- Introduction to Gender Role Conflict (GRC) Program

- Overall Information about GRC- Books, Summaries, & History

- Gender Role Conflict Theory, Models, and Contexts

- Recently Published GRC Studies & Dissertations

- Published Journal Studies on GRC

- Dissertations Completed on GRC

- Symposia & Research Studies Presented at APA 1980-2015

- International Published Studies & Dissertations on GRC

- Diversity, Intersectionality, & Multicultural Published Studies

- Psychometrics of the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS)

- Factor Structure

- Confirmatory Factor Analyses

- Internal Consistency Reliability Data

- Internal Consistency & Reliability for 20 Diverse Samples

- Convergent & Divergent Validity of the GRCS Samples

- Normative Data on Diverse Men

- Classification of Dependent Variables & Constructs

- Authors, Samples & Measures with 200 GRC Guides

- Correlational, Moderators, and Mediator Variables Related to GRC

- GRC Research Hypotheses, Questions, and Contexts To be Explored

- Situational GRC Research Models

- 7 Research Questions/ Hypotheses on GRC & Empirical Evidence

- Important Cluster Categories of GRC Research References

- Research Models Assessing GRC and Hypotheses To Be Tested

- GRC Empirical Research Summary Publications

- Published Critiques of the GRCS & GRC Theory

- Clinically Focused Models, Journal Studies, Dissertations

- Psychoeducation Interventions with GRC

- Gender Role Journey Theory, Therapy, & Research

- Receiving Different Forms of the GRCS

- Receiving International Translations of the GRC

- Teaching the Psychology of Men Resource Webpage

- Video Lectures On The Gender Role Journey Curriculum & Additional Information

The evolution and history of the GRC research program has been summarized in three publications that may interest researchers and clinicians. The links to these publications are found below.

My Gender Role Journey with the Gender Role Conflict Research Program

My Gender Role Journey with the Gender Role Conflict Research Program (1975-2014)

Published In:

O’Neil, J.M. (2015) My personal gender role journey with the gender role conflict research program. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 29-38. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

“Men adopt self-destructive and alienating male roles, not because men are evil or stupid, but because a sexist society confers real power on those who conform to male supremacist values.” (Harry Brod, 2013)

My study of men began with my first professional position as a professor and psychologist in the University Counseling Center at the University of Kansas. Fresh out of graduate school in 1975 at age 27, I had clinical and teaching responsibilities and a tenure track position that meant developing a research program and publishing. My interest in restrictive gender roles and oppression as a mental health problem began in my undergraduate and graduate school education. As an undergraduate at Le Moyne College, I learned from the Jesuits that injustices in society require an active response from spiritually evolved persons. As a graduate student in the University of Maryland’s Counseling and Student Personnel Program, my mentors were activists who researched racism and restricted gender roles and how they presented critical mental health issues.

During this time, women feminists asked significant questions about men’s problems, abuse, and violence. I listened and wanted to be part of the dialogue on these important issues. Some radical feminists who were separatists dismissed me without any dialogue. The separatist feminists were making statements like: “All men are oppressors,”” “All men rape,” and “All men should be blamed for the pervasive sexism against women in American society.” During those days, the verbal attacks upon men (i.e., male bashing) were less subtle than today. Naturally those statements got everyone’s attention and led to much polarization. Their anger, rage, and very relevant questions certainly got my attention and increased my commitment to Feminism and both women and men’s issues.

The more moderate feminists, thought it might be important to study men. They also asked important questions but I had also few answers to the issues they raised. I wanted to understand how sexism could produce such intense anger towards me, other men and the patriarchal system. Those were lonely days for me, not only for these political reasons, but because there was little support for my interest in men. Furthermore, I was starting my own gender role journey (O’Neil, Egan, Owen, & Murry, 1993; O’Neil & Egan, 1992a) and discovering my own pain from my sexist socialization.

There were colleagues scattered across campus who were interested in gender roles but it was graduate students who were a source of support and stimulation. The students would listen and helped create a scholarly environment for the study of men. Sitting there in my counseling center office in 1978, I remember pondering the many questions feminists were asking about men’s violence, sex discrimination, harassment in the workplace, and men’s abusive power and control at work and in family relationships. I knew there must be a reason why men were sexist and that it was more complex than reducing all men to innate oppressors who were misogynists. I reasoned that there must be something in the capitalist or family system that contributes to men’s sexism against women. Part of my problem was that I had no conception of how patriarchy worked and how sexism was a political reality in my own life. What really bothered me was that I could not answer the reasonable questions that Feminists were asking about men’s problems.

From that time on, men's gender role conflict (GRC) became a major part of my professional life and my primary research program. I wanted to develop a theory and research program that explained how sexism and gender roles interacted to produce oppression for both sexes. During those early days, I felt that both sexes were victims of sexism. Women as victims of sexism could be easily documented, but men as victims was harder to document, and harder still to conceptualize. The GRC construct was one way to conceptualize about sexism against men. Those heated discussions with Feminists in the 1970's were the primary stimuli for creating research on men's GRC.

The Literature Review and My Gender Role Journey

I thought some explanation for men’s problems could be found in the psychological journals and so I obtained a grant from the University of Kansas to research the literature on men and masculinity. In 1977 I began my review hoping to create some conceptualizations that might respond to the questions that Feminists were asking. I wanted to explain why men were violent, interpersonally rigid, sexist, homophobic, unemotional, and unhappy with themselves and others.

When I started the research on men, some of my male colleagues had some questions and concerns. They wondered about my topic and me. On some level they recognized that the topic was about them and it was unsettling. Some colleagues thought I was gay because I was studying men. One day I stared down unconscious homophobia when a colleague said in sarcastic, high-pitched, girly voice: “We heard you’re REALLY into men these days”. The sexual innuendo certainly got my attention. Finding my research on men suspect was one thing, but challenging my heterosexual identity – well that brought the dynamics to a new level of conflict and threat. Also there were a couple of gay men who were interested in getting to know me better and so I had to manage my responses to them. Having people think that I was gay was a new experience and prompted an examination of my homophobia and heterosexism. I remember thinking that studying men is taking me places that I never knew existed in my life.

Some women Feminists thought my motivation to study men was to justify men’s problems and violence. What I was trying to do was just the opposite: explain how men’s restrictive gender roles contribute to violent, abusive and controlling behaviors in relationships. These were difficult days in my gender role journey (O’Neil & Egan, 1992 a,; O’Neil, et al., 1993). My own hyped emotions and the confrontational interpersonal dynamics convinced me that studying men’s lives was going to be a challenging but provocative opportunity for my personal and professional growth. Sometimes I was anxious but moreover I was excited, enthused, and energized.

My Gender Role Journey

My four-month-long literature review was disappointing because I found very little information on men in books and the professional journals. Most of the literature was in the popular paperbacks emanating from the men’s liberation movement. Moreover, I reviewed the literature on men, I had to face my own psychological issues with sexism, including my relationship with my father and my interactions with both men and women. These emotional issues interfered with my writing since there was confusion, loss, anger, and periodic depression. There were numerous times that I stopped writing completely because I had to process the flood of repressed emotions from the past.

