- Introduction to Gender Role Conflict (GRC) Program

- Overall Information about GRC- Books, Summaries, & History

- Gender Role Conflict Theory, Models, and Contexts

- Recently Published GRC Studies & Dissertations

- Published Journal Studies on GRC

- Dissertations Completed on GRC

- Symposia & Research Studies Presented at APA 1980-2015

- International Published Studies & Dissertations on GRC

- Diversity, Intersectionality, & Multicultural Published Studies

- Psychometrics of the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS)

- Factor Structure

- Confirmatory Factor Analyses

- Internal Consistency Reliability Data

- Internal Consistency & Reliability for 20 Diverse Samples

- Convergent & Divergent Validity of the GRCS Samples

- Normative Data on Diverse Men

- Classification of Dependent Variables & Constructs

- Authors, Samples & Measures with 200 GRC Guides

- Correlational, Moderators, and Mediator Variables Related to GRC

- GRC Research Hypotheses, Questions, and Contexts To be Explored

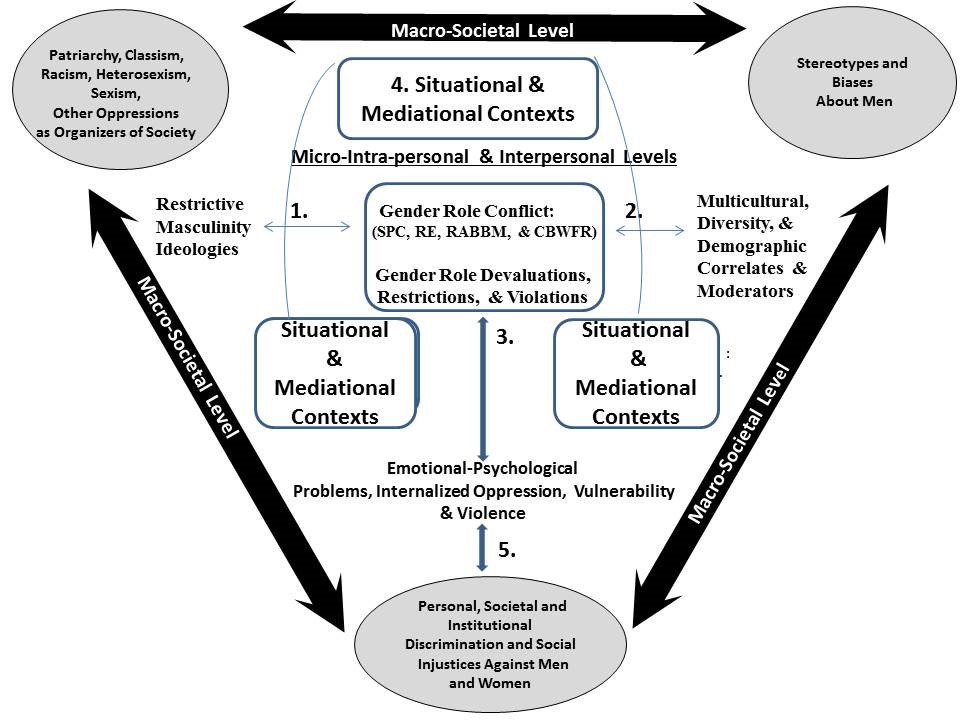

- Situational GRC Research Models

- 7 Research Questions/ Hypotheses on GRC & Empirical Evidence

- Important Cluster Categories of GRC Research References

- Research Models Assessing GRC and Hypotheses To Be Tested

- GRC Empirical Research Summary Publications

- Published Critiques of the GRCS & GRC Theory

- Clinically Focused Models, Journal Studies, Dissertations

- Psychoeducation Interventions with GRC

- Gender Role Journey Theory, Therapy, & Research

- Receiving Different Forms of the GRCS

- Receiving International Translations of the GRC

- Teaching the Psychology of Men Resource Webpage

- Video Lectures On The Gender Role Journey Curriculum & Additional Information

Theoretically driven research studies can best contribute to our knowledge about men and stimulate new areas of GRC research.

The references in this section provide the published GRC theory including GRC definitions, domains, experiences, and situational contexts. Conceptual models describe how GRC can be understood at both a macro-societal and micro-interpersonal levels, including developmental, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and multicultural/social justice contexts.

Topic Areas in this File

- References for Published GRC theory

- Brief GRC definitions, topics, and contexts

- Expanded explanations of theoretical topics, domains, and situational contexts of GRC

- Early conceptualizations of GRC 1970s’ & early 1980s’

- The Counseling Psychologist Model 1981

- Early Model and assumptions about GRC

- Diagnostic schema explaining men’s personal experience of GRC

- Abuses of power against women, sexism, GRC, psychological violence

- Conceptual paradigm to understand men’s and women’s gender role transitions and conflict over the lifespan

- Conceptual paradigm to understand men’s violence against women’s from a gender role conflict and gender role socialization perspective

