- Introduction to Gender Role Conflict (GRC) Program

- Overall Information about GRC- Books, Summaries, & History

- Gender Role Conflict Theory, Models, and Contexts

- Recently Published GRC Studies & Dissertations

- Published Journal Studies on GRC

- Dissertations Completed on GRC

- Symposia & Research Studies Presented at APA 1980-2015

- International Published Studies & Dissertations on GRC

- Diversity, Intersectionality, & Multicultural Published Studies

- Psychometrics of the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS)

- Factor Structure

- Confirmatory Factor Analyses

- Internal Consistency Reliability Data

- Internal Consistency & Reliability for 20 Diverse Samples

- Convergent & Divergent Validity of the GRCS Samples

- Normative Data on Diverse Men

- Classification of Dependent Variables & Constructs

- Authors, Samples & Measures with 200 GRC Guides

- Correlational, Moderators, and Mediator Variables Related to GRC

- GRC Research Hypotheses, Questions, and Contexts To be Explored

- Situational GRC Research Models

- 7 Research Questions/ Hypotheses on GRC & Empirical Evidence

- Important Cluster Categories of GRC Research References

- Research Models Assessing GRC and Hypotheses To Be Tested

- GRC Empirical Research Summary Publications

- Published Critiques of the GRCS & GRC Theory

- Clinically Focused Models, Journal Studies, Dissertations

- Psychoeducation Interventions with GRC

- Gender Role Journey Theory, Therapy, & Research

- Receiving Different Forms of the GRCS

- Receiving International Translations of the GRC

- Teaching the Psychology of Men Resource Webpage

- Video Lectures On The Gender Role Journey Curriculum & Additional Information

Gender Role Journey Theory, Therapy, & Contexts

This file provides information about gender role journey theory, therapy, and research. In this file, all of the gender role journey concepts are defined and how to help people journey with their gender roles in therapy and psychoeducation experiences are discussed. Three video lectures on the gender role journey are provided including the details of the gender role journeys of Frank Sinatra and Marilyn Monroe. The following sections enumerate the basic premises of gender role journey theory, therapy and intervention:

Click each topic below to expand

Gender Role Journey Theory Publications

O'Neil, J. M. & Roberts Carroll, M. (1988). A gender role workshop focused on sexism, gender role conflict, and the gender role journey. Journal of Counseling and Development, 67, 193-197.

O'Neil, J. M., & Egan, J. (1992). Men and women's gender role journeys: A metaphor for healing, transition, and transformation. In B. Wainrib (Ed.) Gender issues across the life cycle. New York: Springer Publishing Co.

O'Neil, J. M., & Egan, J. (1992). Men's gender role transitions over the lifespan: Transformation and fears of femininity. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 14, 306-324.

O'Neil, J.M. (1995). The gender role journey workshop: Exploring sexism and gender role conflict in a coeducational setting (Ed.). Men in Groups: Insights, interventions, psychoeducational work. Washington, D.C.: APA Books

O’Neil, J.M. (2015). New contextual paradigms for gender role conflict: Theory, research, and practice. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 41-77. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

O’Neil, J.M. (2015) My personal gender role journey with the gender role conflict research program. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 29-38. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

Published Research on Gender Role Journey Measure & Construct

Burns, L.R. (2017). The impact of emerging adulthood life events on men’s gender role journey (Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology). Dissertation Abstracts International, 978-13390546346, 2016, 477717-110.

O'Neil, J. M., Egan, J., Owen, S.V., & Murry, V.M. (1993). The gender role journey measure (JRJM): Scale development and psychometric evaluations. Sex Roles, 28, 167-185.

Goldberg, J. & O’Neil, J.M. (1997). Marilyn Monroe’s gender role journey: Promoting women’s development. Journal of College Student Development, 38, 543-545.

Grandi, L., Minton, S., May, J., Tipton, K. (2023). UK men’s experience of the gender role journey and implications for clinicians and mental health services. Psychology of Men and Masculinities.

McDermott, R.C. & Schwartz, J. (2013). Toward a better understanding of emerging adult men's gender role journeys: Differences in age, education, race, relationship status, and sexual orientation. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 14, 202-210.

McDermott. R.C., Schwartz, J.P., Trevathan-Minnis, M. (2012). Predicting men's anger management: Relationship with gender role journey and entitlement. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 13, 49-64.

Mock, J.F. (1995). Influence of gender role journey and balance of power in the marital relationship, on the emotional and spiritual well-being of mid-life married women. Dissertation Abstracts International, 56 (5), 9531244.