Part of the process was coming to terms with the feeling that I did not really like men that much. Disliking my own gender prompted much soul-searching and then a transformative insight crystallized. I recognized that my dislike of other men really represented what I disliked about myself and my father. Slowly with this one insight, I had less anger and more compassion for men. At the same time, I generated more compassion for myself and my father. I recognized that my problems and my father’s limitations both related to our sexist gender role socialization. After that insight my feelings toward my father and other men changed. I learned that my compassion for men had the capacity to mediate my anger and liberate me from my sexist past. These profound insights helped me see how my gender role journey could be liberating and healing. After this gender role transition (See chapter 5), I began to connect with men I respected and wanted to emulate. There were men that I never met (Gandhi, Robert Kennedy, Teilhard de Chardin, the courageous Martin Luther King), some men that I only met briefly (Daniel and Phillip Berrigan and George Albee), and men in my personal and professional life (Tom Magoon, Delbert Shenkel, Larry Wrightsman, Puncky Heppner, Murray Scher, Joe Pleck, Brooks Collison, and Gary White). These men gave me hope and evidence that the radical-separatists were “off” in describing all men as innate oppressors and misogynists. The list of men and women whom I admired got longer over the years as I met more male colleagues who were Feminists and committed to the psychology of men and women. Many of these colleagues are cited throughout this book.

Conceptual Dilemmas and Confusion

In 1981, Joseph Pleck’s breakthrough book, The Myths of Masculinity was published and this single text became the theoretical foundation for the GRC construct. Pleck described a new model of sex role strain with 10 new propositions about gender roles.

Even with this useful publication, there were many theoretical dilemmas to work out in creating the GRC construct. I got lost in the literature because most of the gender role studies were related to women and there were no integrative reviews about men. Most of the literature in the psychology of women focused on sex differences and androgyny without any mention of men’s gender roles. I was discouraged to not find information about men in the literature and I wondered why this area had been neglected. Based on what I found in the literature, I still did not have concrete answers to the Feminist questions and did not know what to do next.

Sharing GRC at National Conventions Presentations

Pleck’s (1981) sex role strain model was the only theoretically rich conceptualization to expand our knowledge about men and therefore I decided to explore the psychological implications of sex role strain. Pleck’s analysis did not specify what the specific socialization outcomes were for boys and men and therefore the GRC construct became the theoretically defined result of sex role strain. I reached two other conclusions from the literature search: the first was that sexism negatively affects both sexes, and the second was that GRC was a significant mental health issue for both men and women (O’Neil, 1981 a, b, 1982). After integrating the literature, I wanted to create a model that explained why men were sexist, dysfunctional, unhappy, violent, and conflicted because of their socialized gender roles and answer the question “Are men victims of sexism?”.

In 1979, at the ACPA convention in Los Angeles, I gave my first professional presentation on GRC; it was entitled “The male sex role and the negative consequences of the masculine socialization process: Implications for counselors and counseling psychologists” (O’Neil 1979). I remember being nervous about my paper since I had decided to present my work on the GRC and share my vulnerable feelings publicly which certainly went counter to the patriarchal male role. Yet, I felt that the concepts were more valid if they were owned and personalized. The response to my vulnerability was positive and I felt a new kind of strength and energy.

In 1980, I organized a symposium at the APA convention in Montreal on men, one of the first symposia on men in psychology. In the middle of presenting my first GRC model, there was a sudden and unsolicited rush to the front of the room by dozens in the audience to get my paper. We were all stunned by this spontaneous burst of energy. I left the convention convinced that this topic moves people in special ways.

Publication of the First Conceptualizations 1981-1982

The outcome of my literature searches was three published papers (O’Neil, 1981a, 1981b, 1982) and the development of the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS, O’Neil et al., 1986) and the beginnings of the GRC research program that is summarized elsewhere (http://jimoneil.uconn.edu). One paper published in The Counseling Psychologist had an elaborate conceptual model and listed 18 psychological conflicts and 26 effects of men’s rigid and sexist gender role socialization. One year later, the Playboy Magazine published a critique of the listing of the 18 conflicts and 26 effects with the mocking title: “So You Think You’ve Got Problems, Fella”. The brief article read like this:

Changes in sex roles seem to be a growing cause of stress among men. Sexuality Today recently published a list of common conflicts prepared by James M. O’Neil a University of Kansas psychologist. Just in case you think you have nothing to worry about, here is a partial list of O’Neil’s selections: fear of femininity, fear of emasculation, fear of vulnerability, fear of failure, homophobia, limited sensuality, restrictive and affectionate behavior between men, treating women as inferior and as sex objects, low self-esteem, work stress and strain, restrictive emotionality, restrictive communication patterns, obsession with success and achievement, socialized power needs that restrict self and others, socialized competitiveness that restricts self and others, socialized dominance needs that restrict self and others. We recommend that you clip this list, carefully fold it and keep it in your wallet for the next time someone asks you what is bugging you.

I was initially irritated that three years of my work on men was reduced to a joke and a denial about men’s gender role problems. This reaction to my work had deeper meaning than a repudiation of my scholarship. This devaluation of my work was more evidence that GRC was threatening to the status quo and therefore I concluded it was important and should be pursued vigorously.

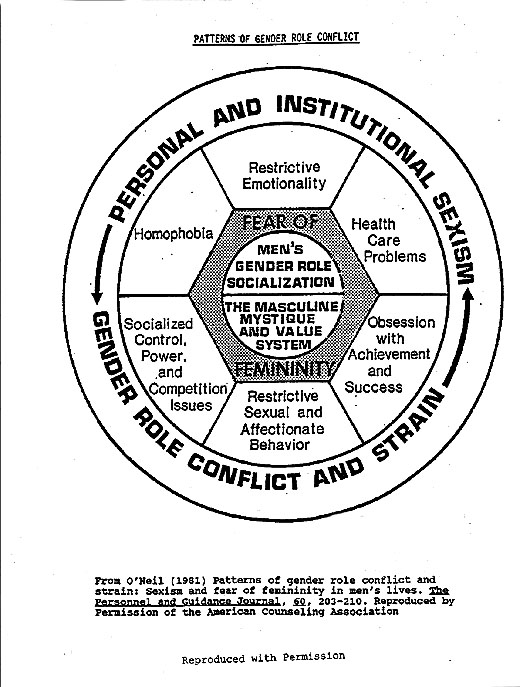

To simplify the long list of men’s problems, I created a conceptual model that captured as many of these conflicts as possible (O’Neil, 1981, 1982). The model implied that men’s gender role socialization and the values of the Masculine Mystique are all related to the fear of femininity. The six patterns of GRC were hypothesized to relate to the fear of femininity and men’s gender role socialization. The patterns of GRC included: restrictive emotionality, health care problems, obsession with achievement and success, restrictive and affectionate behavior, socialized control, power, and competition issues, and homophobia. These six patterns were hypothesized to result from both personal and institutionalized sexism and were my early attempt to operationally define men’s GRC.

The Mentor: Larry Wrightsman Makes the Real Difference

Around the same time, I was sharing my work with Dr. Lawrence Wrightsman, an eminent social psychologist at the University of Kansas. He liked the models and he surprised me when he said “they could have far-reaching impact like the androgyny models and measures like the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) and Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ)”. I was receiving critical feedback about my ideas from everyone and so Larry Wrightsman’s supportive comments were like buoys for me. His confirmation and support was critical to my ongoing process. This one man’s support of my ideas made all the difference with the development and ultimate success of the GRC research program. As you can expect, I am very grateful to Larry for changing my career and life with his generous help and support.