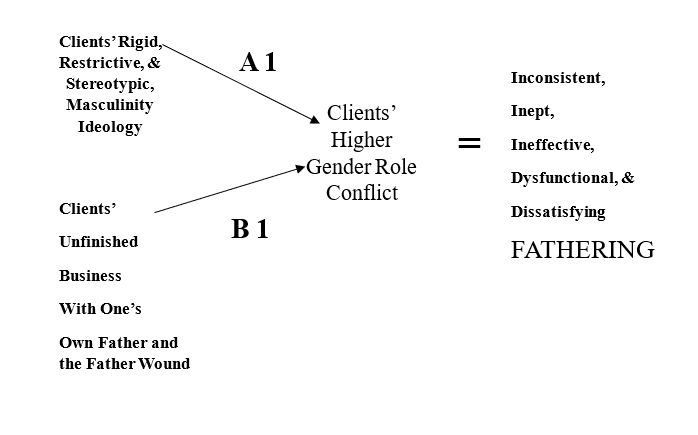

- Figure 1 GRC and fathering contexts

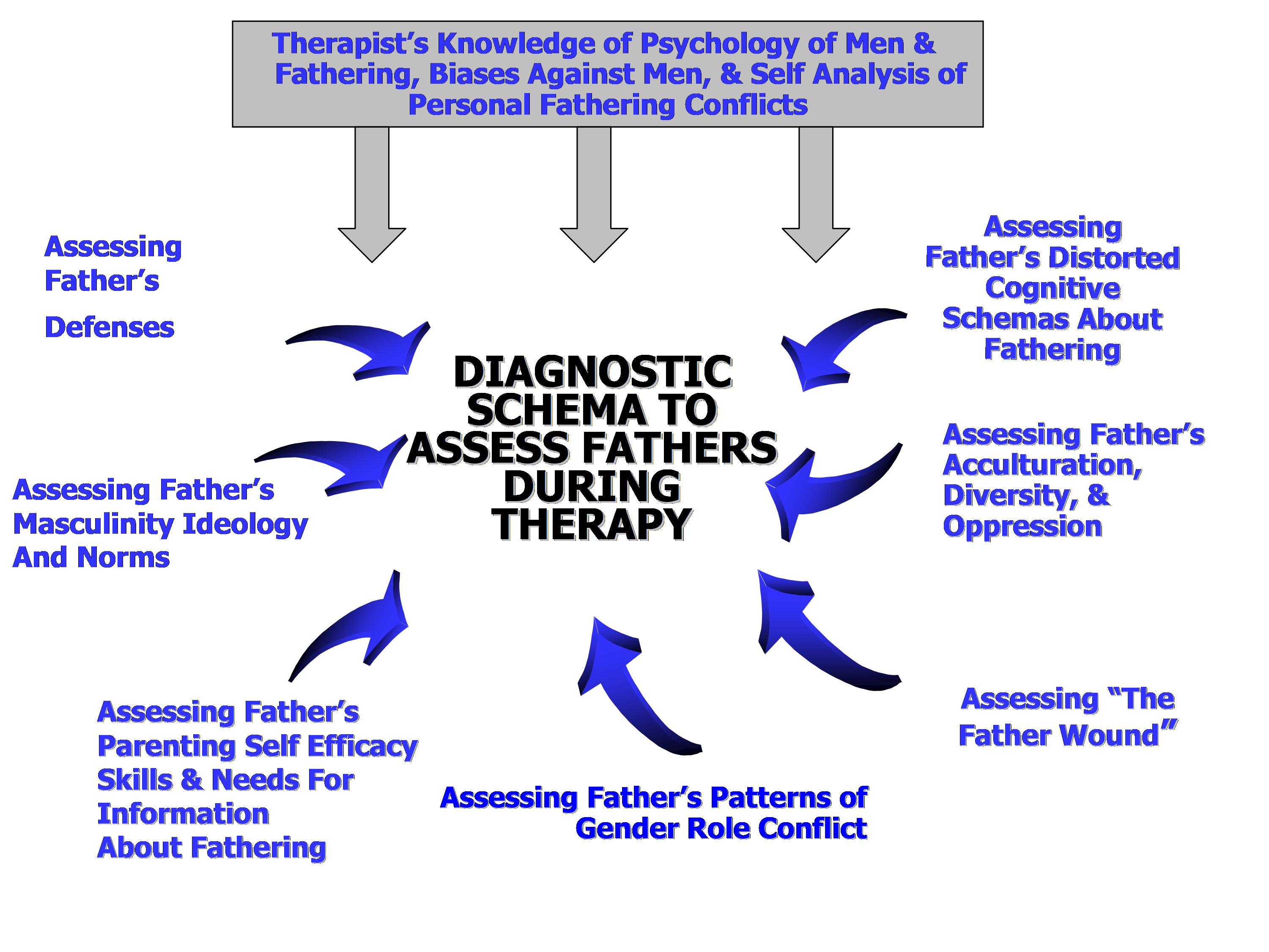

- Diagnostic schema to assess fathers during therapy

- Table 3 New theoretical assumptions about men’s GRC

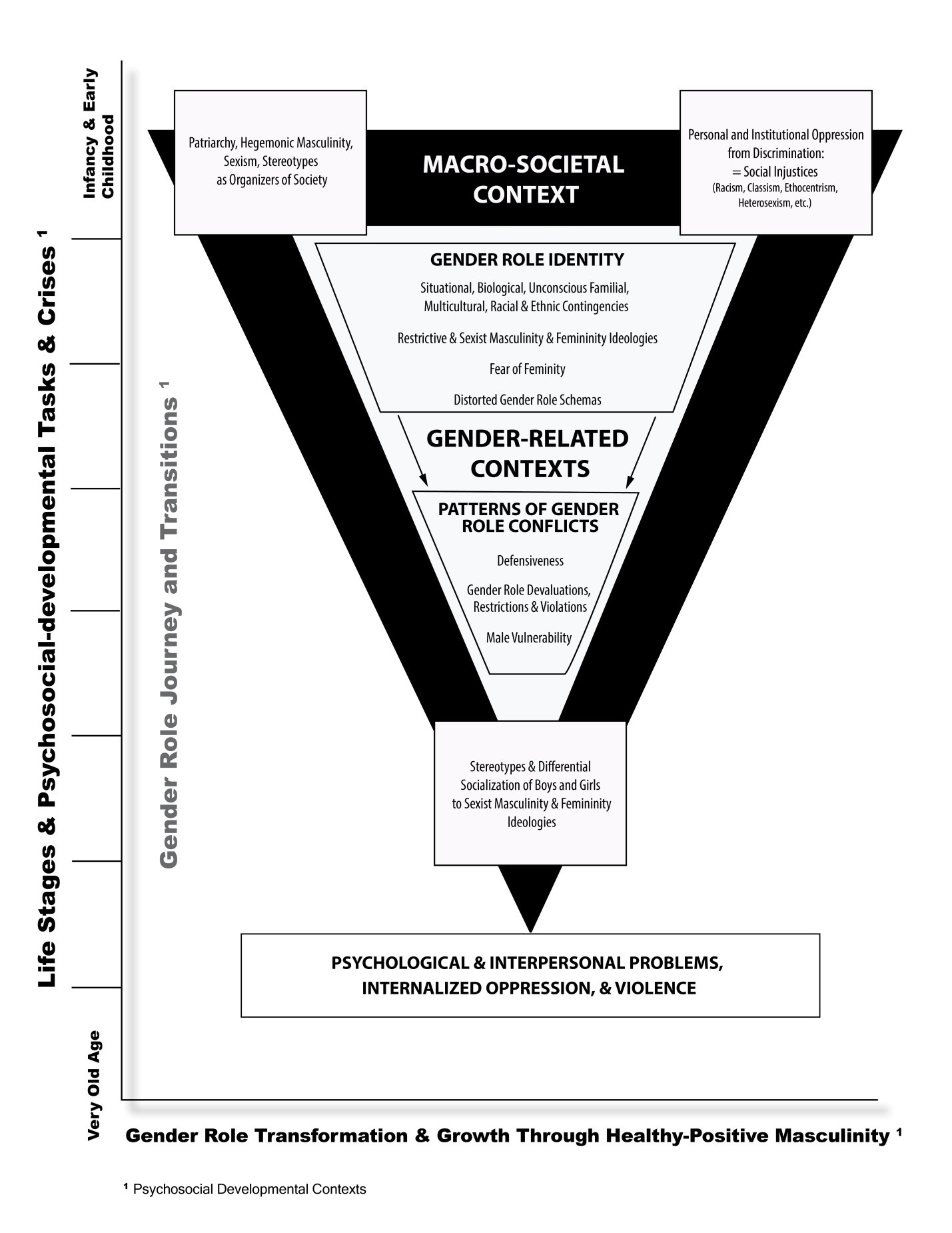

- Descriptive contextual model of men’s gender role socialization and GRC

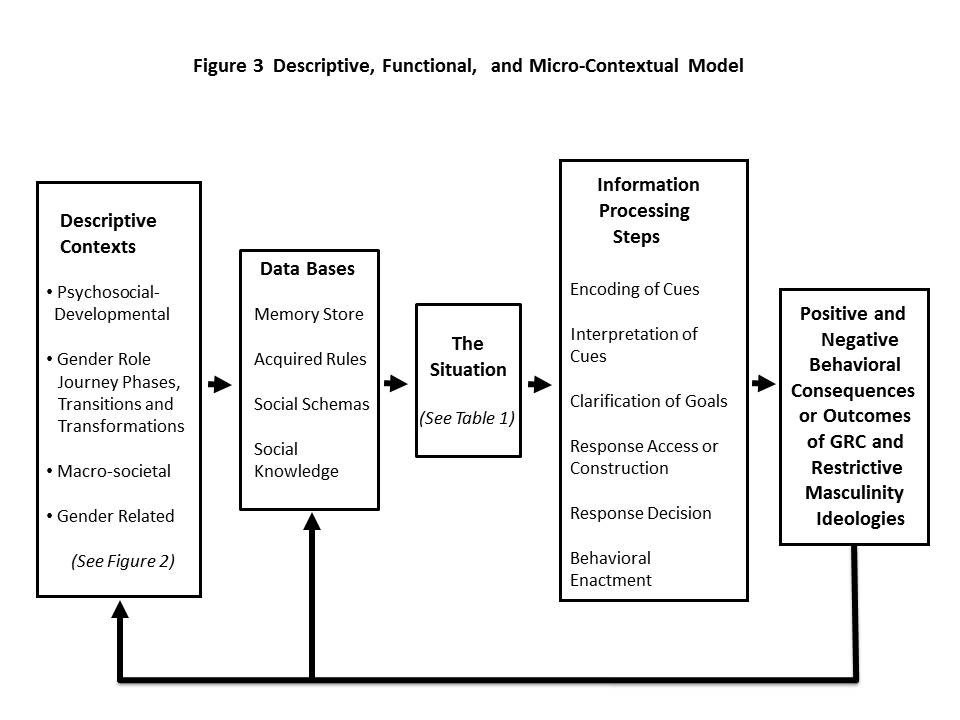

- Descriptive, functional, & micro-contextual model

- Developmental model describing gender role transitions across the life cycle

- Theoretical assumptions about developmental masculinity, gender role conflict, gender role transitions, & psychosocial growth

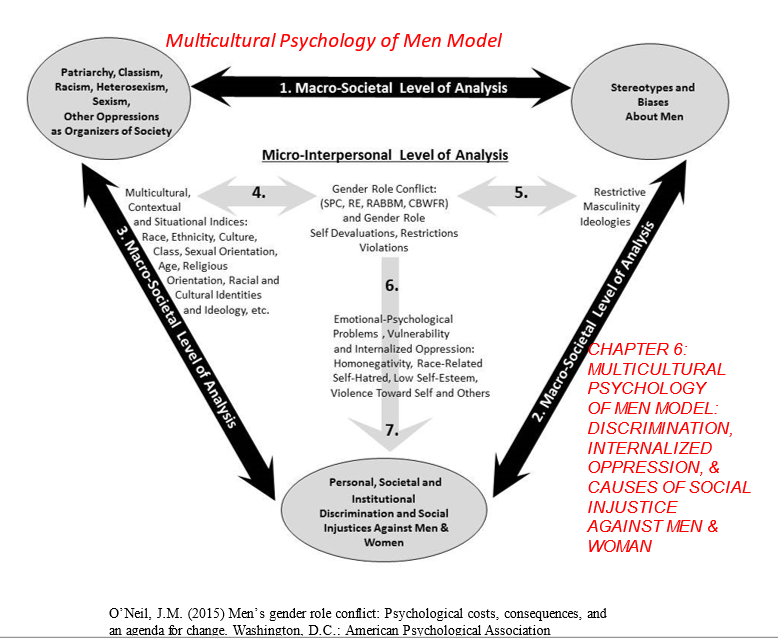

- A multicultural psychology of men model

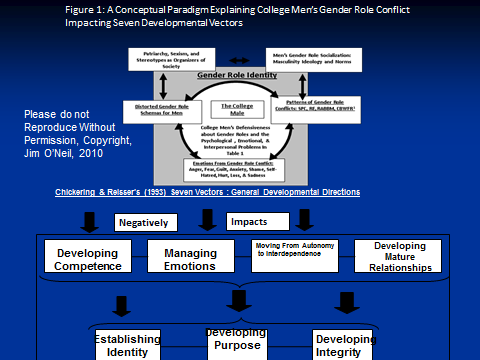

- Conceptual paradigm to understand male college students: Integrating the psychology of men and student development theory

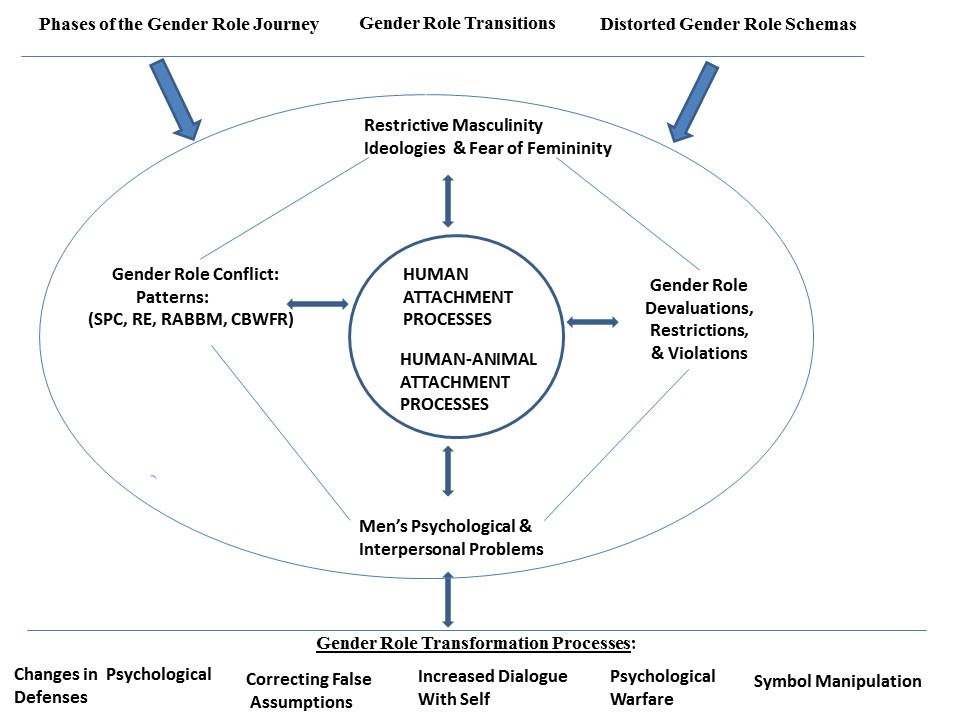

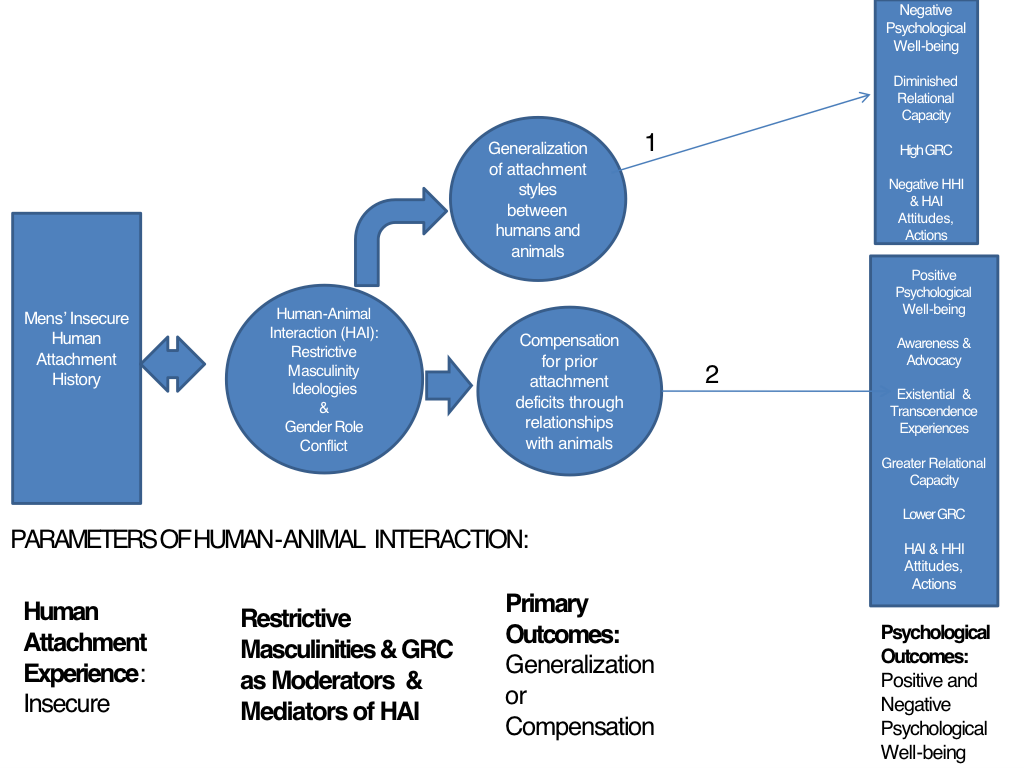

- A model to understand men men’s human and animal attachment in the context of gender role conflict