O’Neil, J.M. (2000) Review of the Gender Role Journey Measure (GRJM). In J. Maltby, C. Lewis, & A. Hill (Eds.) Commissioned reviews of 250 psychological tests. Credigion, Wales: The Edwin Mellon Press.

O’Neil, J.M. (2015) Gender role journey therapy with men. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 227-248. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

Definition of the Gender Role Journey

A metaphor for the process of examining how gender role socialization experiences effects a person’s life.

The journey involves evaluating thoughts, feelings, and behaviors about gender roles, sexism, and gender role conflict including a retrospective analysis of early family experiences, assessment of one’s present status with gender roles, and a projection of gender roles into the future.

From Chapter 3, p. 48 O’Neil (2015)

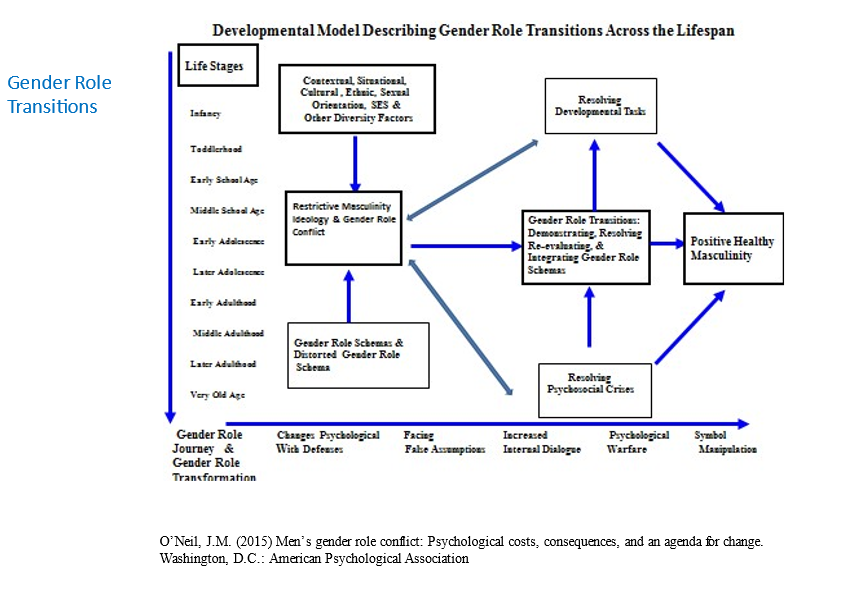

Developmental Model Describing Gender Role Transitions Across the Lifespan

Psychosocial theory provides a vantage point to theorize about gender role transitions and developmental changes in men and boys. Figure 5.1 depicts a developmental model that integrate gender role transitions and GRC with psychosocial theory (Newman & Newman, 2012).

From O’Neil, J.M. (2015). A developmental model of masculinity: Gender role transitions and men’s psychosocial growth. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 79-93. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

As mentioned earlier, psychosocial theory provides a vantage point to theorize about gender role transitions and developmental changes in men and boys. Figure 5.1 depicts a developmental model that integrates gender role transitions and GRC with psychosocial theory (Newman & Newman, 2012). On the left of the figure shows life stages where psychosocial gender related processes are experienced from infancy to very old age. The vertical listing of the stages on the left implies that the processes can occur at any times during life. At the bottom, the journeying with gender roles and the gender role transformation processes are shown. The transformational processes include working with defenses, considering false assumptions, engaging self-dialogue and psychological warfare, and symbol manipulations. The six rectangles in the middle of Figure 1 reflect the complexity of GRC from a developmental perspective in the context of the life stages and psychosocial development.

First, the model in Figure 5.1 indicates that restrictive masculinity ideology and GRC, shown at the left of the figure, are shaped by contextual and situational factors including cultural, racial, ethnic, socioeconomic status (SES), and sexual-orientation indices that ultimately affect psychosocial growth at each life stage. Gender role change occurs because of these factors and a host of others, and GRC is possible at any life each stage. Also affecting restrictive masculinity and GRC are gender role schemas and distorted gender role schemas, also shown at the left of Figure 5.1. As discussed earlier, gender role schemas and their distortions are part of psychosocial development that can result in fears and anxieties about not measuring up to traditional gender role expectations. These schemas and distorted schemas also relate to resolving developmental tasks and psychosocial crises. Restrictive masculinity ideology shown in the middle of the figure is the sum total of all the gender role schemas, distorted gender role schemas, and the contextual, situational, cultural factors that can have a positive or negative effect on the boy or and man’s. life.