Like all good mentors, Larry challenged me. He said the ideas were important but “they would have minimal impact, meaning a “short shelve life”, without empiricism on the six patterns of GRC.” Specifically, he challenged me to develop an empirical measure of the six patterns of GRC. I was becoming a decent clinician and effective professor, but had no real experience developing a psychological scale. After some resistance on my part, I decided to learn about more test construction and developed the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS). I knew from my clients and from my own life that men experienced GRC but in the psychological sciences, empirical data and scientific tests are needed to promote your theoretical constructs. With another grant from the university and the gracious help of Nancy Betz at Ohio State University, the GRCS was developed and psychometrically tested. We analyzed the data and four patterns of GRC emerged from the factor analyses and the reliability tests. We submitted the scale to Sex Roles and it was published in 1986 (O’Neil, Helms, Gable, David, Wrightsman, 1986).

The Mid and Late 1980’s

During the 1980s’, I gave 18 presentations on the model at 12 different conventions to recruit others to use the GRCS and gather feedback on the GRC construct. From 1984 to 1990, only five dissertations used the scale, and just one paper, Glenn Good’s landmark study on help seeking was published in the literature (Good, Dell & Mintz, 1989). I remember wondering why men’s problems were not of interest to the mainstream counseling and psychology professions. I concluded that the time was not right and this “upstream battle” was occurring because no discipline existed to promote the psychology of men.

The 1990’s were a time when GRC began to receive more attention and critiques. Betz and Fitzgerald (1993) described the GRC research as influential in explaining the restrictiveness of men’s gender roles but cited numerous limitations to the GRCS and the overall research in the psychology of men. Based on this critique, I teamed up with Dr. Glenn Good at the University of Missouri- Columbia and we presented an APA symposium for 17 consecutive years from 1991 to 2008. Those seventeen years of symposia allowed for over 79 empirical studies to be presented by 70 colleagues or their students. There were other developments that expanded the GRC research program.

I raised questions about men as victims of sexism in 1991 at an APA symposium in San Francisco in front of 100 psychologists (O’Neil, 1991) Moreover, backing off from a meaningful question is something I rarely do and I repeated that it was a necessary and legitimate question. Much of the opposition to the “idea of men as victim of sexism” was based on the politics of gender roles in those early days when the psychology of men was forming. Now, 25 years later, the idea of men as victims of sexism has evolved into the concept of gender role trauma strain (O’Neil, 2008; Pleck, 1995) that is developing in the psychology of men. There is a growing recognition that sexism can be victimizing and traumatic, not just for girls and women, but also for boys and men.

In 1995, the first major summary of GRC studies was summarized in Ron Levant’s and William Pollack’s book The New Psychology of Men (O’Neil, Good, & Holmes, 1995) and thanks to Jim Mahalik at Boston College and Clara Hill at the University of Maryland, a special section of the Journal of Counseling Psychology was devoted to men’s GRCin 1995. The GRC research web page ( http//web.uconn.edu/joneil/) was created in 1998 and summarized the 100 studies that have been completed and provided researchers with a quick but comprehensive way of understanding the GRC paradigm. In 1999, the GRC theory was used to conceptualize men’s violence against women with an elaborate model and 15 assumptions (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). In 2005 an adolescent version of the GRCS was published (Blazina, Piseco, & O’Neil, 2005) and in 2012 a short form of the GRCS was created (Wester, Vogel, O’Neil, & Danforth, 2012). These new scales gave the GRC research study more comprehensiveness and utility (See Chapter 4). From 1995 to 2005, the GRC empirical studies increased significantly from 65 to over 230 studies. In 2008, a summary of the 233 studies completed was published as a special issue of the Counseling Psychologist (O’Neil, 2008 and See chapter 7). Currently, there are over 350 studies on men’s GRC.

Giving Credit Where Credit Is Deserved

I take credit for developing the GRC research program over the years but the real credit goes to the hundreds of researchers and their mentors who actually did the research. Table 1 lists the many colleagues and friends that have significantly contributed over time to the GRC research program. The list is long and hopefully I have not missed anyone who made significant and long term contributions. The references in this book also identify many others that have also significantly contributed to the GRC research program. This list and the references demonstrate one of my strong professional beliefs: Individual achievement and success is usually not a solo activity, but occurs through the efforts of many others who contribute to our projects. Those colleagues mentioned throughout the book and deserve full recognition for their many contributions to the GRC research program over the last 30 years.

What did I learn from my gender role journey that I can pass on to future researchers? First, women Feminist taught me that good intentions do not make you credible; it is your actions and advocacy that count. Second, research can significantly challenge the status quo and your colleagues; if you are doing anything important there will be negative reactions, resistance, and threat. Additionally, doing research can promote your personal growth and connect you to exciting people who share your goals, mission, and vision. Furthermore, researching a new topic brings confusion and ambiguity and persistence is required so that the new concepts can be operationalized. When there is no resolution conceptually, create your own ideas and be ready to measure and defend them. I also learned that telling your truth and being personally vulnerable are credible professional roles that can activate both confrontational and supportive forces; therefore be ready for all kinds of reactions to your work. With theory, developing psychological models from the literature can be exciting and when they are published colleagues pay attention. Also, mentors really matter and can change your life as was the case when working with Larry Wrightsman. I also learned that patience, effort, and national networking are required to develop a research program. Finally, always give credit to those who deserve it (See Table 1). Whatever we achieve it is usually not just about our personal accomplishment, but because of the efforts of many others who have given their time, effort, and special contribution to our cause.

Table 1 Researchers and Colleagues Who Made Considerable Contributions to the GRC Research Program

______________________________________________________________________________

| Glenn Good | University of Florida |

| Jim Mahalik | Boston College |

| Chris Blazina | Tennessee State University |

| Gary Brooks | Baylor University |

| Stewert Piesco | University of Houston |

| Matt Breiding | Center for Disease Control |

| David Smith | University of Notre Dame |

| Will Liu | University of Iowa |

| Ron Levant | University of Akron |

| Aaron Rochlen | University of Texas |

| Jay Wade | Fordham University |

| Paul(Puncky) Heppner | University of Missouri |

| Mary Heppner | University of Missouri |

| Ryon McDermott | University of Houston |

| Bonnie Moradi | University of Florida |

| Phil Amato | Salem State University |

| Dawn Syzmanski | University of Tennessee |

| Jon Schwartz | University of New Mexico |

| John Robertson | Renewal Center, Lawrence, KS. |

| Don McCreary | York University |

| David Tokar | University of Akron |

| Jim Rogers | University of Akron |

| Robert Rando | Wrights State University |

| Jay Kim | Seoul, South Korea |

| Chris Kilmartin | Mary Washington University |

| Cisco Sanchez | University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee |

| Ann Fischer | Southern Illinois University |

| Matt Englar-Carlson | California State at Fullerton |

| Joe Pleck | University of Illinois |

| Robert Carter | Columbia University |

| Sam Cochran | University of Iowa |

| Fred Rabinowitz | University of Redlands |

| Will Courtenay | Independent Practice, Berkley, CA |

| Marty Heesacker | University of Florida |

| Andy Horne | University of Georgia |

| Murray Scher | Private Practice Greensboro, TN |

| Jesse Steinfeldt | Indiana University |

| David Vogel | Iowa State University |

| Joel Wong | Indiana University |

| Michael Addis | Clark University |

| Carolyn Enns | Cornell College |

| Aaron Blashill | Harvard University |

| Michele Harway | Antioch University |

| Roberta Nutt | University of Houston |

| Mark Kiselica | College of New Jersey |

| Holly Sweet | MIT |

| Louise Silverstein | Yeshiva University |

| Stephen Wester | University of Wisconsin Milwaukee |

Background and History of GRC Construct (2012)

Background & History of GRC Construct

TAKEN FROM:

Twenty Years of Gender-Role Conflict Research: Summary of 130 Studies

James M. O’Neil, Ph.D.

