms on GRC, Jones & Heesacker (2012) found men’s GRC was significantly lower than men who did not watch a video clip. Illuminating stereotypical masculine behavior through comical interventions may alleviate men’s GRC and put them in a position to be able to redefine their own gender roles and learn to cope with and resolve gender role conflict they have experienced.

References

Breiding, M. J. (2004). Observed hostility and dominance and mediators of the relationship between husbands’ gender role conflict and wives outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(4), 429-436.

Breiding, M. J., Windle, C. R., & Smith, D. A. (2008). Interspousal criticism: A behavioral mediator between husbands’ gender role conflict and wives’ adjustment. Sex Roles, 59, 880-888.

Cohn, A. M., Jakupcak, M., Seibert, L. A., Hildebrant, T. B., & Zeichner, A. (2010). Role of emotion dysregulation in the association between men’s restrictive emotionality and use of physical aggression. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 11(1), 53-64.

Cohn, A. M., Seibert, A., & Zeichner, A. (2009). Role of restrictive emotionality, trait anger and masculinity threat in men’s perpetration of physical anger. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 10(3), 218-224.

Cohn, A., & Zeichner, A. (2006). Effects of masculine identity and gender role stress on aggression in men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 7(4), 179-190.

Cohn, A. M., Zeichner, A., & Seibert, L. A. (2008). Labile affect as risk factor for aggressive behavior in men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 9(1), 29-39.

Jones, K. D., & Heesacker, M. (2012). Addressing the situations: Some evidence for significant of microcontexts with the gender role conflict construct. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 13(3), 294-307.

Windle, C. R., & Smith, D. A. (2009). Withdrawal moderates the association between husband gender role conflict and wife martial adjustment. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 10(4), 245-260.

Micro Contextual Situational Studies

click the boxes below to view each study

Cohn, A. M., Zeichner, A., & Seibert, L. A. (2008). Labile affect as risk factor for aggressive behavior in men.

Cohn, A. M., Zeichner, A., & Seibert, L. A. (2008). Labile affect as risk factor for aggressive behavior in men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 9(1), 29-39.

Sample: 92 undergrads men 18-22; 85% White, 11% African American, 1% Asian, 1% Hispanic, 1% other

Method:

- GRCS- measured pre task

- PANAS (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule)- assess positive/ negative affect along with anger & hostility; measured pre and post task

- Response Choice Aggression Paradigm- “measures direct physical aggression under laboratory conditions” (32), participants are allowed to administer shocks to “opponent” on scale of 1-10 (told moderate to high pain level), participants shocked after they “lose” (light on console shows what pain level was given to them), participants can administer shocks after opponent loses, fictitious win/ losses based on competitive reaction time task

- General aggression: “mean shock intensity for trails in which the participant administers a shock

- Extreme aggression: “proportion of highest shock available used relative to trials in which any shock was administered

- Initial aggression: “intensity of first shock administered by participants” (32)

Results:

- 77% felt like good measure of their reaction time

- No significant changes in negative affective pre vs. post task

- Negative affect score change significantly correlated with GRCS (r=.24, p<.05)

- GRCS score significantly correlated with aggression (r=.27, p<.05)

- Moderating effects of change in negative affect on relationship between GRC and aggression

- General aggression: “GRCS scores significantly and positively related to aggression at high levels of negative affect change” (34)… non-significant for low levels of negative affect change

- Extreme aggression: “at high levels of negative affect change, GRCS scores were significantly related to extreme aggression”… non-significant for low levels of negative affect change

- Initial aggression “At high levels of negative affect change, GRCS scores were significantly related to initial aggression… non-significant for low levels of negative affect change

Summary: For men who experienced negative affect arousal in higher levels, higher levels of GRC predicted of initial, general and extreme aggressive behavior in a competitive situation.

Implications: The relationship between GRC and aggression is apparent. While helping men resolve their GRC is the larger issue at task, helping men whose negative affect level tends to fluctuate highly learn to cope with their negative emotions may be the initial task in lowering aggressive behaviors. [i.e. men who “fly off the handle” “0 to 100”]

Cohn, A. M., Jakupcak, M., Seibert, L. A., Hildebrant, T. B., & Zeichner, A. (2010). Role of emotion dysregulation in the association between men’s restrictive emotionality and use of physical aggression.

Cohn, A. M., Jakupcak, M., Seibert, L. A., Hildebrant, T. B., & Zeichner, A. (2010). Role of emotion dysregulation in the association between men’s restrictive emotionality and use of physical aggression. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 11(1), 53-64.