The bidirectional (or reciprocal) arrows between restrictive masculinity ideology and GRC and the resolution, respectively, of developmental tasks and psychosocial crises suggest two hypotheses: (a) masculinity ideology and GRC negatively affect the resolution of developmental tasks and psychosocial crises; and (b) the tasks and crises can produce GRC or contribute to restrictive masculinity ideology.

In the middle of Figure 5.1, the working through of the tasks and crises is accomplished through gender role transitions that come about through the action-oriented processes of demonstrating, reevaluating, performing, and integrating gender role schemas. Finally, as shown at the right of the diagram, the effective resolution of gender role transitions, developmental tasks, and psychosocial crises results in psychological health and maturity—what currently is known as healthy/positive masculinity (Kiscelica, 2011; Kisleica & Englar-Carlson, 2010) Previous definitions of healthy masculinity have enumerated male strengths and adaptive and positive aspects of being a man. I extend this definition by describing positive healthy masculinity as full maturation by mastering developmental tasks and resolving the psychosocial tasks and crises across the life cycle. Figure 1 provides an overall framework to discuss developmental assumptions about psychosocial growth in the context of developmental masculinity.

Theoretical Assumptions About Developmental Masculinity: Gender Role Conflict, Gender Role Transitions, and Psychosocial Growth

The table below enumerates theoretical assumptions about how psychosocial theory can be integrated with GRC constructs. A careful reading of these assumptions suggest that gender role transitions exist throughout the life stages and boys and men experience varying degrees of restrictive masculinity ideology and GRC that affects psychosocial development in each developmental period. Numerous contextual and situational factors affect how masculinity ideology and GRC impact psychosocial growth including mastering developmental tasks. Efforts to master the developmental tasks and resolve psychosocial crises can cause GRC. Furthermore, gender role transitions may be necessary to master the developmental tasks and resolve the psychosocial crises. Mastering developmental tasks and resolving psychosocial crises, at least in part, involves changes in gender role values and self-assumptions. Journeying with one’s gender roles is what is needed to resolve gender role transitions and involves demonstrating, resolving, redefining, and integrating gender role schemas related to masculinity and femininity ideologies. Restrictive masculinity ideology and GRC may limit behavioral and emotional flexibility needed to master developmental tasks and resolve psychosocial crises. Distorted gender role schemas about masculinity and femininity may need to be corrected (redefined) to effectively resolve developmental tasks and the psychosocial crises. FOF and homophobia are major inhibitors of men managing gender role transitions, mastering the developmental tasks, and resolving psychosocial crises. Optimal development and positive masculinity are when the developmental tasks and psychosocial crises are resolved and there is positive transition to the next stage of development. Clinician and programmers can use gender role transitions, gender role schemas, and the gender role journey in therapy with men and during psychoeducational interventions.

| Theoretical Assumptions About Gender Role Conflict, Gender Role Transitions, Psychosocial-Developmental Growth |

| 1. Gender role conflict and gender role transitions exist throughout the life cycle. |

| 2. During the life stages, boys and men have varying degrees of restrictive masculinity ideology and GRC that affects psychosocial development of that developmental period. |

| 3. Numerous contextual, cultural, and situational factors affect how masculinity ideology and GRC impact psychosocial growth including mastering developmental tasks and psychosocial growth. |

| 4. Gender role transitions may be necessary to master the developmental tasks and resolve the psychosocial crises. |

| 5. Mastering the developmental tasks and resolving the psychosocial crises are the events that can produce changes in a man’s gender role values and self -assumptions. |

| 6. Resolving gender role transitions related to developmental tasks and psychosocial crises involves demonstrating, resolving, redefining, and integrating gender role schemas related to masculinity and femininity ideologies. |

| 7. Restrictive masculinity ideology and the patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, & CBWFR) may limit behavioral and emotional flexibility and interfere with the developmental tasks and the resolution of the psychosocial crises. (See bi-directional arrow in Figure 1). |

| 8. Efforts to master the developmental tasks and resolve psychosocial crises can cause GRC. |

| 9. Distorted gender role schemas about masculinity and femininity may need correction to effectively resolve developmental tasks and the psychosocial crises. |

| 10. FOF and homophobia can interfere with effectively managing GRT and resolving developmental tasks and psychosocial crises. |

| 11. Optimal development and positive masculinity are when the developmental tasks and psychosocial crises are resolved and there has been full gender role transition, meaning that the changed self- assumptions about gender roles facilitate rather than delay further development. |

| 12. Journeying with one’s gender roles can facilitate gender role transitions and includes recognizing the costs of gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations. |

| 13. The transformation process of journeying with gender roles includes : a) changing psychological defenses, b) facing false assumptions, c) increasing internal dialogue, d) managing psychological warfare, and e) symbol manipulation. |

| 14. Therapists and psychoeducational programmers can use gender role transitions, gender role schemas, and the gender role journey in therapy with men and during preventive interventions |