Department of Educational Psychology

U Box 2058 University of Connecticut

Storrs, Connecticut 06269

(860-486-4281) Jimoneil1@aol.com

Presented In Symposium J.M. O’Neil & G. E. Good (Co-Chairs) Gender-Role Conflict Research: Empirical Studies and 20 Year Summary. Presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Chicago, IL, August 23, 2002.

In 1979, while at the University of Kansas, I wanted to create conceptualizations that explained why men were sexist, dysfunctional, unhappy, and conflicted because of their socialized masculinity. I reviewed the literature on men and masculinity over a three-month period. There was not much scholarly literature on back in those days. Now it would take three years to review the disciplines of Men’s Studies and the new psychology of men. In the 1970’s, there were only a handful of men in the United States who were investigating men’s problems with their gender roles (Warren Farrell, Herb Goldberg, Joe Pleck, Puncky Heppner, Murry Scher, Tom Skovholt, Bob Brannon). I was eager to meet these men and read what these early Men’s Studies scholars were writing. I wanted to join the discussion.

There was very little support in my university setting in the late 1970’s when I began to explore men’s gender role conflicts. Some thought I was gay because I was “interested” in men. Others were threatened because I was exposing the patriarchal system that enslaves us all. Women had mixed reactions to my ideas. Some radical feminists dismissed me without even any dialogue. More moderate Feminists, who were able to get past their anger at men, thought there might be some value in men studying themselves. Yet, even these Feminists wondered whether I was trying to justify men’s sexism and explain away men’s violence against women. The opposite was true: I wanted to really understand the sources of men’s sexism and violence against women. Those were lonely and difficult days for me, not only for these political reasons, but because I was starting my own gender role journey, discovering my own pain from my sexist socialization.

I worked out some of my personal pain by reviewing the literature on men and creating conceptualizations. I wanted to explain why men were violent, interpersonally rigid, sexist, homophobic, unemotional, and unhappy with themselves.

Theoretical History of the Gender Role Conflict Construct

From 1978 to 1979, I synthesized all that had been written on what was then called the men’s liberation literature. In 1980, I submitted my summary to The Counseling Psychologist and to my surprise, they accepted it. The paper was titled: “Male sex-role conflicts, sexism, and masculinity: Implications for men, women, and the counseling psychologists” (O’Neil, 1981). This paper was my synthesis of what I learned from my three month review of the men’s literature. Two figures were published that summarized my synthesis including: 1) the early conceptual model of men’s gender role socialization, and 2) a list of men’s problems that emanate from men’s gender role socialization. Figure 1 below was my overall summary of the issues.

As you can see from this figure, I concluded that men’s socialization is an interaction of environmental and biological factors that produce certain masculine values that I labeled the Masculine Mystique. Using Joe Pleck’s recent concepts (Garnets & Pleck, 1979; Pleck, 1981), the entire socialization process was labeled as sex role strain and conflict. The following year, I changed the term sex role strain/conflict to gender role conflict based on Unger’s (1979) differentiation between sex and gender. I went on to theorize that two major outcomes of the masculine socialization process included: 1) control, power, and competition issues, and 2) restrictive emotionality. The paper enumerated the gender role conflict issues across men’s interpersonal, career, family, and health lives. (See Figure 1 for details)

Finally at the end of the paper, I enumerated the psychological conflicts and effects of men’s rigid and sexist gender role socialization (See Table 1). I was hoping that these lists would: 1) sensitize psychologists to

Sex-role patterns and conflicts and their effects

how men’s gender role socialization could be therapeutic issues, and 2) promote more research on men and their masculinity. These two lists became the basis for hypothesizing the original six patterns of gender role conflict.

Six Patterns of Gender Role Conflict

To simplify the long list of men’s problems, I created a model that captured as many of these conflicts as possible. The model is shown below:

As you can see men’s gender role socialization and the values of the Masculine Mystique are in the center of this diagram and all relate to the fear of femininity. The six patterns of gender role conflict were hypothesized to relate to men’s gender role socialization. The patterns of gender role conflict included: restrictive emotionality, health care problems, obsession with achievement and success, restrictive and affectionate behavior, socialized control, power, and competition issues, and homophobia. These six patterns were hypothesized to result from both personal and institutionalized sexism and were my theoretical attempt to operationally define men’s gender role conflict.

At that time, I was sharing my work with Dr. Larry Wrightsman, an eminent social psychologist, at the University of Kansas. He liked the models and said that they could have far reaching impact. I was getting a lot of resistance and critical comments from the men in my setting to my ideas and so working with Larry Wrightsman was like a buoy. His confirmation and support was critical to my ongoing process. Like all good mentors, he challenged me. Specifically, he challenged me to measure the six patterns of gender role conflict empirically. I was a decent clinician and becoming a good teacher, but never saw myself as a constructor of a psychological scale.

After some resistance on my part, I decided to learn about test construction and developed the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS). I knew from my clients and from my own life that men experienced gender role conflict. But in the psychological sciences, you need empirical data and scientific tests to promote what you believe is the truth. In 1986, the Gender Role Conflict Scale was published in Sex Roles and made available to researchers. This is how the gender role conflict research program began nearly 25 years ago.

Men’s GRC: Personal Reflections and Overview of Recent Research 1994-1997

Published in 1997 in SPSMM Bulletin, Vol 3 (#1) pp. 10-15

James M. O'Neil, Ph.D., School of Family Studies, University of Connecticut,

Glenn E. Good, Ph.D., Department of Psychology, University of Missouri-Columbia

Men's Gender Role Conflict: Personal Reflections and Overview of Recent Research (1994-1997)

We appreciate the invitation to summarize the gender role research program for member of SPSMM. We have collaborated on this research program since Glenn's dissertation in 1986. We have grown immensely from our work together and created a deep fondness which is difficult to put into words. Moreover, the research program has brought us in contact with hundreds of students and colleagues across the country over the last 15 years. We are fully indebted to the 80+ colleagues who have conducted research on gender role conflict. Their hard work has made gender role conflict a meaningful area of scholarly inquiry and professional dialogue. In this brief article, we discuss our research journey over the years and summarize 24 studies that have used the Gender Role Conflict Scale from 1994 to the present. A summary of 35 studies from 1983-1993 is available elsewhere and therefore will not be repeated here (see O'Neil, Good, Holmes, 1995 specifically in Ron Levant's and Bill Pollack's book, The New Psychology of Men (Basic Books, 1995).

Creation of the Gender Role Conflict Construct: Jim's Process

The gender role conflict construct was created in the late 1970's when I was researching the sources of sexism in women's lives. I knew there was widespread sexism, discrimination, violence against women but could not explain why men were sexist. I began to read the Men's Movement literature, particularly the writings of Joe Pleck, Bob Brannon, Warren Farrell, Herb Goldberg, Jim Harrison, to name just a few. These authors gave me hope that a new, nonsexist, definition of masculinity could be created that might decrease sexism between men and women. On a personal level, I was just beginning to face my own sexism and gender role conflict issues. I was regularly confronted by some radical Feminists who believed that all men were oppressors and exclusively blamed all men for the widespread sexism in our society. These were difficult and lonely days for men who were trying to understand the women's movement and men's part in women's oppression. Verbal attacks on men were very frequent and unpleasant. Most of us were on the defensive because we had very few answers to the many good questions that Feminists were asking.