- A model expanding our understanding of the animal-human bond

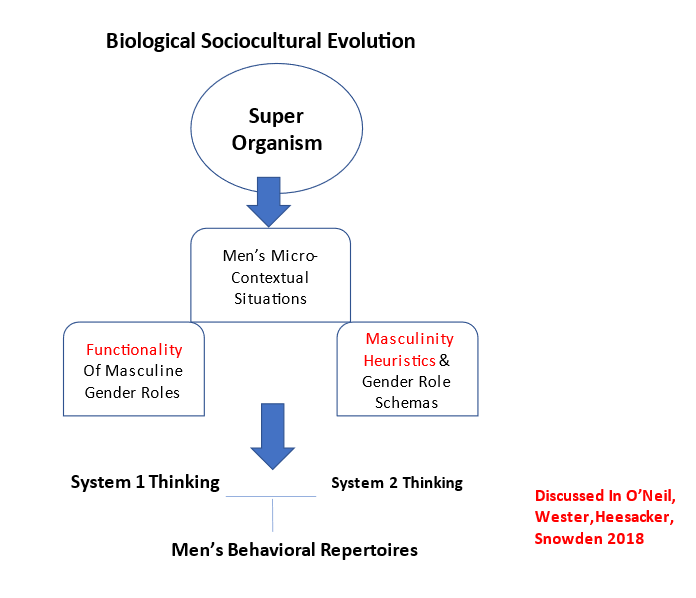

- Biologic, sociocultural, & system thinking model

Publications on GRC Theory

O'Neil, J. M. (1981). Male sex-role conflicts, sexism, and masculinity: Implications for men, women, and the counseling psychologist. The Counseling Psychologist, 9, 61-80.

O'Neil, J. M. (1981). Patterns of gender role conflict and strain: Sexism and fear of femininity in men's lives. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 60, 203-210.

O'Neil, J. M. (1982). Gender role conflict and strain in men's lives: Implications for psychiatrists, psychologists, and other human service providers. In K. Solomon & N. Levy (Eds.), Men in transition: Theory and therapy. New York: Plenum Publishing Company.

O'Neil, J. M., & Egan, J. (1992). Abuses of power against women: Sexism, gender role conflict, and psychological violence. In E. Cook (Ed.) Women, relationships, and power: Implications for, counseling. Alexandria, VA: ACA Press

O’Neil, J. M. & Nadeau, R.A. (1999). Men’s gender role conflict, defense mechanism, and self-protective defensive strategies: Explaining men’s violence against women from a gender role socialization perspective. In M. Harway & J.

Harway, M. & O’Neil, J.M. (Eds.) (1999). What Causes Men’s Violence? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

O’Neil, J.M. (2008). Summarizing twenty-five years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale: New research paradigms and clinical implications. The Counseling Psychologist. 36, 358-445.

O’Neil, J.M. & Crapser, B. (2011). Using the psychology of men and gender role conflict theory to promote comprehensive service delivery for college men; A call to action. In J. Laker & T. Davis (Eds.) Masculinities in Higher education: Theoretical and Practical Considerations, New York: Routeledge Publishers.

O’Neil, J.M. (2015) Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association

O’Neil, J.M. (2015). A developmental model of masculinity: Gender role transitions and men’s psychosocial growth. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 79-93. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

O’Neil, J.M. (2015). A multicultural psychology of men model: Reviewing research on diverse men’s gender role conflict. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 95-119. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

O’Neil, J.M. (2015). New contextual paradigms for gender role conflict: Theory, research, and practice. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 41-77. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

O’Neil, J.M. & Denke, R. (2015). An Empirical review of the gender role conflict research: New conceptual models and research paradigms. In J. Wong and S. Wester (Eds.) APA Handbook of the Psychology of Men and Masculinities. (pp 51-80), Washington, D.C.: APA Books.

O’Neil, J.M. (2015). Theoretical and empirical justification for psychoeducational programming for boys and men. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 301-312. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

Blazina, C., O’Neil, J.M., Denke, R. (2016). A new understanding of man best friend: A proposed contextual model for the exploration of the human-animal bond interactions among insecurely attached males. In C. Blazina, & L.R. Kogan (Eds.) Men and their dogs: A new understanding of man’s best friend (pp. 47-71). New York: Springer.

O’Neil, J.M. Denke, R. & Blainza, C. (2016). Gender role conflict theory, research, and practice: Implications for understanding the human-animal bond. In C. Blazina, &

L.R. KIogan (Eds.) Men and their dogs: A new understanding of man’s best friend (pp. 11-45). New York: Springer.

O’Neil, J.M. Heescker, M. Wester, S. & Snowden, S (2017) Masculinity as a heuristic: Gender role conflict theory, superorganism, and system-level thinking. In R. Levant & J. Wong (Ed.) The psychology of men and masculinities (pp.75-103). Washington, D.C.: APA Books.

Brief Definitions, Theoretical Topics, Domains, and Situational Contexts of Gender Role Conflict

Table 1: Brief Definitions, Theoretical Topics, Domains, and Situational Contexts of Gender Role Conflict

|

Gender role conflict is a psychological state in which socialized gender roles have negative consequences on the person or others. Gender role conflict occurs when rigid, sexist, or restrictive gender roles result in personal restrictions, devaluations, or violations of others and self. |

|||||

| Theoretical Topics Related To Gender Role Conflict Theory | Domains of Gender Role Conflict (GRC): | Situational Contexts of GRC: | Interpersonal/Intrapersonal Context of GRC: | ||

| 1.Masculinity & Femininity Ideologies

2. Gender Role Conflict (GRC) Patterns (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) 3. Gender Role Devaluations, Restrictions, & Violations 4. Gender Role Transitions 5. Gender Role Schemas 6. Distorted Gender Role Schemas 7. Gender Role Journey Phases 8. Gender Role Deconstruction Processes 9. Gender Role Transformational Process 10. Political, Social, Transnational, Social Injustices With GRC |

Cognitive

Emotional/Affective Behavioral Unconscious |

GRC Within the Man

GRC Expressed Towards Others GRC Experienced From Others GRC Experienced During Gender Role Transitions |

Gender Role Devaluations

Gender Role Restrictions Gender Role Violations |

||

Expanded Explanations of Theoretical Topics, Domains, and Situational Contexts of Gender Role Conflict

The early GRC models created in the 1970s’ and 1980s’ are presented in this file as well as the most recent models. The evolution of the ideas over the decades is detailed by the 14 models that represent GRC contexts including:

- Patterns of men’s GRC

- Abuses of power against women

- Psychological violence against women and men

- Men’s violence against women

- Developmental/psychosocial dimensions

- Diversity/multicultural, discrimination, social injustice issues

- Fathering

- Descriptive contextual dimensions

- Descriptive/functional/ micro-contextual dimensions

- College student/student development theory

- Human attachment

- Human animal bond

- Biologic/sociocultural/system thinking

These models are described in detail using narratives from past publication.

Why present these models? They represent my evolving thoughts over the years on GRC; starting with simplicity and ending with the complexity of how restrictive gender roles hurt people. The models convey ideas that moved me and were useful in explaining GRC across many studies.

Collectively, the models depict how GRC is a conscious, unconscious, developmental, and psychosocial concept that relates to bonding and attachment dynamics but also to abuse, discrimination, and violence, and social injustice on both the macro-societal and micro-interpersonal levels.

The models and references may be useful to anyone wanting to theorize about how GRC relates to men’s intrapsychic, intrapersonal, interpersonal and situational functioning.

Three video presentations summarize both the GRC and Gender Role Journey theories. The first video provides a general overview of GRC theory and the second one provides the most recent theory from O’Neil (2015). The third video discusses how GRC relates to psychosocial theory and developmental aspects of masculinity over the lifespan.

Click below to view the expanded explanations

Videos on Gender Role Conflict Theory & Psychosocial Theory

Theoretical, developmental & concepts models

3)

Integrating psychosocial theory with gender roles & Gender Role Theory

Definition of GRC

The definition of GRC has evolved from a series of theoretical and research manuscripts produced over the past 35 years (O’Neil, 1981a, 1981b, 1982; 1990; 2008b; O’Neil, et al., 1986; O’Neil et al., 1995; O’Neil & Egan, 1993; O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). GRC is defined as a psychological state in which socialized gender roles have negative consequences for the person or others. It occurs when rigid, sexist, or restrictive gender roles result in personal restriction, devaluation, or violation of others or oneself (O’Neil, 2008). The ultimate outcome of this kind of conflict is the restriction of the human potential of the person experiencing it or a restriction of another person’s potential. GRC has been operationally defined by four psychological domains, three situational contexts, and three personal and interpersonal experiences. These represent the complexity of gender role conflict in people’s lives and are described below.

The Four Psychological Domains of Gender Role Conflict

The psychological domains of GRC imply problems that occur at four overlapping and complex levels—cognitive, emotional (affective), behavioral, and unconscious—and are caused by restrictive gender roles learned in sexist and patriarchal societies.

The cognitive aspect of GRC pertains to thoughts and questions about gender roles, the understanding of which varies based on the developmental level of the boy or man. Dualistic thinkers experience gender roles differently than men with more cognitive complexity. Thinking that one does not meet expected masculine norms or can’t compete can cause discrepancy strain (Pleck, 1995).

The affective domain is how we feel about gender roles, including the degree of comfort or conflict we have living out our gender role identities. Negative emotions can lead to dysfunction, strain, and GRC (O’Neil, 2008b).

Behavioral aspects of GRC include ways we respond to and interact with others and ourselves that produce negative intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes. Discrimination against men and women based on sexist assumptions are examples of how GRC can be expressed behaviorally.

Finally, unconscious GRC encompasses thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to conflicts with gender roles that are beyond our awareness. Early psychoanalytical theorists—such as Freud, Jung, Adler, and Horney—who discussed unconscious conflict with gender roles were, in many ways, referring to GRC.

Situational Contexts of Gender Role Conflict

Previously, GRC was conceptualized as occurring in four general contexts (or categories) that gave the construct a simple explanation and form. These contexts were defined as GRC within the man (intrapersonal); GRC expressed toward others (interpersonal); GRC experienced from others (also interpersonal); and GRC during gender role transitions.