From O’Neil, J.M. (2015). A developmental model of masculinity: Gender role transitions and men’s psychosocial growth. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 79-93. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

The Gender Role Journey Paradigm and Phases

Another central concept in the GRC research program is the gender role journey. The gender role journey is a metaphor and framework that helps people examine how their gender role socialization, GRC, and sexism have affected their lives (O’Neil & Egan, 1992a). The journey involves doing a retrospective analysis of early family experiences with gender roles, making an assessment of one’s present situation with sexism, and making decisions about how to act in the future. The overall purpose of the process is to evaluate how gender roles and sexism have affected one’s life personally, professionally, and politically and use this knowledge to improve one’s life and society.

Table 1 describes three phases of the gender role journey, which imply change and transitions with gender roles. They are (1) acceptance of traditional roles; (2) gender role ambivalence, confusion, anger, and fear; and (3) personal and professional activism (O’Neil, et al., 1993a). The gender role journey also involves identifying gender role transitions as they occur in life and reexamining gender role schemas (O’Neil & Egan 1992b; O’Neil & Fishman, 1992; O’Neil, Fishman, & Kinsella-Shaw, 1987). The Gender Role Journey Measure (GRJM) was created to help both men and women determine which phases of the gender role journey they identify with (O’Neil, Egan, Owen, & Murry, 1993). Part of the journey is the process of coming to understand how GRC develops in the family and as the result of other socialization experiences in society. Full theoretical descriptions of these phases are found in the following publications: O’Neil, Egan, Owen, Murry, 1993; O’Neil & Egan, 1992 a, b ; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1987; O’Neil, 2015.

click below to expand each section

Table 1 Phases of the Gender Role Journey

| Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles Attitudes and Beliefs |

| In this phase of the gender role journal the man endorses traditional gender role stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. There are male and female roles based on biological imperatives or some other essentialist value system. Men should be in charge at work and in the home and women should provide the primary child care. Men should be strong and not show weakness and women should be more passive and not assertive. There is limited awareness of how sexism can hurt people, a belief that feminist have caused problems between men and women, and no interest in doing anything about sexism and discrimination. |

| Gender Role Ambivalence, Confusion, Anger and Fear |

| This phase of the gender role journey the person is confused about gender role stereotypes has some fear about the journeying with them. There is vacillation between accepting the stereotypes and recognizing they negatively restrict people in relationships. There is fear about questioning or changing gender role stereotypes and the persona needs help with the process. There is anger about sexism but it is not clear why this emotion exists and doesn’t know what to do about. There may be limited outlets for their anger. The more they express their anger about sexism the more conflict they have. Some people in this stage have intense anger because they know that they and others have been victims sexism and restrictive gender role socialization. Anger is pivotal in moving from dysfunctional phase to a functional phase of the journey. Some people believe that staying angry or getting stuck in your anger is counterproductive. Some conclude that the stereotypes are insufficient to build a human identity. Only when anger becomes great is there willingness to take risks of challenging the status quo. |

| Personal and Professional Activism |

| Activism mean changing oneself by integrating the anger and by making commitments to reduce sexism in one’s own life. Activism begins when talking does not work and action is perceived to be a better course to pursue. In this phase the person attempts to live free from restrictive gender role stereotypes and feels an inner strength and power based on rejecting restrictive gender roles and sexism. Their anger, pain, and emotions are used to reduce sexism and raise other people’s consciousness through teaching and other activist agendas. There is the strong believe that they are responsible for reducing sexism and that something can be done to prevent it through activism. Increased self-communication is required to remain in the activism stage. There is greater compassion for self and other people’s gender role journeys. |

| From: O’Neil, J.M. (2015). The contextual paradigms for gender role conflict: Theory, research, and practice. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 41-77. Washington, D.C. APA Books. |