I knew that there must be some psychological, familial, or political reason why men were sexist. It seemed just a little more complex than reducing all men to innate oppressors and misogynists. I needed factual information and concepts about sexism and men's gender role socialization to respond to the questions being asked.

To deal with my knowledge gap, I reviewed the popular and social science literature on men. Back in those days, you could read everything that existed on men's liberation in a couple of months. The social science literature on men was very limited. Nowhere in the literature was there operationally defined, empirically proven, concepts that explained men's conflict with their gender roles. Linda Garnent's and Joe Pleck's sex role strain model was the only scholarly paper that conceptualized sex role strain (Garnets & Pleck, 1979).

Reviewing the literature stimulated a frank assessment of my own personal gender role problems and sexism. It was impossible to read the men's liberation literature in the 1970's without asking some pretty significant issues about one's own gender role conflict. I remember during my reading, getting depressed, anxious, and saying: This stuff is about me and my life!.

From all of this, came an increased energy and commitment to vigorously pursue men's issues personally and by presenting ideas at national conferences. I wanted to see what the reactions might be and create a network of colleagues to work on men's issues.

I got started with this networking when Murray Scher invited me to present my first paper on men at the 1979 ACPA convention in Los Angeles. Working with Murray and a handful of other men, we created the ACPA Standing Committee on Men. This committee was the springboard for convention presentations and publications. The most notable presentation was at the 1980 APA convention in Montreal where we presented the symposium Sex Role conflicts, sexism, masculinity: Psychological implications for counseling psychologists (O'Neil, Skovholt, Scher, Birk, Hanson, Collison, 1980). On the last day of the convention, we had 70 psychologists in the audience listening to six papers on men's sex role conflict. There was a special stir of unusual excitement, tension and energy in the room. In the middle of one of the presentations, the presenter casually mentioned that he had brought his paper to disseminate at the end of the symposia. Spontaneously, there was a storm of people frantically rushing to the front of the room to grab the paper. This frenzy totally disrupted the symposium for at least 10 minutes. After that reaction, there was little doubt in my mind that gender role conflict was a relevant topic that would eventually be of interest to psychology!

I set my goal of having three theoretical papers published on gender role conflict in major journals or books (O'Neil, 1981a, 1981b; 1982). After that, my mentor at that time, Professor Larry Wrightsman, an eminent social psychologist who liked the gender role conflict construct, challenged me to empirically assess it through a quantitative measure. I was reluctant at first, not having much test construction background and knowing it would be difficult psychometric work. With a grant from the University of Kansas and Joe's Pleck's (1981) recently published sex role strain model in hand, we began to develop the Gender Role Conflict Scale in early 1981. The scale was finally published five years later in the journal Sex Roles (O'Neil, Helms, Gable, David, Wrightsman, 1986)

Glenn's Experience with the Gender Role Conflict Scale

As an undergraduate student in California in the early 1970's, I came in contact with the early writings of the Berkeley Men's Center. I also attended an innovative multimedia presentation on men's socialization developed by Dr. Rick Eigenbrod, then a psychologist at the university counseling center. From this initial exposure to men's issues, I developed an active interest in the processes and consequences of gender socialization as it related to my life, and the lives of my friends, family members, and clients. About a decade later, as a doctoral student with an interest in gender issues searching for a dissertation topic, Dr. Nancy Betz mentioned a new scale (then called the Fear of Femininity Scale) being developed by Dr. James M. O'Neil. With significant trepidation (known only too well by graduate students), I contacted Dr. O'Neil who sounded -- much to my surprise -- pleased by my inquiry! Further, to my excitement, the GRCS operationalized key dimensions of masculine role conflict that were (and remain) of interest to me. However, at that time, I perceived the field of Men's Studies to be clearly outside the range of mainstream psychological research and practice. As I wanted to leave open the option of going into academia (although I planned to be a practitioner), I elected to study men's gender role conflict in relation to mainstream psychological constructs like depression and the utilization of psychological services. In 1988, Jim invited me to present these findings at the APA convention in Atlanta, Georgia. He has been kind enough to allow me to collaborate with him ever since that time.

Gender Role Conflict Definitions and Concepts

A full explanation of gender role conflict theory is found in a recent book chapter (O'Neil et al., 1995). Only the basic definitions and concepts are summarized below. Gender role conflict is a psychological state in which socialized gender roles have negative consequences on the person or others. Gender role conflict occurs when rigid, sexist, or restricted gender roles result in restriction, devaluations, or violations of others or self (O'Neil, 1981, 1982, 1990). Gender role conflict implies cognitive, emotional, unconscious, or behavioral problems caused by socialized gender roles learned in sexist and patriarchal societies. Boys and men experience gender role conflict in situational contexts including when they: 1) deviate from or violate gender role norms (Pleck, 1981); 2) try to meet or fail to meet gender role norms of masculinity; 3) experience discrepancies between their real self-concepts and their ideal self concepts, based on gender role stereotypes (Garnets & Pleck, 1979); 4) personally devalue, restrict, or violate themselves (O'Neil, 1990, O'Neil, Fishman, Kinsella-Shaw, 1987); 5) experience personal devaluations, restrictions, or violations from others (O'Neil, 1990; O'Neil, et al., 1987),; 6) personally devalue, restrict, or violate others because of gender role stereotypes (O'Neil, 1990; O'Neil, et al., 1987).

Early conceptualizations of men's gender role conflict were hypothesized to relate to men's gender role socialization, the Masculine Mystique and Value System, men's fears of femininity, and both personal and institutional sexism. Six patterns of gender role conflict were originally hypothesized as shown in Figure 1. Restrictive emotionality, health care problems, obsession with achievement and success, restrictive sexual and affectionate behavior between men, socialized control power, and competition issues, and homophobia were the original patterns of gender role conflict. These six patterns of gender role conflict were used to generate the Gender Role Conflict Scale.

The Gender Role Conflict Scale

Using the above theoretical concepts, an empirically derived measure was created in the Fall of 1981. Using factor analysis and other statistical procedures, four patterns of gender role conflict received empirical support (O'Neil et al., 1986). These four gender role conflict patterns include: a) success, power, and competition, 2) restrictive emotionality, 3) restrictive affectionate behavior between men, 4) conflict between work and family relations. The Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS) is a 37 item measure that assesses directly or indirectly men's conflicts with the four patterns of gender role conflict mentioned above. Respondents are asked to report the degree to which they agree or disagree with statements, using a six point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (6) to strongly disagree (1). Example of items include: I have difficulty expressing my tender feelings; Making money is part of my idea of being a successful man; Affection with other men makes me tense. The psychometric data on the GRCS is accumulating with common, principle components, and confirmatory factor analyses demonstrating a stable factor structure (O'Neil et al., 1986; Good, Robertson, et al., 1995) and acceptable reliabilities. A complete summary of the scale's psychometrics and development can be found elsewhere (O'Neil et al., 1986; O'Neil, et al.,1995). A complete listing of the studies using the GRCS can be found in a lengthy bibliography that is available upon request (See O'Neil, 1997 in reference list).