GRC in an intrapersonal context is a man’s experience of negative emotions and thoughts when experiencing gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations. These private and many times unconscious dynamics are discussed in more detail below. GRC expressed toward others occurs when the man’s gender role problems cause him to devalue, restrict, or violate someone else, for example, telling sexist jokes or committing sexual harassment. GRC from others occurs when someone devalues, restricts, or violates another person who deviates from or conforms to masculinity ideology and norms. Finally, GRC occurs during gender role transitions that are part of psychosocial development.

Gender Role Conflict Experiences: Devaluations, Restrictions, and Violations

The first of the three experiences of GRC is gender role devaluations. Such devaluations are negative critiques of oneself or others when conforming to, deviating from, or violating stereotypical gender role norms of masculinity ideology. They result in a lessening of status, stature, and self-esteem, possibly leading to shame, fear, and anger that may be turned inward and, in turn, cause depression and isolation. Men can devalue themselves, be devalued by others, or devalue someone else.

When a man cannot achieve the expected masculine norms emanating from masculinity ideologies, he may devalue and blame himself. Self-devaluations may, for example, occur when a man fails to meet his expectations for success at work, when he cannot provide for his family, or when he cannot be an effective father or spouse because of work overload, stress, and exhaustion. Other devaluations may occur as the result of lost career dreams, unemployment, traumas, divorce, and decreased sexual stamina.

Devaluations from others, particularly competitors, parents, or family members, can be particularly painful and can trigger defensiveness, withdrawal, and sometimes even violence. Examples of being devalued by others include being bullied or subjected to emasculating remarks that imply the man is a loser, a failure, or somehow inadequate. Men may devalue others when they do not meet or they deviate from expected masculine and feminine norms. Gay men and straight women can be targets of devaluations because they deviate from the stereotypes of, respectively, masculinity and femininity. Gender role devaluations can be salient activators of men’s emotional and interpersonal problems.

The second of the three personal and interpersonal experiences is gender role restriction, which implies that GRC confines oneself or others to stereotypical and restrictive norms of masculinity ideology and expected gender roles. Gender role restrictions also result in attempts to control people’s behavior, limit their potential, and decrease human freedom. They occur when masculine and feminine norms prohibit flexibility in work situations and negatively affect family and interpersonal relationships. Such restrictions narrow options and deny people’s needs, and they can result in manipulation and abuses of power. The cost of restricting oneself or others is feelings of loss, guilt, anger, and powerlessness. As with devaluation, men can restrict themselves, be restricted by others, or restrict someone else. Men’s restriction of their own emotions, self-disclosure, and overall communication limits behavioral flexibility and adaptability to life’s unpredictable events. They may, for instance, restrict themselves by devoting their primary energies to work at the expense of their family and parenting roles, which may reduce intimacy, cause work overload, and leave little room for relaxation and a healthy lifestyle. Rigid gender role norms may be forced on others by demanding they conform to one’s own masculinity or femininity ideology, sometimes subjecting them to excessive control, manipulations, criticism, and even emotional abuse.

Gender role violations represent the most severe kind of GRC. They occur when people harm themselves, harm others, or are harmed by others because of destructive gender role norms of masculinity ideology. To be violated means to be victimized and abused, resulting in emotional and physical pain and, sometimes, gender role trauma strain, which can in turn result in severe, negative outcomes in terms of psychological functioning. Men violate themselves by subjecting themselves to overwork, excessive stress, dangerous risks, and abuse of substances to dull painful emotions and life events. Unexpressed emotions like fear, anger, and shame can be internalized, which can cause chronic depression, self-hatred, isolation, serious health problems, and, in some cases, suicide. Gender role violations of others include discriminatory behavior toward women, sexual harassment, homophobic and anti-gay attitudes, emotional abuse, and even sexual and physical assault, all of which stem from stereotypical attitudes about gender roles. Men are violated by others through physical violence, molestations, unfair custody decisions, unjust corporate downsizing, and exposure to dangerous work settings that cause serious injuries. While men’s violation of others is commonly shown or reported in the media, how gender roles contribute to its occurrence is rarely explained. In sum, gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations are the personal and interpersonal experience of GRC and are critical to understanding how men become conflicted with their gender roles.

Synthesis of Contexts and Assumptions Related to GRC and the Psychology of Men

Examples of Macro-Societal Contexts:

Patriarchy; hegemonic masculinity; societal sexism; stereotypes and biases against men; societal discrimination; personal and institutional oppression (racism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, etc.); social injustice; stereotyping about the socialization of boys and girls; differential socialization of boys and girls to sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies; and policy changes to promote change.

Assumptions:

- Macro-societal oppression is an organizer of society and include patriarchy, classism, racism, ageism, heterosexism, and other unjust discrimination that negatively affect men, women, and children.

- Macro-societal contexts negatively restricts male gender role socialization and include patriarchy, sexism, restrictive stereotypes, oppression and social injustices, and the differential socialization of boys and girls to sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies.

- Stereotypes and biases about men cause discrimination, GRC, oppression, and social injustices.

- The multicultural psychology of men studies the psychological costs of the macro-societal oppression that emanates from restrictive masculinity ideologies and GRC.

- Stereotypes and biases about men cause discrimination, GRC, oppression, and social injustices.

- A macro-societal analysis of men’s oppression explains how GRC and masculinity ideologies predict, moderate, mediate, and causes psychological problems, discrimination, and social injustices in men’s lives.

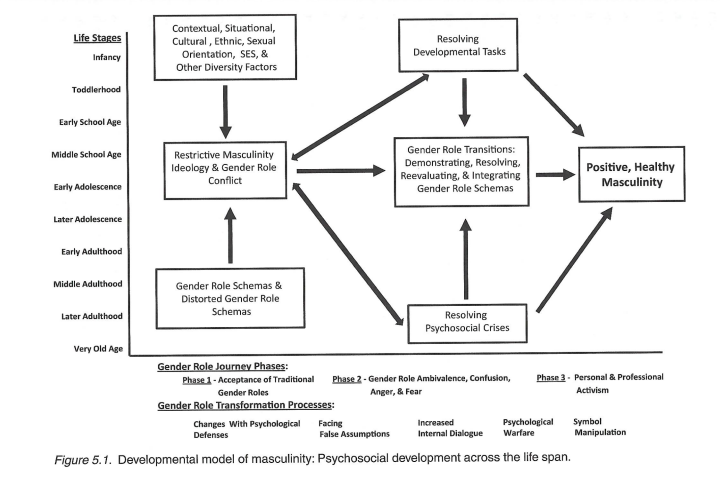

Examples of Psychosocial Developmental Contexts

Developmental tasks; psychosocial crises; demonstrating, resolving, re-evaluating, and integrating masculinity; phases of the gender role journey; gender role schemas; distorted gender role schemas; gender role transformation and growth; healthy and positive masculinity.

Assumptions:

- Gender role conflict and gender role transitions exist throughout the life cycle.

- Gender role development, transitions, and transformations are experienced while mastering the developmental tasks and psychosocial crises over the lifespan.

- Journeying with gender roles over the lifespan and managing gender role transitions are part of seeking positive and healthy masculinity.

- During the life stages, boys and men have varying degrees of restrictive masculinity ideology and GRC that affects psychosocial development of that developmental period.

- Numerous contextual, cultural, and situational factors affect how masculinity ideology and GRC impact psychosocial growth including mastering developmental tasks and psychosocial growth.

- Gender role transitions are necessary to master the developmental tasks and resolve the psychosocial crises.

- Mastering the developmental tasks and resolving the psychosocial crises require changes in a man’s gender role values and self-assumptions.

- Resolving gender role transitions related to developmental tasks and psychosocial crises involves demonstrating, resolving, redefining, and integrating gender role schemas related to masculinity and femininity ideologies.

- Restrictive masculinity ideology and the patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, & CBWFR) may limit behavioral and emotional flexibility and interfere with the developmental tasks and the resolution of the psychosocial crises.

- Efforts to master the developmental tasks and resolve psychosocial crises can cause GRC.

- Distorted gender role schemas about masculinity and femininity may need correction to effectively resolve developmental tasks and the psychosocial crises.

- Fear of femininity and homophobia can interfere with effectively managing gender role transitions and resolving developmental tasks and psychosocial crises.

- Optimal development and positive masculinity are when the developmental tasks and psychosocial crises are resolved and gender role transitions have occurred, meaning that the changed self- assumptions about gender roles facilitate rather than delay further development.

- Journeying with one’s gender roles can facilitate gender role transitions and includes recognizing the costs of gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- The transformation process of journeying with gender roles includes : a) changing psychological defenses, b) facing false assumptions, c) increasing internal dialogue about self, d) managing internal psychological warfare, and e) symbol manipulation.

Examples of Multicultural and Situational Contexts

Race; sex; class; socio-economic status; biology, age; unconsciousness; stage of life; ethnicity; cultural values; nationality; religious orientation; physical disability; sexual orientation; sexual identity; acculturation; oppression from discrimination; internalized oppression; family interaction patterns; being a victim; being unemployed, being homeless; being violent.

Assumptions:

- The multicultural psychology of men identifies the commonalities and differences between men (i.e. diversity)

- Situational, biological, unconscious, familial, multicultural, racial, and ethnic contingencies shape gender role identity in both positive and negative ways.

- At the micro-interpersonal level, contextual, situational, and multicultural factors (i.e. race, sex, ethnicity, class, culture, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, acculturation, age, and other diversity indices) are related to men’s restrictive masculinity ideologies.

- The multicultural psychology of men studies the psychological costs of the macro-societal oppression that emanates from restrictive masculinity ideologies and GRC.

- Many different masculinity ideologies and identities exist based on racial, ethnic, age, nationality, religious, sexual orientation, and other situational indices of diversity that differentially predict, moderate, mediate, and cause GRC.

Examples of Gender Related Contexts

Gender role identity; fears of femininity; restrictive, sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies; patterns of gender role conflict; gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations;defense mechanisms; male vulnerability; psychological and interpersonal problems; internalized oppression; violence from GRC.

Assumptions:

- Gender role identity is negatively affected by the macro-societal contexts that are oppressive.

- Many different masculinity ideologies and identities exist based on racial, ethnic, age, nationality, religious, sexual orientation, and other situational indices of diversity that differentially predict, moderate, mediate, and cause GRC.

- Three gender-related contexts that negatively affect men’s gender role identity are: restrictive and sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies, the fear of femininity, and distorted gender role schemas.

- Contextual, situational, and multicultural factors (i.e. race, sex, ethnicity, class, culture, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, acculturation, age, and other diversity indices) are related to men’s restrictive masculinity ideologies, GRC, and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- The effects of a restrictive gender role identity produce patterns of gender role conflict, defensiveness, and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- Men experience vulnerability, societal discrimination, internalized oppression, psychological/emotional problems, and violence as a result of gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations

- GRC, defensiveness, and the gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations promote male vulnerability.

- The negative results of the macro-societal and the gender related contexts are internalized oppression, psychological and interpersonal problems, and violence.