Sample: 128 male undergrads 18-25 (104 completed study), 96% single, 80.5% White, 5.7% African American, 8.9% Asian, 1.6% American-Indian/ Alaskan Native, 3.3% other; told to assess personality traits and reaction time

Method:

- RE subscale of GRCS; pre task

- Difficulties with Emotional Regulation Scale: measure emotion dysregulation in subscales of nonacceptance, goal-directed, impulsive, strategies, awareness, clarity; pre task

- Opponent Evaluation Scale: opinion of fictitious opponent

- Response Choice Aggression Paradigm (RCAP): see above

- Mean Shock Intensity

- Shocks given to participants too (see above)

Results:

- 17% administered no shocks; difference in level of RE between shockers and non-shockers

- Relationship between RE and aggression mediated by non-acceptance piece of emotional dysregulation (inability to tolerate or cope with emotional experiences)

Summary: A relationship between men’s restrictive emotionality and aggressive behavior in a competitive environment was mediated by their inability to cope with or tolerate emotional experiences. Other emotional dysregulation indices, such as ability to use in goal-directed behaviors, utilize adaptive coping strategies, to label and understand emotions, or to gain knowledge of emotional states, were not found to significantly mediate the relationship between men’s RE and aggression during competition.

Implications: The mediating relationship between men with RE who lack the ability to tolerate their emotional experiences and physical aggression highlights the importance of future research on contributing factors to male aggression. With alarming statistics on male perpetrators of aggression paired with the complexity of contributors to male aggression prompts a call to action for research on situational factors, such as competition, involved in male aggression.

Cohn, A., & Zeichner, A. (2006). Effects of masculine identity and gender role stress on aggression in men.

Cohn, A., & Zeichner, A. (2006). Effects of masculine identity and gender role stress on aggression in men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 7(4), 179-190.

Sample: 97 undergrad men 18-35, 86% White, 11% African American, 1% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 1% other, told measuring personality traits and reaction time

Method:

- CMNI: conformity to masculine norms inventory; pre task

- GRCS: pre task

- Response Choice Aggression Paradim (RCAP)

- Mean shock intensity

- Mean shock duration

- Proportion of highest shocks

- Flashpoint: # of trials that expire before participant administers first shock

- Flashpoint intensity: intensity of first shock delivered

- Flashpoint duration: duration of first shock delivered

- Shock frequency

- Shocks given to participant too (see above)

Results

- CMNI significantly and positively related to mean shock intensity and proportion of highest shock delivered

- GRCS significantly correlated with flashpoint (negative), flashpoint duration (positive) and shock frequency (positive)

- GRC moderated relationship between CMNI and average intensity of shock, proportion of highest shock, number of trials before participant delivered shock, intensity of first shock for low GRC, shock frequency & shock frequency for low levels of GRC

Summary: GRC and masculine ideology both significantly and positively related to aggression. Lower levels of GRC moderated the relationship between masculine ideology and aggressive behavior.

Implications: Adherence to society’s rigid masculine norms or feeling conflicted about these socialized gender roles may contribute to aggressive behavior of men in competitive circumstances. In addition, men highly committed to rigid masculine norms with little to no negative feelings towards their socialized gender roles may play a role in the demonstration of aggression behaviors from men in a competitive environment.

Cohn, A. M., Jakupcak, M., Seibert, L. A., Hildebrant, T. B., & Zeichner, A. (2010). Role of restrictive emotionality, trait anger and masculinity threat in men’s perpetration of physical anger

Cohn, A. M., Seibert, A., & Zeichner, A. (2009). Role of restrictive emotionality, trait anger and masculinity threat in men’s perpetration of physical anger. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 10(3), 218-224.

Sample: 128 undergrads (103 completed study), 80.5% white, 97.6% single; randomly assigned to threat/ non-threat group

Methods:

- RE subscale of GRCS; pre task

- Anger subscale of Buss Aggression Questionnaire: “disposition toward trait anger”; pre task

- Positive and Negative Affect Schedule- Expanded Form: positive, negative affect & anger/ hostility; before and after receiving feedback

- Response Choice Aggression Paradigm (RCAP)

- Mean Shock Intensity

- Flashpoint: number of trials before participant administered shock

- Shock Frequency

- Shocked back as well (see above)

- “Identity self report measure” to help deceive participants; pre task

- Told either fall in feminine (threat) or masculine (non-threat) identity range; completed PANAS again; then started reaction time shock task

Results:

- Non-significant relationship between RE and trait anger

- Aggressors significantly more RE than non aggressors, anger& hostility was non-significant co-variate of RE

- RE positively correlated shock frequency (aggression) with participants with high trait anger in threat condition

Summary: Men displaying aggressive behaviors in competition task had significantly higher levels of RE than men who did not display aggressive behaviors. Higher levels of RE predicted more instances of aggression for men with higher levels of trait anger and who experienced a threat to their masculinity.