Empirical Studies Using the Gender Role Conflict Scale (1994 to Present)

There have been over 70 studies using the GRCS (O'Neil, 1997). We categorized the research over the last the three years into the following gender role conflict research areas: a) men's psychological health, b) men's interpersonal behavior, c) diversity and special groups, d) sexual harassment and assault against women, e) therapist gender role conflict and changing gender role conflict. The following abbreviations of the patterns of gender role conflict will be used through the review: SPC = Success, Power, Competition Issues; RE = Restrictive Emotionality; RABBM = Restrictive Affectionate Behavior Between Men; CBWFR = Conflict Between Work and Family Relations.

Men's Psychological Health and Gender Role Conflict

Six studies have assessed gender role conflict with a variety of psychological health variables. Blazina and Watkins (1996) found that the two patterns of gender role conflict, specifically SPC and RE, related to multiple predictors of students' psychological health. They found that students reporting greater RE had decreased psychological well being including more anxiety, more anger, and greater similarity to personality styles of chemical abusers. Furthermore, they found men reporting SPC issues had decreased psychological well being including more anger and increased of alcohol use. Finally, both RE and SPC issues predicted negative views of seeking help.

Two studies have studied the patterns of gender role conflict and alexithymia of college students. Fischer and Good (1995) found that SPS, RE, RABBM, and CBWFR each significantly contributed to the prediction of men's overall alexithymia and to their ability to talk about (describe) their emotions, even after controlling for socially desirable responding. Shepard (1994 a,b) also found that gender role conflict was associated with men's inability to process feelings. He found that male college students' alexithymia was significantly related to RE, SPC, and RABBM. Shepard's research provides evidence that as gender role conflict increases so does alexithymia.

Two studies have looked at men's psychological stress and patterns of gender role conflict. In the first study to use counseling center clients, Good, Robertson, et al., (1996) found that clients' 1) RE and SPC issues significantly predicted paranoia; 2) RE predicted interpersonal insensitivity and psychoticism; 3) RE and CBWFR predicted depression; and 4) CBWFR predicted obsessive- compulsivity. Van Delft and Birk (1996) found using a sample of men in the military, that psychological distress was significantly related to RE, RABBM, and CBWFR. Breaking their sample into client versus non-client categories, they found that clients had significantly higher levels of RE and RABBM.

Two recent studies provide further support for the hypothesis that depression and gender role conflict are related (Good, Robertson, et al., 1996; Shepard, 1994 a,b). College students' RE and CBWFR significantly predicted depression (Good, Robertson et al., 1996) and Shepard (1994 a,b) found that all four of the patterns of gender role conflict were significantly related to depression. Isolating a depressed subsample, Shepard found that increased levels of gender role conflict were associated with greater pessimism and negativity toward self including self-dislike and self-accusations.

Men's Interpersonal Behavior and Gender Role Conflict

Six studies shed light on men's gender role conflict and interpersonal functioning (Berko, 1994; Brush, Berko, Haase, 1996; Fisher & Good, 1995, Mahalik, 1996; Sileo, 1995). Using Kiesler's interpersonal circle, Mahalik (1996) found college men's gender role conflict significantly correlated with more extreme interpersonal behavior. RE was related to hostile-submissive behavior, mistrust, and being cold, detached, and inhibited. RABBM was related to being both hostile dominant and hostile submissive including such characteristics as mistrust, being cold, detached, inhibited, and submissive. CBWFR related to being submissive, friendly, and hostile. Finally, SPC was related to dominance and hostility.

In the first study assessing adult men's friendships, Sileo (1995, 1996) provides evidence on how intimacy and close relationships may be related to gender role conflict. Negative correlations were found between adult men's intimacy and close relationships and three patterns of gender role conflict. Intimacy and close relationships were negative correlated with SPC, RE, RABBM, and the total gender role conflict score. RE had the strongest negative correlations with intimacy and close male relationships. Higher scores on restrictive emotionality related to lower levels of intimacy and close relationships and lower scores of restrictive emotionality related to greater intimacy and closeness between men. These data are supportive of Fischer and Good's (1995) study that found RE significantly predicted fear of intimacy

Men's gender role conflict and shyness have been researched in two separate studies (Berko, 1994; Bruch, Berko, & Haase, 1996). These researchers found that shyness and related personality attributes were directly associated with men's gender role conflict. RE mediated shyness and instrumentality in predicting self disclosure. Using latent variable research, RE was found to mediate fears about negative evaluations as it relates to shyness.

Mahalik and Cournoyer (1997) have assessed men's gender role conflict and defense mechanisms. Initial data indicates that immature defense mechanism (projection, denial, isolation) are related to gender role conflict. Furthermore, they found that SPC and RE are related to defenses that are turned against others.

Diversity, Special Groups, and Men's Gender Role Conflict

Six studies have assessed special groups of men exploring diversity issues and gender role conflict. Thompson (1995 a, b) found that clients who had experienced sexual abuse reported significantly greater RE and CBWFR than did nonabused clients. She also found a relationship between gender role conflicted clients and 1) experiencing sex guilt, 2) having views of the world as malevolent and threatening, 3) having diminished capacity to establish, develop, and maintain relationships based on mutual love, respect, and concern for others.

Gullickson (1993) found that incarcerated sex offenders scored higher on gender role conflict patterns of RE and lower on SPC than non sex offenders. He also found that sex offenders with greater RE, RABBM, and CBWFR also reported significantly less warm, loving and attentive parents. Using a sample of dual career couple husbands, Mintz and Mahalik (1996) found that traditional husbands reported significantly more SPC than role sharing and participant husbands.

Three studies have looked at minority men's gender role conflict. Wade (1996a) found that different stages of racial identity of African American men were differentially predictive of the patterns of gender role conflict. Men in externally defined racial identity stage, reported one or more patterns of gender role conflict. African American men, having an internally defined racial identity reported no patterns of gender role conflict.

Fragoso (1996) assessed Mexican American men, Mexican immigrant men, and Anglo men. For Anglo men, he found that machismo qualities correlated with total gender role conflict, SPC, RE, RABBM. Depression correlated with overall gender role conflict, SPC, RE, CBWFR. For the Mexican sample, global gender role conflict, SPC, and RE predicted stress whereas RE predicted depression. Machismo, as operationalized in this study, was found not to correlate with gender role conflict. The Mexican sample showed that: 1) acculturation, machismo, and gender role conflict predicted stress, 2) as the level of machismo increases so does the gender role conflict, 3) higher levels of machismo and gender role conflict were associated with increasing levels of stress and depression.

Torres Rivera (1995) assessed Puerto Rican men's gender role conflict and ethnic identity. He found that gender role conflict was unrelated to ethnic identity. Furthermore, using confirmatory factor analysis, he found some construct validity for using the scale with poor Puerto Rican men, but clearly more research is needed.

Wade (1996b) completed an innovative study assessing how men's reference group identity or lack of reference group relates to gender role conflict. Reference group identity was defined as the extent to which males are dependent on a reference group for their gender role self concepts. He found that having no reference group was positively related to RE and CBWFR, but negatively correlated with SPC. Reference group dependent men were significantly related to SPC, RE, RABBM, and total gender role conflict scores. Reference group non dependent men were significantly related to RE, RABBM, and total gender role conflict scores.