- The micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives need to be studied to document both the positive and negative outcomes and consequences of male gender role socialization and GRC.

- Micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives can be understood with further conceptualization and work by applied behavioral scientists.

- Contextual, situational, and multicultural factors (i.e. race, sex, ethnicity, class, culture, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, acculturation, age, and other diversity indices) are related to men’s restrictive masculinity ideologies, GRC, and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

Examples of Research Contexts

GRC as predictor of men’s psychological problems; GRC as moderator of men psychological problems; GRC as mediators of men’s psychological problems; contextual and micro-contextual factors as predictors of GRC; GRC as a mediator of contextual and micro-contextual factors in predicting outcomes; descriptive-antecedent contexts; micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts; positive and negative situations related GRC; negative and positive behavior outcomes and consequences of gender related situations.

Assumptions:

- The micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives need to be studied by applied behavioral scientists to document both the positive and negative outcomes and consequences of male gender role socialization and GRC.

- Therapists and psychoeducational programmers can use gender role transitions, gender role schemas, GRC and the gender role journey with men in therapy and during preventive interventions

- Therapeutic and psychoeducational interventions can be developed to help men and boys heal from their GRC and their gender related problems.

Examples of Therapeutic and Psychoeducational Contexts

Gender role journey; readiness and motivation to change; evaluations of restrictive gender roles, sexism, and other oppressions; stages of change (pre-contemplative, contemplative, preparation, action, and maintenance; client’s presenting problem; masculine specific conflicts; gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations; deepening; gender role journey as portal; deconstruction of masculine and feminine roles; psychosocial assessment; gender role transitions; gender role schemas; distorted gender role schemas; macro-societal contexts; internalized oppression; GRC as the wound; GRC concealing the wound; GRC as a vehicle to discovering the wound; assessing masculinity ideology; assessing patterns of gender role conflict; assessing distorted gender role schemas; assessing gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations; transitions in gender role journey phases; restrictive emotionality; success, power competition; restrictive affectionate behavior between men; conflict between work and family relations; homophobia; critical issues during therapy; psychoeducational program for boys and men; GRC’s relationship to student development theory; Chickering and Reissner’s identity vectors.

Assumptions:

- Gender role journey phases can be used as a therapeutic framework to help men in therapy and during psychoeducational programming.

- Assessing a man’s phase of the gender role journey gives insights into his readiness and motivation for change.

- Men can be invited to take the gender role journey by asking them if they are open to evaluate how restrictive gender roles, sexism, other oppressions have affected them.

- The three phases of the gender role journey parallel the stages of change in therapy (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance) and relate to the man’s problems that maintain problems and constrain change (Prochaska and Norcross, 2010; Brooks, 2010).

- Phase 1 and 2 of the gender role journey are considered to be unhealthy or at least unsettled phases of the gender role journey and reinforce masculine specific conflicts and other problems in men’ lives.

- The gender role journey can be a way of helping men discover their masculine specific conflicts and emotional wounds experienced as gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- Facilitating a client’s gender role journey allows for deepening (Rabinowitz and Cochran, 2002) and prompt gender role transitions.

- The gender role journey serves as a possible portal to men’s problems. The gender role journey and GRC become a “….. a way to organize the thematic elements in the male client’s narrative as well as an entry or key to the deeper, emotional elements of images, words, thematic elements of the client’s inner psychological life (Rabinowitz & Cochran, 2002, p.26).

- Deconstructing masculine and feminine gender roles and stereotypes is the primary way to experience the gender role journey and help men resolve their GRC.

- Facilitating the gender role journey can occur by using interviewing, consciousness raising, psychoeducation, bibliotherapy, and use of masculinity measures.

- Psychosocial assessment of the clients’ development, their gender role transitions, and distorted gender role schemas can facilitate the gender role journey.

- Providing clients macro-societal and diversity contexts to their gender role journey can help them discern how sexism and other oppressions have contributed to their psychological problems including internalized oppression.

- GRC is a multifaceted dynamic for both clients and the therapists and needs to be monitored during therapy for positive therapy outcomes.

- Normalizing human vulnerability, wounds, and pain is critical to facilitating the gender role journey.

- Psychological defenses may need to be assessed and worked with during the gender role journey.

- Clients’ GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) can be a defenses that hide the portal and the masculine specific conflicts and inhibit movement through the gender role journey phases and the levels and processes of therapeutic change (Prochaska and Norcross, 2010; Brooks, 2010).

- Contextually, GRC may be a man’s wound, may conceal a man’s wounds, and may be a vehicle to discovering a man’s wounds.

- Assessing a man’s masculinity ideology, patterns of GRC, and distorted gender role schemas is critical during therapy.

- Assessing how the man devalues, restricts, and violate himself and others is key to finding the portal and resolving the GRC.

- Helping clients transition from one phase of the gender role journey to another by assessing and resolving the patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) can increase the deepening during the therapeutic process.

- The critical issue of transitioning men from one stage of change to another through the phases of the gender role journey occurs best with the resolution of the RE, SPC, homophobia, and control issues.

- Healing from gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations requires insights assertiveness, self-efficacy, risk taking, and personal and professional activism.

Early Conceptualization of GRC 1970s’ & 1980s’

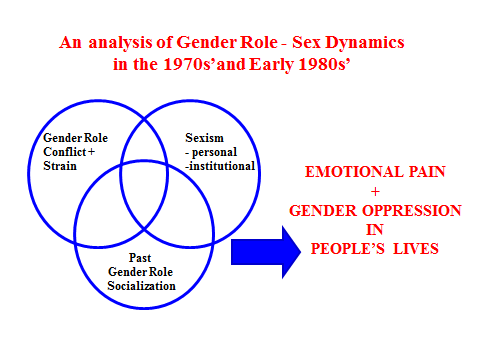

In the very early days of the research program, this simple diagram conveyed my overall sense of how gender role conflict interacted with past socialization and personal and institutional sexism causing gender oppression and psychological turmoil in both men’s and women’s lives. Since these topics were provocative a simple diagram was needed to begin dialogues and discussions.

The Counseling Psychologist Model 1981

Taken from: O'Neil, J. M. (1981). Male sex-role conflicts, sexism, and masculinity: Implications for men, women, and the counseling psychologist. The Counseling Psychologist, 9, 61-80.

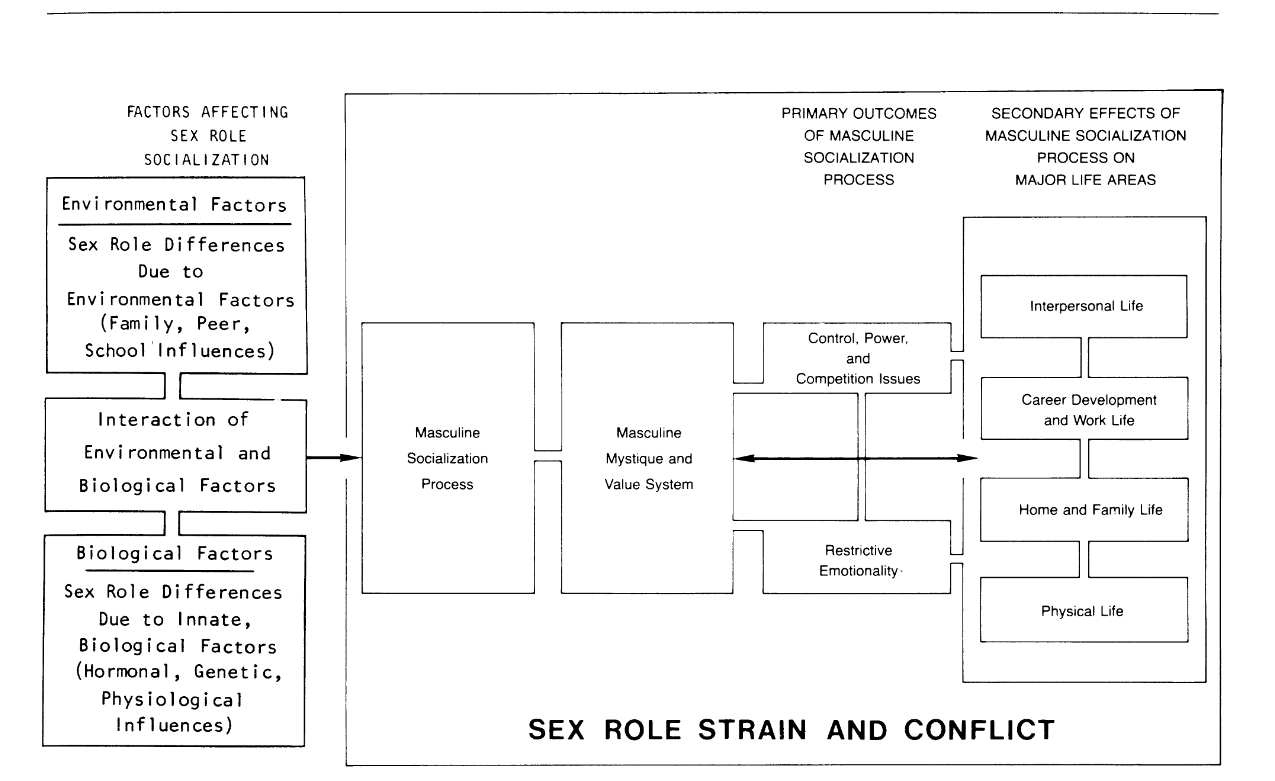

Figure 1 depicts the common themes found in the men’s literature and areas of sex-role strain and conflicts that emerge from the male socialization process. This model provides a simplification of complex biological, sociological, and psychological processes and represents a synthesis of the central themes in the literature concerning men’s sex role development and conflicts. The model was designed to initiate discussions and research on the specific sex role strains, conflicts, and problem areas that men may develop from the restrictive male sex role.

Figure 1 shows that men’s sex role socialization process is affected by both biological and environmental factors. Men’s sex role development is affected by their unique biological heritage and masculine values learned from their families, schools, peers, and other societal influences. These masculine values, taken collectively, represent a Masculine Mystique and Value System that reflects the current societal norms concerning what is appropriate and desired masculine behavior. This Masculine Mystique is defined as a complex set of values and beliefs that define optimal masculinity in a given society. Many of these values and beliefs are based on unproven sex differences and sex role stereotypes that are assumed to have value but may have negative outcomes for men, women, and children.

Figure 1 shows two primary outcomes of the Masculine Mystique that produce sex role strain and conflict for men. These outcomes include: a) restrictive emotionality and b) control, power, and competition issues. Restrictive emotionality is defined as having difficulty expressing one’s own feelings or denying other their rights to emotional expressiveness. The emotionally restricted person has difficulty in being vulnerable, self-disclosing, and in understanding and integrating the complexities of emotional life. Control implies to regulate, restrain, or to have others or situations under one’s command. Power is authority,, influence, or ascendancy over others. Competition is the act of striving against others to win or gain something. These primary outcomes have secondary effects on four major life areas for men: a) interpersonal life, b) career development and work life, home and family life, and d) physical life. Sex role strain and conflict occur when restrictive emotionality and control, power, and competition restrict people’s rights to act a certain way (e.g., masculine, feminine, androgynous) in a given situation. Sex role strain and conflict will vary considerably depending on early sex role socialization experiences and how narrowly the male sex role is defined. The degree and the kind of sex-role conflict will also vary depending on the man’s age, social class, cultural heritage, and geographic location.