Definition of Gender Role Transitions

Gender role transitions are events in a person’s gender role development that produce changes in his or her gender role identity and self-assumptions. Understanding gender role transitions across the lifespan by journeying with them is one way to understand GRC and the develop healthy-positive masculinity. In the midst of them, men and women demonstrate, resolve, reevaluate, or integrate new or old conceptions of masculinity and femininity—as West and Zimmerman (1998) put it, they are “doing gender” or “redoing gender.” Gender role transitions are hypothesized to relate to mastering developmental tasks, resolving psychosocial crises, and facing dilemmas with maturity. They can produce positive growth or confusion, anxiety, and despair, and failure to resolve them may stimulate GRC and other emotional problems. Four action-oriented processes can occur during gender role transitions, that is, the person can make a concerted effort to demonstrate, resolve, reevaluate, or integrate (in the case of a man) masculinity ideology issues. Each of these is defined below.

The demonstration, resolution, reevaluation, and integration of masculine and feminine values may occur during the normal maturation process. These transitional processes can open up internal parts of the man, expand his self-definition, and promote personal exploration and growth. One of the more vital issues is how these four psychological processes occur cognitively and emotionally with gender role schemas as males face developmental tasks and challenges in life.

Identifying Gender Role Transitions In the Context of Psychosocial Theory

In this section many gender role transitions are listed that relate to developmental tasks and psychosocial crises discussed in psychosocial theory. Table 2 shows the life stages, developmental tasks, and psychosocial crises proposed by Newman and Newman (2012) and specific examples of gender role transitions or tasks related to the transitions. In the first column at the left of Table 2 are listed the ten life stages and, in column two, at least one of Newman and Newman’s developmental tasks corresponding to each. The psychosocial crises for the ten stages are listed in the third column, followed in the fourth by the gender role transitions that are predictable during each period of growth and development. Applying the relationships proposed earlier in Figure 1, we can hypothesize that each developmental task and psychosocial crisis involves one or more gender role transition that is vital to mastering the task and resolving the crisis, and vice versa.

In this way, we can see that issues related to masculinity and femininity are directly related to psychosocial growth. Mastering the developmental tasks and resolving the psychosocial crises is necessary to work through the gender role transitions, and vice versa. In accordance with the definition of gender role transitions, each task and crisis involves some aspect of demonstrating, resolving, reevaluating or integrating masculinity norms and standards. The associations made at each life stage provide a preliminary developmental framework to understand boys’ and men’s gender role socialization over the lifespan in the context of psychosocial development. GRC results when the psychosocial issues (that is, the tasks and crises) are delayed or go unresolved.

| Life Stages, Developmental Tasks, Psychosocial Crises, and Gender Role Transitions | |||

| Life Stages | Developmental Tasks | Psychosocial Crises | Gender Roles Transitions |

| Infancy Birth to 2 |

Attachment | Trust versus Mistrust |

|

| Toddlerhood 2 – 4 |

Fantasy Play | Autonomy vs. Shame/Guilt |

|

| Early School Age 4 – 6 |

Gender Identification | Initiative vs. Guilt |

|

| Middle Childhood 6 – 12 |

Learning Skills Self -Evaluation |

Inferiority vs. Industry |

|

| Early Adolescence 12 – 18 |

Puberty Emotional Development Finding Peer Group |

Group Identity vs. Alienation |

|

| Later Adolescence 18 – 22 |

Autonomy From Parents Choosing Career Path |

Individual Identity vs. Identity Confusion |

|

| Early Adulthood 23 – 34 |

Intimacy – Marriage Child Bearing Early Work – Career |

Intimacy vs. Isolation |

|

| Middle Adulthood 34 – 60 |

Managing Career/Home Maintaining Intimate Relationships |

Generativity vs. Stagnation |

|

| Later Adulthood 60 – 75 |

Accepting One’s Life Redirecting Energy to New Roles |

Integrity vs. Despair |

|

| Very Old Age 75 – Death |

Coping with Physical Changes from Aging Dealing with Death |

Immortality vs. Extinction |

|

From O’Neil, J.M. (2015). A developmental model of masculinity: Gender role transitions and men’s psychosocial growth. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 79-93. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

The Processes of Gender Role Deconstruction

These deconstruction concepts are the nuts and bolts of the gender role journey process that I observed with the 700 students who enrolled in my summer gender role journey workshop from 1984-2007 and who now take this workshop online.

Deconstructing gender roles means telling the truth about sexist assumptions and stereotypes that distort what it means to be fully human, confronting the lies about the rewards of highly sex-typed attitudes and behaviors, and identifying and correcting the myths that men and women are more different than alike (O’Neil & Renzulli, 2013a).