Implications: Considering the non-significant association between RE and disposition toward trait anger along with the moderating effect trait anger and experienced threat toward masculinity had in the RE predicting aggression, more research needs to be conducted on situational contributors to male aggression. It is possible that with men restricting their emotions, endorsement of trait anger and a threat to their masculinity may contribute to the likelihood of them engaging in aggressive behaviors towards others.

Breiding, M. J. (2004). Observed hostility and dominance and mediators of the relationship between husbands’ gender role conflict and wives outcomes.

Breiding, M. J. (2004). Observed hostility and dominance and mediators of the relationship between husbands’ gender role conflict and wives outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(4), 429-436.

Sample: 60 couples, currently married/ cohabiting, mostly white

Methods:

- GRCS: pre marital adjustment task

- Dyadic Adjustment Scale: self report; pre martial adjustment task

- Beck Depression Inventory: self report; pre martial adjustment task

- Observed hostility and dominance scale of Checklist of Interpersonal Transactions Revised: measure husband observed hostility and dominance during marital interaction task; 3 independent raters observed video and rated every 3 minutes for 10-minute interaction

- Randomly assigned to whether husband or wife would be focus of discussion then list 5 things both would agree on to change about that person; if agreed on any element of change- was chosen to talk about; if no agreement- non focus person choose a topic; couple asked to discuss topic for 10 minutes alone (research assistant gave instructions then left the room)

Results:

- Significant association between GRC and decreased martial adjustment in men

- Positive and significant relationship between GRC and depressive symptoms

- Wife martial adjustment and depressive symptoms significantly related to RE, RABBM and SPC.

- GRC, RE, SPC and CBWFR significantly related to observed hostility, but not dominance.

- More observed hostility and dominance when husband was focus of the discussion, only significant more for observed hostility.

- Relationship between Husband GRC and wife marital adjustment mediated by observed hostility.

Summary: Breiding (2004) found that significant relationship between GRC and decreased martial adjustment for men, along with a significant relationship between GRC and depressive symptoms. Wives martial adjustment and depressive symptoms were significantly associated with husbands’ RE, RABBM and SPC. Total GRC, RE, SPC and CBWFR was found to be significantly related to observed hostility from the husband, but non-significant for observed dominance. When husbands were the focus of discussion regarding changes he should make, husbands significantly received higher observed hostility ratings than when the wife was the topic of discussion. Furthermore, observed hostility in discussion of potential changes a spouse should make significantly mediated the relationship between husbands’ GRC and wives marital adjustment.

Implications: The relationship between GRC and expression of hostility indicates the situational expression of hostility may play a role in men’s gender role conflict. Considering the association between husband as focus for potential change and observed hostility, research needs to be conducted on GRC and the situational experience of a critical discussion in relation to expressions of hostility.

Windle, C. R., & Smith, D. A. (2009). Withdrawal moderates the association between husband gender role conflict and wife martial adjustment

Windle, C. R., & Smith, D. A. (2009). Withdrawal moderates the association between husband gender role conflict and wife martial adjustment. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 10(4), 245-260.

Sample: 150 married couples, mostly white, information on length of marriage, age, education and income in article

Method:

- GRCS

- Beck Depression Inventory

- Dyadic Adjustment Scale

- Couples Interaction Rating System for observed demand/ withdrawal behavior

- Videos coded by undergrad/ grad research assistants after viewing entire 10-minute segment

- Randomly selected one partner as focus, automatically focus if met DSM criteria of depression, 5 things to change about focus spouse, if agreement- highest ranked item chosen for discussion topic, if no agreement- non focus spouse chose topic; asked to discuss for 10 minutes alone

Results:

- Husbands’ significantly higher marital adjustment; wives significantly more depressive symptoms

- Husbands significantly higher levels withdraw and higher levels of withdrawal when they were focus; Husbands significantly more demanding when wives were focus; Wives significantly higher levels of demand; Wives significantly more demanding when husband was focus of task; Wives significantly higher levels of withdrawal when they were the focus of the task

- Significant relationship between GRC and martial adjustment in men & GRC with dysphoria (as measured by what?)