The double arrow in Figure 1 shows that the primary outcomes of the masculine socialization process (restrictive emotionality) and control, power, and competition) interact and affect bot the Masculine Mystique and the four major life areas of men.

Early Model and Assumptions About Gender Role Conflict

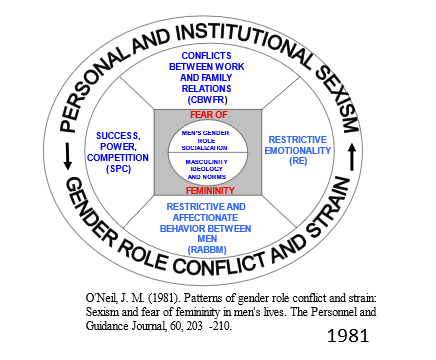

In this second model of GRC, men’s socialization and masculinity ideology and norms are show being shaped by the fear of femininity that promotes four patterns of gender role conflict (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR). The hypothesis was that personal and institutional sexism and GRC were related to men’s sexist gender role socialization, ideologies, and the fear of femininity. This model was explained with the 10 assumptions.

Assumptions About Gender Role Conflict and Sexism*

- Gender role socialization affects gender identity and personal beliefs about the nature of masculinity and femininity.

- Children socialized toward rigid stereotypes of masculine and feminine behaviors may learn restrictive attitudes and behaviors that limit their growth and ability to cope with the complexities of adult life.

- Rigidly socialized masculine or feminine stereotypes about men and women can produce gender role conflict and sexism.

- Gender role conflict and sexism can produce considerable psychological stress for men and women.

- Gender role conflict and sexism have caused men and women to devalue one another in order to solidify their own gender identities.

- The devaluation of women by men and the devaluation of men by women is a central concept in understanding how personal and institutional sexism operate in society.

- Neither sex is exclusively responsible for learned sexism emanating from gender role socialization or conflict. Men and women both contribute to the maintenance of restrictive gender roles that produce gender role conflict, and both sexes need to take personal responsibility for how gender role conflict and sexism restrict their own or other’s human potential.

- Most people will experience varying degrees of stress due to their gender role socialization, gender role stereotypes, and sexism.

- Gender role conflict can be better understood if we continue to assess how gender role socialization, gender role conflict, and sexism mutually interact and affect our relationships with each other.

- Counselors and other human service providers need to be prepared to help men and women who are experiencing the effects of sexism and gender role conflict.

Diagnostic Schema Explaining Men’s Gender Role Conflict

| Assessment Model 1: Diagnostic Schema for Assessing Men's GRC | |||

| Personal Experience and Outcomes of Gender Role Conflict: SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR | GRC Within Self | GRC Caused by Others | GRC Inflicted on Others |

| D. Gender Role Conflict Devaluations | D1 Self Devaluation How does the man devalue himself because of masculinity ideology & GRC? |

D2 Devaluation by Others How is the man devalued by others because of masculinity ideology & GRC? |

D3 Devaluation of Others How does the man devalue others because of their masculinity ideology & GRC? |

| R. Gender Role Conflict Restrictions | R1 Self Restriction How does the man restrict himself because of masculinity ideology & GRC? |

R2 Restriction by Others How is the man restricted by others because of masculinity ideology & GRC? |

R3 Restriction of Others How does the man restrict others because of their masculinity ideology & GRC? |

| V. Gender Role Conflict Violations | V1 Self Violation How does the man violate himself because of masculinity ideology & GRC? |

V2 Violation by Others How is the man violated by others because of masculinity ideology & GRC? |

V3 Violation of Others How does the man violate others because of their masculinity ideology & GRC? |

| GRC= Gender role conflict, SPC = success/power competition, RE = restrictive emotionality, RABBM = restrictive/affectionate behavior between men, CBWFR = Conflict between work and family relations

from O'Neil 1990, 2015 |

|||

Schema Explaining Men’s Personal Experiences of Gender Role Conflict (GRC)

Table 1 depicts a schema that explains men’s personal and interpersonal experiences of GRC. On the left of the Table 1 are the personal experiences and outcomes of GRC including gender role devaluations, gender role restrictions, and gender role violations. Across the top of Table 1 are shown the three situational contexts of these experiences: Within Self, Caused By Others, and Expressed Towards Others. These three situational contexts are defined as how and from whom GRC is experienced by an individual man. These situational contexts demonstrate that devaluations, restrictions, and violations can exist within a man (the intrapersonal context) or emanate from others, or be expressed toward others (the interpersonal contexts).

In the center of Table 1 are 9 assessment cells that explain men’s personal and interpersonal experiences of GRC. For example, self-devaluation from GRC would be Cell D1, whereas GRC devaluation by others or devaluation expressed toward others would be Cell D 2 and D3, respectively. Likewise, gender role restrictions and violations within self, caused by others, or expressed toward others are represented by Cells R1, R2, and R3 and Cells V1, V2, and V3, respectively.

A careful study of the nine cells provides an operationally defined method of understanding men’s experience of GRC and connecting it to their problem or symptom. In each cell there is a diagnostic question relevant to assessing a man’s GRC and masculinity ideology. For GRC Within Self (Cells D1, R1, V1), the question is “How does the man devalue, restrict, or violate himself because of masculinity ideology and GRC? Answering this question in the context of men’s symptoms can help explain how masculinity ideology and GRC contribute to the man’s problems. For GRC Caused by Others (Cells D2, R2, and V2), the question is: How is the man devalued, restricted, and violated by others because of his masculinity ideology and GRC. Answers to this question can help the man see how he is treated by others who demand conformity or nonconformity to expected gender roles. For GRC expressed Towards Others (Cells D3, R3, and V3), the question is: How does the man devalue, restrict, or violate others because of his masculinity ideology and GRC? This question focuses on a man’s masculinity ideology and GRC and how he treats others when endorsing or rejecting traditional gender roles. The 9 cells provide the most personal, contextually sensitive, and situationally focused ways to assess men’s personal experiences of GRC in the context of their presenting problem.

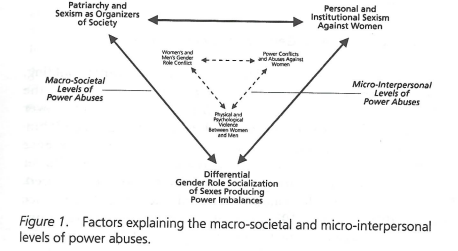

Abuses of power against women: Sexism, gender role conflict, and psychological violence

Figure 1 depicts the complexity of factors affecting the power and gender role dynamics in men’s and women’s livers. The relationship among these factors is discussed here. Two triangular levels of analysis depict how power and gender role interact at both the macro-societal and micro-interpersonal level. The macro-societal level is represented by the outer triangle. This level includes three factors: 1) patriarchal and sexist structures as organizers of society, 2) personal and institutional sexism against women, 3) the differential gender role socialization of the sexes that produces power differences. The bi-directional arrows for these three factors indicate that societal patriarchy, sexism, and gender role socialization are directly related to one another in complex ways. These three factors represent the political-social etiology of abusers of power against women.

The inner triangle depicts the micro-interpersonal expression of the macro-societal factors. These factors include: 1) women’s and men’s gender role conflict, 2) power conflicts and abuses of power against women, and 3) physical and psychological violence between men and women. The bi-directional arrows indicate that power conflicts and abuses, gender role conflict, and psychological violence are related to one another in complex ways. Whether power abuses cause gender role conflict, or vice versa, is affected by the individual involved and the situational context. Likewise, whether power conflicts and gender role conflict cause psychological violence, or vice versa, also depends on the situation and the individuals involved. It is difficult to state categorically which of these factors causes the other because of the variability of situations and people’s different gender role socialization experiences.

The question of how power abuses relate to men’s and women’s socialization and how they cause gender role conflict and psychological violence has gone unexplored. Power abuse, psychological violence, and gender role conflict are all complexly interrelated in ways that defy simple explanations. When men and women face this complexity, there may be difficulty in communicating and problem solving. Many times the complexity is reduced to anger, misunderstanding, and hopeless despair. What is rarely discussed, but usually clear, is that women’s and men’s lives are negatively affected by the relationship of power and gender roles.

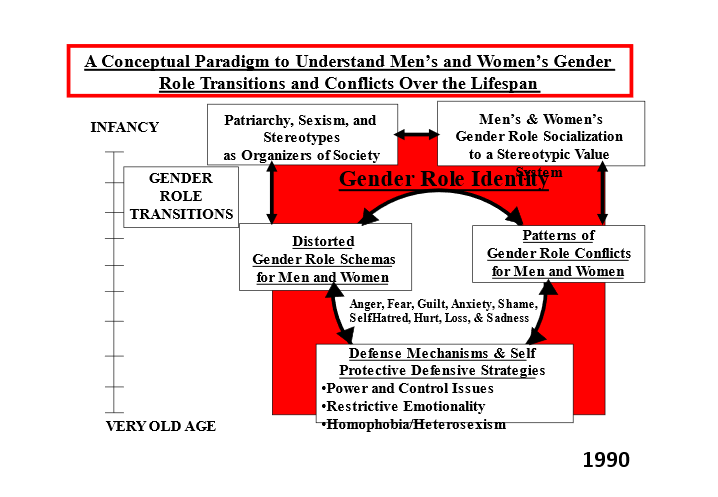

A Conceptual Paradigm to Understand Men’s and Women’s Gender Role Transitions and Conflict Over the Lifespan

Five theoretical premises were the basis for this model--

Men and Women Can:

- Be socialized in sexist ways by our patriarchal society into restrictive gender role values and beliefs.

- Develop gender role identities based on restrictive and sexist gender role stereotypes during gender role socialization. Learn distorted gender role schemas of masculinity and femininity during gender role transitions and gender role socialization

- Experience these distorted gender role schemas as fears and negative emotions including: anger, fear, anxiety, shame, guilt, loss, sadness, self-hatred, and hurt.

- Develop patterns of gender role conflict that inhibit human growth and development across the lifespan and that can become potential mental health problems.

- Develop self-protective defensive strategies and use defense mechanisms to protect their gender role identity when coping with gender role conflict and negative emotions.