Addelston (1995a, 1995b) studied high school boy's gender role conflict in both a single sex and coeducational setting. She found no differences in gender role conflict between boys in the two different settings. She did find some predictors relevant to gender role conflict. Boys who had a more fixed sense of reality, lower self esteem, and more traditional attitudes toward women had higher gender role conflict. Boys who had a more relativistic sense of reality, less gender role conflict, and more positive regard for one's school had more egalitarian attitudes toward women.

Sexual Harassment, Assaults Against Women, and Gender Role Conflict

Four studies have assessed the relationship between men's gender role conflict and sexual harassment or sexual assault against women (Floyd, Van Dillen & Kilmartin, 1994; Jacobs, 1995; Rando, Brittan, Pannu 1994; Rando, McBee, Brittan, Olsen-Rando, Winsted, 1995). Jacobs (1995), using an adult sample of men, found that gender role conflict was significantly related to attitudes toward sexual harassment. Men who reported SPC issues had more tolerant or accepting attitudes about sexual harassment. Three studies have assessed gender role conflict's relationship to men's attitudes and relationship toward women, rape myth acceptance, and self reported sexual aggression against women (Floyd, Van Dillen, & Kilmartin, 1994; Rando, Brittan, & Pannu, 1994; Rando, McBee, Brittan, Olsen-Rando, Winsted, 1995). Three patterns of gender role conflict (SPC, RE, RABBM) were significantly related to hostility toward women, rape myth acceptance, stereotypic views of women, feelings of inadequacy, being demeaned or belittled by a woman (Rando et al., 1994) Furthermore, these researchers found that self-reported, sexually aggressive men reported significantly more overall gender role conflict, (specifically, RE and RABBM), than non sexually aggressive men. Contrary to their earlier work, Rando et al., (1995) found that gender role conflict did not differentiate self reported sexual aggressors from non aggressors. They did find that gender role conflict was significantly related rape myth acceptance, traditional stereotyping of women, negative motivations for sexual acts. Finally, Floyd et al., (1994) found no differences between self reported male assaulters of women and non- assaulters across the four patterns of gender role conflict.

Therapist Gender Role Conflict and Changing Gender Role Conflict

The assessment of therapist's gender role conflict was assessed through an experimental study by Wisch and Mahalik (1996). They found that male psychotherapists with high RABBM made negative clinical judgments when evaluating an angry male homosexual client. This research adds to one other experimental study that suggests that gender role conflicted clinicians may hold stereotypic and homophobic views of men (Hayes, 1985).

Using an experimental design, two interventions were developed to see if gender role conflicts could be changed through structured educational program (Brooks-Harris, Heesacker, & Mejia-Millan, 1996). The patterns of gender role conflict were not significantly changed, but the educational programs were able to change certain attitudes toward men's roles.

AUTHOR'S NOTE:

THREE STUDIES ARE REVIEWED HERE THAT WERE NOT INCLUDED IN THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Jim Mahalik and his students at Boston College completed three studies that were not included in the original SPSMM manuscript and we wanted to briefly review them here. Cournoyer and Mahalik (1995) compared college age men with middle aged men. They found that compared with college-aged men, middle aged men were less conflicted about success, power, and competition, but were more conflicted between work and family responsibilities. They also found significant relationships between gender role conflict and psychological well-being. In a second study, Wisch, Mahalik, Hayes, & Nutt, (1995) hypothesized that men's gender role conflict would predict attitudes towards psychological help-seeking after viewing counseling that focused on either client feelings or client cognitions. Their results indicated that men scoring high on gender role conflict who viewed the session that focused on feelings were least likely to indicate a willingness to seek psychological help compared to men in each of the other three conditions. In a third study, Mintz and Mahalik (1996) examined men's gender role factors ( gender role orientation and gender role conflict) as they contribute to the formation of either traditional, participant, or rolesharing family roles in men. The results indicated that traditional husbands reported greater pressure to be successful, powerful, and competitive compared to rolesharing and participant husbands.

Gender Role Conflict Research Program: Summary

The research reported provides more support for Jim Harrison's (1978) article title: Warning: The male sex role may be dangerous to your health. These studies provide more evidence that gender role conflict indeed has negative consequences for men. The psychological issues associated with gender role conflict have been expanded to new areas including anger, alcohol use, alexithymia, psychological distress including areas of paranoia, psychoticism, and obsessive-compulsivity. The relationship of men's intimacy, depression, and helping seeking behavior to different patterns of gender role conflict adds to earlier studies (O'Neil et al., 1995) suggesting their possible importance to providers of psychotherapy and psychoeducational programs. Three of studies used therapy clients and one study focused on male therapist's assessments of men. These studies move us closer to understanding how gender role conflict may become a therapeutic issue during the counseling process. The research relating men's gender role conflict to interpersonal behavior such as shyness, men's friendships and defense mechanisms, and extreme interpersonal behavior begins to address more specific issues of men. As opposed to the earlier studies (O'Neil et al., 1995), six of the studies used adult samples. Furthermore, the diversity of the samples used with these studies included sex abuse victims, sexual abusers, military men, African-American, Mexican-American, and Puerto Rican men, and highschool men. This kind of broader sampling allows gender role conflict to be better understood beyond the usual college student samples.

There are numerous limitations to the research reviewed here and we have addressed some of the more critical issues elsewhere (Good et al., 1995; O'Neil et al., 1995). There is a need for further psychometric work on the Gender Role Conflict Scale before we can fully understand men's gender role conflict.

Basic research is a good thing in itself, but it is even better when it guides clinical practice, community programming, and public policy. We feel that the research on gender role conflict is beginning to address more salient issues for men and women. Our hope is that the next review of studies will focus even more on gender role conflict as it relates to men's pain across different races, classes, ethnic backgrounds, and sexual orientations. Furthermore, research needs to focus on the therapy process with gender conflicted men and assessing innovative and preventive psychoeducational interventions that transform men's lives. We invite each of you in SPSMM to join in this important research endeavor as we begin to develop an empirical base in the new psychology of men.

References

Addelston, J. (1995a). Gender role conflict in elite independent high schools. (Doctoral dissertation, SUNY Graduate School). New York City, New York.

Addelston, J. (August, 1995b). Gender role conflict in elite independent high schools. In J. O'Neil & G. Good (Chairs), Men's Gender role conflict: Empirical studies advancing the psychology of men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, New York, New York.

Berko, E.H. (1994). Shyness, gender-role orientation, physical self-esteem, and gender role conflict. (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Albany, State University of New York). Dissertation Abstracts International, 55/90, 4100.

Blazina, C. Watkins, C.E. (1996). Masculine gender role conflict: Effects on college men's psychological well-being, chemical substance usage, and attitudes toward help-seeking. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 461-465.

Brooks-Harris, J.E., Heesacker, M., & Mejia-Millan, C. (1996). Changing men's male gender role attitudes by applying the elaboration likelihood model of attitude change. Sex Roles, 35, 563-580.

Bruch, M.A., Berko, E.H. & Haase, R.F. (1997). Shyness and male gender- role conflict: Evidence of direct and mediated relations with dysfunction in interpersonal responses. State University of New York - Albany, Albany, New York. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Cournoyer, R.J. & Mahalik, J.R. (1995). Cross sectional study of gender role conflict examining college-aged men middle-aged men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 11-19.

Fischer, A.R. & Good, G.E. (August, 1995). Masculine gender roles, recognition of emotions, and interpersonal intimacy. In J. O'Neil & G. Good (Chairs), Empirical studies advancing the psychology of men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, New York, New York.