- Significant relationship between husband withdrawal and wife demand

- GRCS not significantly correlated with husbands’ withdrawal; withdrawal associated with RE and RABBM

- GRCS correlated with wives depressive symptoms & RE/ RABBM with wives martial adjustment

- No moderation of discussion topic in relationship between GRCS and withdrawal for men

- Husband withdrawal moderated relationship between GRCS and wives martial adjustment

- No moderation for husband withdrawal in relationship between GRCS and wives depressive

- RE significantly associated with husband withdrawal even when controlling for wives’ demand

Summary: Men’s expression of withdrawal in a martial adjustment task was significantly correlated with RE and RABBM, but non-significant for total GRCS. This relationship was not found to be moderated by which spouse was the topic for aspects of potential change discussion. The relationship between RE and husbands’ withdrawal remained significant when controlling for levels of wives’ demand in martial adjustment task. In addition, the relationship between GRCS and wives martial adjustment was moderated by husbands’ expression of withdrawal in martial adjustment task.

Implications: Married men may be more likely to withdraw during critical discussions of either spouse due to discomfort in being emotionally vulnerable. In addition, the expression of withdrawal embedded in the situation of a critical discussion of either spouse contributes to the relationship between men’s GRC and wives’ martial adjustment.

Breiding, M. J., Windle, C. R., & Smith, D. A. (2008). Interspousal criticism: A behavioral mediator between husbands’ gender role conflict and wives’ adjustment

Breiding, M. J., Windle, C. R., & Smith, D. A. (2008). Interspousal criticism: A behavioral mediator between husbands’ gender role conflict and wives’ adjustment. Sex Roles, 59, 880-888.

Sample: 72 cohabiting married couples for at least 1.5 years, mostly white

Method:

- GRCS

- Dyadic Adjustment Scale: martial adjustment

- Beck Depression Inventory

- Perceived Criticism Scale: measures perceived criticism from and towards spouse

- Five Minute Speech Sample: Behavioral criticism (dislike, disapproval, resentment) and by intensity (brief & low, high or lengthy, high & lengthy)

- Coded videotapes, 4 coders per tape

- Was speech sample collected in front of or without spouse?

Results:

- GRCS and SPC associated with spousal criticism rated by self and by wife

- GRCS significantly related to total number of critical comments made

- GRCS and SPC significantly related to number of highly critical or lengthy and highly critical and lengthy criticisms towards spouse.

- RE significantly associated with wife reported criticism, number of critical comments and number of level 2 and 3 intensity

- RABBM significantly associated with wife reported criticism and number of level 3 comments

- CBWFR significantly associated with number of level 3 comments

- wives rating of husband criticism and husband rating of own criticism mediated the relationship between GRC and wives depressive symptoms

- Wives rating of husband criticism, husband rating of own criticism and husbands number of critical comments mediated the relationship between GRC and wives’ martial adjustment.

Summary: Total criticism, number of highly or lengthy critical comments, and number of highly and lengthy critical comment made about wives was significantly related to men’s GRC. Significant patterns in total number or total number critical comments of different levels of intensity emerged for each of the GRCS subscales as well. The number of critical comments husbands made about their wives, along with wives ratings of husband criticism and husbands’ rating of own criticism, mediated the relationship between GRC and wives’ martial adjustment.

Implications: The situation of a speaking critically about their wife, whether total number of critical comments made or intensity level of critical comments, may play a role in men’s experience of gender role conflict.

Jones, K. D., & Heesacker, M. (2012). Addressing the situations: Some evidence for significant of microcontexts with the gender role conflict construct

Jones, K. D., & Heesacker, M. (2012). Addressing the situations: Some evidence for significant of microcontexts with the gender role conflict construct. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 13(3), 294-307.

Sample: 158 men 18-23, mostly freshman & sophomore, mostly white, mostly straight

Methods:

- Video clips with comedy about normative masculine behavior

- Watched video and then rated video, took GRCS and measure of self concept clarity (SCC) online

- Control group: no video clips, just took GRCS and self-concept clarity

- Treatment group: watched one of six video clips on masculine behavior then took GRCS and SCC (primes condition)

Results:

- Self-concept clarity and watching video clip accounted for 17% variance in total GRCS

- Participants watching comical video clip on normative masculine behavior had significantly lower GRCS scores than control group.

- Self-concept clarity did not moderate the relationship between GRCS and video clip condition

- SCC predicted GRCS (higher self concept clarity à higher GRCS)

- SCC predicted RE and CBWFR scores

Summary: The experience of watching a short video clip containing humorous display of masculine norms to potentially expose gender stereotypes was significantly related to lower GRC compared with GRC of men who did not watch a video clip.

Implications: Illuminating stereotypical masculine behavior through comical interventions may alleviate men’s GRC and put them in a position to be able to redefine their own gender roles and learn to cope with and resolve gender role conflict they have experienced.