Conceptual Model Explaining Men’s Violence Against Women From a Gender Role Conflict and Gender Role Socialization Perspective

Taken from J.M. O’Neil & R.A. Nadeau. Mens gender role conflict defense mechanisms and self-protective defensive strategies: Explaining men’s violence against women from a gender role socialization perspective. In M. Harway & J.M. O’Neil (1999) (Eds.) What causes men’s violence against women? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

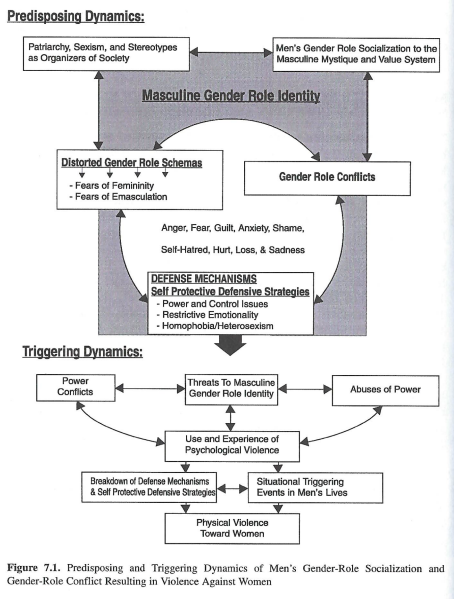

Figure 7.1 presents a conceptual model that explains how the larger patriarchal society, men’s gender role socialization, gender role conflict, and self-protective defense strategies, and traditional defense mechanism contribute to men’s violence.

Figure 7.1 depicts both the predisposing and triggering dynamics of men’s violence against women. The predisposing dynamics are defined as the gender-role-related factors and processes that render men vulnerable to using violence against women. The triggering dynamics are the actual situational cues and interpersonal processes that prompt men to psychologically or physically assault women.

At the top of Figure 7.1, on the left, the predisposing dynamics show the larger patriarchal society as the spawning ground for men’s sexism and violence toward women. The larger patriarchal society, sexism, and gender related stereotypes are shown as organizers of our society. Patriarchy instills sexist values and stereotypes that influence how men related to women, to other men, and to themselves.

In the top-right corner of Figure 7.1 men’s gender-role socialization and, specifically, the Masculine Mystique and Value System are shown. The Masculine Mystique is a complex set of sexist values and beliefs that define optimal masculinity in society and in men’s lives. Masculine gender-role identity is formed by the overall patriarchy and men’s sexist socialization to the values of the Masculine Mystique. This identity is continually shaped by four interacting and socializing dynamics shown in the middle of Figure 7.1.

First distorted gender role schemas are learned during a boy’s gender role socialization. These distorted gender-role schemas produce a fear of femininity and fears about being emasculated.

Second, gender role conflicts that occur in boy’s and men’s lives may potentially be emasculating for them.

Third, as shown in the middle of the circle of Figure 7.1, men experience as spectrum of negative emotions, such as anger, fear, guilt, anxiety, shame, self-hatred, hurt, loss, and sadness, during their gender role socialization. They respond to these emotions by experiencing fears of femininity and fears of being emasculated that threaten their masculine gender role identity.

Fourth, men develop traditional defense mechanism and three self-protective defense strategies to cope with their negative emotions. The self defensive strategies operate to mediate men’s negative feelings and increase their ability to cope with gender role conflict. These self-protective strategies include a) power and control, b) restrictive emotionality, and c) homophobias/heterosexism. In short, these self protective defense strategies keep men temporarily safe, but do not effectively resolve the gender role conflict and negative emotions about their masculine gender role identity.

The bidirectional and circular arrows at the top and in the middle of Figure 7.1 depict the complex relationships between the concepts and processes that predisposing men to use violence. The multiple arrows show how the macrosocietal aspects of sexism and patriarchy interact in complex ways with the man’s gender role identity and his psychological sense of self.

The large, bold-faced arrow at the bottom of the defense mechanism and strategies depicts how the entire set of predisposing dynamics affects the triggering dynamics at the bottom of Figure 7.1

Men’s psychological and physical violence toward women is triggered when their defenses and self-protective defense strategies break down. As shown in the bottom half of Figure 7.1, power conflict, abuses of power, and psychological violence can increasingly pose threats to a man’s gender role identity. When couples have power conflicts, abuses of power may occur. Couples may use and experience psychological violence as conflicts go unresolved, thereby increasing the interpersonal tension and potential for violence. Situational triggering events in men’s lives or the family situation (unemployment, health problems, extramarital affairs, parenting dilemmas, money problems) may serve as the stimulus for greater and greater threats to the man’s gender role identity. When men’s self-protective defense strategies and defense mechanism no longer work (i.e., they partially or completely break down), the potential for psychological and physical violence is hypothesized to be high.

The bi-directional arrow at the bottom of Figure 7.1 shows the complex relationship between the factors that trigger violence. Power conflicts, abuse of power, psychological violence, and threats to a man’s gender role identity are the interrelated factors that contribute to triggering men’s violence. How these factors operate in a man’s life is quite idiosyncratic and interacts with the overall dynamics of the couple’s relationship.

In summary, the conceptual model explains how men might learn to be violent toward their partners from a gender role socialization perspective. The model relates directly to the hypothesis that men’s sexist gender role socialization, misogynistic attitudes toward women, patterns of gender role conflict, and unresolved and unexpressed emotions contribute to men’s violence against women.

Ten theoretical assumptions about men and their abuse of power and violence toward women include:

Many Men in General and Specifically Violent Men

- Are socialized in sexist ways by our patriarchal society into restrictive values of the Masculine Mystique and Value System.

- Learn distorted gender role schemas of masculinity and femininity during their gender role socialization.

- Learn distorted gender role schemas of masculinity and femininity during their gender role socialization.

- Learn distorted gender role schemas that produce fears of femininity, fears of emasculation, and gender role conflict.

- Experience negative emotions from their gender role conflict including: anger, fear, anxiety, shame, guilt, loss, sadness, self-hatred, and hurt.

- Develop self protective defensive strategies and use defense mechanisms to protect their masculine gender role identity when coping with gender role conflict and negative emotions.

- Are predisposed to be dysfunctional, abusive, and sometimes violent with women because of their gender role conflict and learned defensiveness.

- Abuse power and are defensive during power conflicts with women, particularly when loss of power or control are at stake and when their masculine gender role identity is threatened.

- Use psychological violence and threats against women when the self-protective defensive strategies begin to break down and traditional defenses no longer work.

- Use violence against women when triggering events occur in the couple’s life and when defense strategies no longer work and defense mechanisms break down.

Gender Role Conflict and Fathering Contexts

Fathering Contextual Model

The covert contexts of fathering provide a rationale for clinicians to assess a father’s problems and psychological functioning. The model shown in Figure 1 depicts fathering contexts related to GRC and ineffective parenting. Arrows A1 and B1 imply that restrictive masculinity ideology, unfinished problems with one’s father, and the father wound are related to higher GRC. Furthermore, the model implies that higher GRC relates to inconsistent, inept, ineffective, dysfunctional, and dissatisfying fathering. Research and theory exist to support the relationship of masculinity ideology with GRC, as shown by arrow A1 (O’Neil, 2008; Pleck, 1995; Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1993). No empirical research has documented that clients’ unfinished business with their fathers or the father wound relate to GRC as is implied with arrow B1. There is some research indicating that higher GRC may relate to ineffective fathering for men in general (Alexander, 1999; DeFranc & Mahalik, 2002, McMahon, Winkel, & Luthar, 2002; O’Neil, 2008) as depicted in Figure 1, but no research has been completed with fathers who are clients. The concepts in Figure 1 are operationally defined and discussed in subsequent sections.

Diagnostic Schema to Assess Fathers During Therapy

From: O’Neil, J.M. & Lujan, M. L. (2009) An assessment paradigm for fathers in therapy using gender role conflict theory. In C. Z. Oren & D. C. Oren (Eds.) Counseling fathers. Taylor & Francis Group.

Therapist’s Knowledge of the Psychology of Men and Fathering, Bias Against Men, and Self Analysis of Personal Fathering Conflicts

This self-assessment area has three dimensions. Therapists need to assess their knowledge about fathering and the psychology of men. Therapists can assess the knowledge they have on fathering and the psychological consequences of restrictive gender roles. No standard curriculum currently exists on what therapists should know when doing therapy with men in the context of GRC. Until such a curriculum exists, therapists should consult with the current authorities on therapy with men (Brooks & Good, 2001; Englar-Carlson & Stevens, 2006; Pollack & Levant, 1998; Rabinowitz & Cochran, 2002). Furthermore, therapists should also consult the literature on fathering and its relevance to helping men (Kiselica, 1995; Lamb, 2004; Osherson, 1987; Shapiro, 2001).

Another critical domain for therapists to assess is biases towards fathers and men. Therapists’ biases against men have been documented (Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1990), but few studies have assessed prejudice against fathers. Two studies have shown that therapists’ GRC significantly relates to having less liking for nontraditional and homosexual men (Hayes, 1985; Wisch & Mahalik, 1999). Current stereotyping and having biases against men are probably as frequent as they were with women in the 1970s (Brodsky & Holroyd, 1975). Therefore, therapists need to evaluate continuously the degree that their stereotypic biases may affect their assessment of fathers.

The third issue is therapists’ awareness of unfinished business or father wounds they might have with their own fathers. This is a critical counter transference issue when using fathering as a diagnostic category. Therapists can assess whether they have unresolved conflicts with their own fathers that may interfere with the therapy processes. Without this awareness, therapists may not recognize a client’s problems with fathering and avoid discussing it. Expressed more precisely, counter transference may impede the therapeutic process.

Assessing Father’s Masculinity Ideology and Norms

Assessing masculinity ideology and norms with fathers includes probing values and standards that define, restrict, and negatively affect a man’s life. There are numerous questions that can be asked about masculinity ideology during therapy. The critical question is what internalized masculine values does the client have that restrict his approaches to fathering? More specifically, how much do rigid, sexist, or stereotypic values impede positive fathering? Were these masculine values learned from the client’s own father? Therapeutic questions about a client’s masculinity ideology can be an important part of therapy with men. Many fathers may not know any alternative male values to replace restrictive and sexist ones. The therapist can help the client discern new values that are not sexist or restrictive. This therapeutic process involves discussing the healthy aspects of men’s gender roles and patterns of positive masculinity with fathers (O’Neil & Luján, in press; Luján & O’Neil, 2008). This means identifying men’s strengths, such as responsibility, courage, altruism, resiliency, service, protection of others, social justice, perseverance, generativity, and non violent problem solving. This kind of activity moves away from what is wrong with men and fathers to identifying the qualities that empower men to improve their fathering, their families, and their lives.

Assessing Father’s Defenses

Discussion of a man’s fathering and his past experiences as a son are issues that may activate psychological defenses. To our knowledge, no studies have correlated men’s defensiveness and problems with fathering. Defensiveness is important to assess because many theorists have conceptualized men’s socialization experiences as a defensive process (Boehm, 1930; Jung, 1953; O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). Defensiveness may serve various functions for fathers that therapists can actively assess. For example, defensiveness can mediate difficult and powerful emotions, help men cope with fears about appearing feminine or being emasculated, and help men protect against perceived losses of power and control. These defensive functions could be important vantage points to understand fathers in therapy. Additionally, therapists can point out that defensiveness can produce restrictions in thought and behavior, emotional and cognitive distortions, over-reactions, cognitive blind spots, and increased potential for restriction and devaluation of others (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). The client can consider how these defensive postures affect his parenting or other parts of his life.