Floyd, K.D., Van Dillen, A.B. & Kilmartin, C.T. (1994). Gender role characteristics and parental relationships of sexual assault perpetrators. Unpublished manuscript, Mary Washington College, Fredericksburg, VA.

Fragoso, J.M. (August, 1996). Mexican machismo, gender role conflict, acculturation, and mental health. In J.M. O'Neil and G.E. (Chairs), Men gender role conflict research advancing the new psychology of men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Garnets, L. & Pleck, J. (1979). Sex role identity, androgyny, and sex role transcendence: A sex role strain analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 3, 270-283.

Good, G. E., Robertson, J.M., O'Neil, J.M., Fitzgerald, L. F., Stevens, M., DeBord, K., Bartels, K. M. & Braverman, D.G. (1995). Male gender role conflict: Psychometric issues and relations to psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 3-10.

Good, G.E., Robertson, J.M., Fitzgerald, L. F., Stevens, M.A., Bartles, K.M. (1996). The relations between masculine role conflict and psychological distress in male university counseling center clients. Journal of Counseling and Development, 75, 44-49.

Gullickson, G.E. (1993). Gender role conflict in sex offenders. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa). Dissertation Abstracts International, 55/05, 2008.

Harrison, J. (1978). Warning: the male sex role may be dangerous to your health. Journal of Social Issues, 34, 65-86.

Hayes, M. M. (1985). Counselor sex-role values and effects on attitudes toward, and treatment of non-traditional male clients. (Doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University). Dissertation Abstracts International, 45/09, 3072.

Jacobs, J. (1996). Psychological and demographic correlates of men's perception of and attitudes toward sexual harassment. (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Southern California). Dissertation Abstracts International 97/05, 117.

Levant, R. F. & Pollack, W. S. (1995). The new psychology of men. New York: Basic Books.

Mahalik, J.R., DeFranc, W., Cournoyer, R. & Cherry, M. ( August, 1997). Gender-role conflict: Predictors of men's utilization of psychological defenses. To be presented In J. M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Gender role conflict research: Implications for the new psychology of men. Symposium to be presented at the American Psychological Association, Chicago, Ill, August, 1997.

Mahalik, J.R., (August, 1996). Gender role conflict in men as a predictor of behavior on the interpersonal circle. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Men gender role conflict research: New directions in counseling men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Mintz, R. & Mahalik, J.R. (1996). Gender role orientation and conflict as predictors of family roles for men. Sex Roles. 34, 805-821.

O'Neil, J.M. (1981b). Patterns of gender role conflict and strain: Sexism and fear of femininity in men's lives. Personnel and Guidance Journal, 60, 203-210.

O'Neil, J.M. (1981b). Male sex-role conflicts, sexism, and masculinity: Implications for men, women, and the counseling psychologist. The Counseling Psychologist, 9, 61-80.

O'Neil, J.M. (1982). Gender role conflict and strain in men's lives: Implications for psychiatrists, psychologists, and other human service providers. In K. Solomon & N.B. Levy (Eds.), Men in transition: Changing males roles, theory, and therapy. New York: Plenum Publishing Co.

O'Neil, J.M. (1990). Assessing men's gender role conflict. In D. Moore & F. Leafgren (Eds.) Men in conflict: Problems solving strategies and interventions. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

O'Neil, J.M. (1997). Bibliography on gender role conflict and the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS). School of Family Studies, U Box 58, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269. (Bibliography available by writing to the above address. Complete information on the Gender Role Conflict Research Program will be on line in my home page after July 1, 1997. My E Mail Address is: oneil@uconnvm.uconn.edu

O'Neil, J.M., Fishman, D.M. & Kinsella-Shaw, M. (1987). Dual-career couples' career transitions and normative dilemmas: A preliminary assessment model. The Counseling Psychologist, 15, (1), 50-96.

O'Neil, J.M., Good, G.E., Holmes, S. (1995). Fifteen years of theory and research on men's gender role conflict: New paradigms for empirical research. In R. Levant & W. Pollack (Eds.) The new psychology of men. New York: Basic Books.

O'Neil, J.M., Helms, B., Gable, R., David, L., & Wrightsman, L. (1986). Gender-role conflict scale: College men's fear of femininity. Sex Roles, 14, 5/6, 335-350.

O'Neil, J.M., Skovholt, T.M., Scher, M., Birk, J., Hanson, G., & Collison, B., (September, 1980). Sex role conflicts, sexism, masculinity: Psychological implications for counseling psychologists. J.M. O'Neil (Chair), Symposium presented at the American Psychological Association, Montreal, Canada.

Pleck, J. (1981). The myth of masculinity. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Rando, R.A., Brittan, C.S., & Pannu, R.K. (August, 1994). Gender role conflict and college men's sexually aggressive attitudes and behavior. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Research on men's sexual and psychological assault of women: Programming considerations. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles, CA.

Rando, R.A., Hill, H.E., & Olsen-Rando, D.R. (August, 1996). Parent-child relationship and college men's gender role conflict. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Men's gender-role conflict research advancing the new psychology of men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Rando, R. A., McBee, S.M., & Brittan, C.S. (August, 1995). Gender role conflict and college men's sexually aggressive attitudes and behavior - II. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Empirical studies advancing the psychology of men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, New York, New York.

Shepard, D.S. (1994a). Male gender role conflict and expression of depression. (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Southern California, Department of Counseling Psychology). Dissertation Abstracts International, 55/06, 1477.

Shepard, D.S. (1994b). Male gender role conflict and expression of depression. Paper presented at the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles, CA.

Sileo, F.J. (1995). Gender role conflict: Intimacy and closeness in male-male friendships. (Doctoral Dissertation, Fordham University). Dissertation Abstracts International, 95/43,62.

Sileo, F.J. (August, 1996). Gender-role conflict: Intimacy and closeness in male-male friendships. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Men's gender role conflict research: New directions in counseling men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Thomson, p. (1995a). Men's sexual abuse: Object relations, gender role conflict, and guilt. (Doctoral dissertation, Adelphi University). Dissertation Abstracts International, 56/06, 3467.

Thomson, P. (August, 1995b). Men's sexual abuse: Object relations, gender role conflict, and guilt. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Empirical studies advancing the psychology of men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, New York, New York.

Torres Rivera, E. (1995). Puerto Rican men, gender role conflict, and ethnic identity. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Connecticut). Dissertation Abstracts International, 56/10, 4159.

Van Delft, C. & Birk, J.M. (August, 1996). Military men's gender role conflict, occupational satisfaction, and psychological distress. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Men's gender role conflict research advancing the new psychology of men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Wade, J.C. (1996a). African American men's gender role conflict: The significance of racial identity. Sex Roles, 34, 458-464.

Wade, J.C. (August, 1996b) Reference group identity dependence: A gender role conflict explanatory construct. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Men's gender role conflict research: New directions in counseling men. Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Wisch, A.F. & Mahalik, J.M. (August, 1996). Male counselor gender role conflict and clinical judgment. In J.M. O'Neil & G.E. Good (Chairs) Men's gender role conflict research: New directions in counseling men, Symposium conducted at the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada. 20 21.

Wisch, A.F., Mahalik, J.R., Hayes, J.A., & Nutt, E.A. (1995). The impact of gender role conflict and counseling techniques on psychological help seeking in men. Sex Roles, 33, 77-89.