Therapists can directly explore a client’s defensiveness about his father or fathering competence. One quick way to assess whether there is defensiveness related to a client’s fathering is to ask some pointed questions. For example, the client could be asked - How does your relationship with your father affect: a) your current problems as a man? b) your effectiveness as a father with your own children? Verbal and nonverbal responses to these questions could determine how to proceed with the therapeutic process. Wherever there are strong defenses, there are also usually deep emotions. The assessment of defensiveness about fathering can also be a strategy to uncover repressed or difficult emotions about one’s own father or fathering.

Assessing Father’s Distorted Cognitive Schemas About Fathering

Distorted cognitive schemas about fathering are inaccurate, narrow, and sexist views of gender roles as they impact fathering. Distorted cognitive schemas develop when men experience pressure, fear, or anxiety about meeting or deviating from stereotypic notions of masculinity. Many men have internalized a definition of fathering that is based on rigid and patriarchal values. The traditional definition of fathering exclusively focuses on provider roles, discipline, protection, and enforcement of a moral code. Traditional definitions of fathering have excluded important emotional, psychological, and educational processes. Therefore, traditional fathering may not include active involvement with such important male issues as emotional development, introspection, spiritual and sexual education, self confidence, fears of failure, problem solving, and decision making. Some fathers may define these issues as feminine, women’s work, and not part of traditional masculinity ideology.

What can therapists do with distorted cognitive schemas about fathering? Mahalik (1999, 2001) has identified four steps in helping men with their distorted cognitions including (a) assessing the specific areas of men’s cognitive distortion; (b) educating men about how cognitions, feelings, and behaviors are interrelated; (c) exploring the illogical nature and accuracy of the cognitive distortions; and (d) modifying the biased distortions with more rationality. These steps provide a useful framework for working with distorted cognitive schemas, GRC, and fathering issues. Exploring and resolving fathers’ distortions about the meaning of masculinity and fathering can enhance the therapeutic alliance and set the stage for emotional release and effective problem solving

Assessing Father’s Acculturation, Diversity, and Oppression

There is diversity with fathering values and attitudes based on race, class, age, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and acculturation experience. Therapists and clients can explore how ethnic, racial, and acculturation variables affect fathering attitudes and values. Different races, classes, and ethnicities approach fathering in unique ways that need to be understood. For those fathers who have acculturated to American society, there may be contradictions in fathering values between this society and their society of origin. The therapist may need to help the man understand his parenting in the context of his racial, ethnic, and cultural identity (Wester, 2008). Therapists can help fathers reconcile conflicted values about fathering in terms of their cultural and bicultural identities. Therapists also need to consider how diversity variables can promote positive parenting and how they can produce barriers. Most importantly, these diversity issues need to be understood in the context of the overall societal demands on men that can be oppressive and sexist.

Personal oppression from sexism, racism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, or any other discrimination needs to be assessed in the context of any man’s fathering role. An oppressed man is usually angry, humiliated, emasculated, and vulnerable. For example, a father who cannot provide for his family (a basic masculine mandate in our society) because of racism is likely to feel angry, vulnerable, worthless, shamed, embarrassed, desperate, and inadequate as a man. When a man experiences these emotions, effective fathering may become irrelevant or less important. Survival and how to avoid further discrimination and humiliation may become the main priority. Some men will compensate for the oppression by becoming hypermasculine or aggressive. Oppression, discrimination, and poverty are not conducive to effective fathering and are serious barriers to many men’s desires to be positive fathers. Therapists need to have multicultural, acculturative, and diversity perspectives on fathering when working with a wide array of men.

Assessing the Father Wound

Assessment of the father wound during the therapy process is complex. Many times assessing the family of origin can help the therapist explore whether the client has internalized a father wound. Sometimes, simple exercises or homework assignments can uncover the wounds. For example, having a client draw a picture of his overall relationship with his father in the past or present can bring wounds into clear focus. Another activity could be writing a brief essay on the quality of the relationship with his father as a young boy. Having the client bring in a picture of his father can help focus the discussion of the father-son relationship. Many times, the path to healing is through increased compassion for the father’s wound as he experienced it.

Assessing Father’s Patterns of Gender Role Conflict

Therapists can assess the four empirically derived patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) in the context of men’s fathering roles and functions (See Figure 2). The assessment of men’s patterns of GRC as part of the therapy process has support from the research. All four GRC patterns have significantly correlated with depression, anxiety, stress, low self esteem, shame, intimacy problems, marital dissatisfaction, homophobia, attachment problems, and abuses of women (O’Neil, 2008). The GRC patterns and these problems can impede effective fathering. For example, fathers need to be able to process their own emotions and the feelings of their children since family life can be emotionally charged. Constructive use of power and control is critical in successful parenting as sons and daughters test limits and challenge authority. Restriction of affectionate behavior can produce distance between fathers and their children. The CBWFR is a critical problem to be resolved because stress and fatigue do not contribute to effective fathering.

Direct questioning of clients about the degree to which they experience the patterns of gender role conflict is one way to assess fathers. Additionally, the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS) and the Gender Role Conflict Checklist (O’Neil, 1988) can be used as diagnostic tools both in therapy (O’Neil, 2006; Robertson, 2006) and workshops for men (O’Neil, 1996, 2001; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988). The direct assessment of GRC can help clients develop a gender role vocabulary that can help them understand their psychological problems. Identifying GRC patterns can also stimulate discussion and emotional disclosure about the personal experience of fathering. One of the primary roles for the therapist is to listen to the client’s story about being a man, interpret the story from a gender role perspective, and provide support for making healthy changes.

Assessing Self Efficacy in Fathering and Need for Information About Fathering

In our literature search we found information about parenting self efficacy but no specific theory or measures on fathering self efficacy. Fathering self efficacy is defined as the father’s belief in his ability to effectively fulfill parental roles, functions, and responsibilities. As with attitudes about problem solving (Heppner, Witty Dixon, 2004), we hypothesize that a father’s belief in his ability to father effectively is one of the most critical variables in actually developing positive fathering. From our perspective, fathering self efficacy is more likely to occur if fathers have useful information on fathering roles, functions, and processes. Many fathers will have insufficient information about how to father, and this lack of information can produce insecurities about parenting or unrealistic norms about positive fathering. Therapists can be a source of information on the positive effects that fathers can have on their children. Books and articles can be given to fathers to help them develop a personal framework for parenting and how to create enjoyable fathering.

Many fathers can obtain needed information and fathering skills in psychoeducational group programs. These psychoeducational interventions can be developed by mental health professionals using the content in Figures 1-3. Changing strongly socialized attitudes about fatherhood may require potent interventions over extended periods of time. Furthermore, how to attract men to these fathering programs may require creative advertising. Research indicates that titles and formats can activate negative attitudes about help seeking (Blazina & Marks, 2001; Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1992; Rochlen, McKelley, & Pituch, 2006). Fathering programs should be described in positive terms that communicate men’s strengths and vitality.

Descriptive Contextual Model of Men’s Gender Role Socialization and GRC

Figure 2 : Descriptive Contextual Model of Men’s Gender Role Socialization and GRC

Figure 2 depicts a new descriptive model that expands our contextual understanding of gender roles and GRC. The new contextual model has three separate but related parts: a) psycho-social developmental contexts, b) macro-societal contexts, and c) gender related contexts. The purpose of this model is to convey descriptive (generalized) contexts to understand men and their GRC. First, on the left and at the bottom are the life stages, psychosocial developmental contexts, and the gender role transformation and growth through healthy positive masculinity. Second, the black and bold triangle in the middle of the figure, with the three boxes, is the macro-societal context. This context includes: a) patriarchy, hegemonic masculinity, sexism, stereotypes, as organizers of society, b) personal and institutional oppression from discrimination that creates social injustice, and c) stereotypes and differential socialization of boys and girls to sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies. Finally the gender related contexts are all concepts inside the bold triangle shown as two trapezoids. The gender related context focuses on gender role identity and the patterns of GRC. The gender role identity context is shaped by situational, biological, unconscious, familial, multicultural, racial, and ethnic contingencies, b) restrictive and sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies, c) fear of femininity, d) distorted gender role schemas. In the second trapezoid, the patterns of gender role conflict, as the negative outcomes of sexism and other oppressions, are discussed in the context of defensiveness, gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations, and male vulnerability. Both the macro-societal and gender related contexts point directly to the rectangle at the bottom showing men’s psychological and interpersonal problems, internalized oppression, and violence.

All developmental stages and psychosocial processes on the left of Figure 2 are affected by the contexts within the bold triangle resulting in possible psychological and interpersonal problems. In other words, gender related conflicts that cause psychological problems can occur anytime throughout the life cycle from early childhood to very old age. The directionality of the pointed bold triangle does not imply that they are only experienced at the very old age end of the life cycle. GRC can occur at any point in the life cycle and the same is true for the gender role transformation and growth processes shown at the bottom of the page. Each of these descriptive contexts include expanded conceptual knowledge about men and are defined below.

Table 3 enumerates 14 theoretical assumptions that represent the ideas in Figure 2

Table 3 New Theoretical Assumptions About Men’s GRC

__________________________________________________________________

- Descriptive–antecedent contexts can be identified in men’s lives that help explain men’s GRC and possibilities for growth to healthy positive masculinity.

- Gender role development, transitions, and transformations are experienced while mastering the developmental tasks and psychosocial crises over the lifespan.

- Journeying with gender roles over the lifespan and managing gender role transitions are part of seeking positive and healthy masculinity.

- Macro-societal contexts negatively restricts male gender role socialization and include patriarchy, sexism, restrictive stereotypes, oppression and social injustices, and the differential socialization of boys and girls to sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies.

- Gender role identity is negatively and positively affected by the macro-societal contexts.

- Situational, biological, unconscious, familial, multicultural, racial, and ethnic contingencies shape gender role identity in both positive and negative ways.

- Three gender-related contexts that negatively affect men’s gender role identity are: restrictive and sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies, the fear of femininity, and distorted gender role schemas.

- The effects of a restrictive gender role identity produce patterns of gender role conflict, defensiveness, and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- GRC, defensiveness, and the gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations promote male vulnerability.

- The negative results of the macro-societal and the gender related contexts are internalized oppression, psychological and interpersonal problems, and violence.

- The micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives need to be studied to document both the positive and negative outcomes and consequences of male gender role socialization and GRC.

- Micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives can be understood with further conceptualization and work by applied behavioral scientists.

- Therapeutic and psychoeducational interventions can be developed to help men and boys heal from their GRC and their gender related problems.

- A call to action is needed to advance the psychology of men in theoretical, research, and psychological service domains.

Summary of Descriptive Contextual Model

Figure 2 provides many concepts to understand men’s problems in a broad, descriptive contextual sense and represents a substantial expansion of the earlier GRC theory and makes new conceptual connections not made before. Figure 2 provides an expanded number of descriptive contexts to think about men’s lives in a developmental, macro-societal, and gender related ways. The contexts have potential for stimulating future GRC research but other concepts in the psychology of men could be substituted in the figure, and therefore the model is only one way to explain men’s problems from restrictive gender roles. Researchers and theoreticians are encouraged to add (or substitute) their own concepts to the theoretical formulations in Figure 2 to broaden the contextual understanding of men’s GRC and healthy, positive masculinity.