What happens during gender role transitions? There is both the construction and deconstruction of gender roles, masculinity/femininity ideologies, gender role norms and expectancies.

Deconstruction of Gender Roles:

- A critical analysis of destructive gender role stereotypes and the evaluation of unverified sex differences.

- Personal, social, and political realities of personal oppression, discrimination, and social injustice are exposed.

- How race, class, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation affect psychological functioning are explored.

- The negative effects of personal and institutional forms of sexism, racism, classism, heterosexism, ethnocentrism, or any other kind of discrimination in people’s lives is understood.

- How gender roles relate to sex discrimination, emasculation, homophobia, homonegativity, poverty, sexual assault, harassment, emotional abuse, and societal violence is understood.

- The status quo’s investment in sexism is explored by coming to understand how the dominant cultures oppress vulnerable groups including women, people of color, sexual minorities.

- The economics of oppression is recognized by acknowledging that that profits are made when agents of destructive capitalism use sexism and stereotypes to foster injustices and discrimination.

The Personal and Political Dimensions of Deconstructing Masculine Gender

Roles (Chapter 1- pages 13-14, O’Neil (2015)

Convincing mainstream psychology to study men has been difficult because, until the 1980s, patriarchal values dominated psychological theory and research. White males were the normative referent group for research and psychological knowledge during the first eight decades of American psychology. Consequently, the psychology of men is frequently associated with biased studies, sexism, male dominance, the devaluation of women, and with research and theories narrowly defined by sex differences rather than men’s real-life experiences. As will be shown in this book, the new psychology of men is not about these sexist aspects of scientific study.

One explanation of why the psychology of men has been slow to develop is that the issues are both controversial and intensely personal and political. The primary way to understand sexism and GRC is by deconstructing traditional gender roles, a process that has been championed by women feminists in psychology and other disciplines (Enns, 2004; Enns & Williams, 2013). Deconstructing gender roles means telling the truth about sexist assumptions and stereotypes that distort what it means to be fully human, confronting the lies about the rewards of high sex typed attitudes and behaviors, and identifying and correcting the myths that men and women are more different than alike (O’Neil & Renzulli, 2013aq). It involves the critical analysis of destructive gender role stereotypes and the evaluation of unverified sex differences that underlie sexism for both men and women, and it includes examining research evidence about sex differences while resisting the temptation to settle for simple answers to complex human problems—for instance, the superficial “Mars and Venus” explanations of men’s and women’s relationships (Gray, 1989).

Furthermore, the deconstruction of traditional gender roles can reveal the personal, social, and political realities of personal oppression, discrimination, and social injustice. Reaching this deeper level requires analyzing how racial, class, ethnic, religious, and sexual orientation indices affect psychological functioning and making an effort to acknowledge the effects of personal and institutional forms of sexism, racism, classism, heterosexism, ethnocentrism, or any other kind of discrimination on people’s lives. The deconstruction process raises significant questions about how gender roles relate to sex discrimination, emasculation, homophobia, homonegativity, poverty, sexual assault, harassment, emotional abuse, and societal violence. In the course of it, the status quo’s investment in sexism is recognized and confronted by coming to understand how the dominant cultures oppress vulnerable groups, including women, people of color, sexual minorities, immigrants, and even white men. Also acknowledged is the economics of oppression, which is understood by explaining that profits are made when “destructive capitalism” uses stereotypes to foster injustices and discrimination.

On a personal level, the deconstruction of gender roles can challenge ethnic, familial, religious, or cultural mores related to masculinity and femininity, which can threaten personal identities and violate family values and even invalidate established world views. In this context, the personal becomes political very quickly, and polarization and strong emotions can arise. On a societal level, the oppressiveness of the status quo becomes very visible and obvious when these issues are illuminated. In short, the assessment of patriarchal structures is unsettling and can destroy the illusion that everything is okay in men’s and women’s lives. It compels us to admit that men are troubled, and the entire social system is vulnerable and unstable. Activists who expose these realities threaten dominant power brokers who profit from the inequities. They also threaten regular people whose lives are based on traditional gender roles.

Given the complexity and volatility of the issues, many people find the deconstruction of gender roles overwhelming and retreat from the realities and inevitable problems it exposes. Over the decades, even activists have tired with the struggle as opposition to and support for feminism have ebbed and flowed. In this book I try not to sidestep these critical issues, but to connect them to GRC and to men’s and women’s gender role journeys (O’Neil & Egan, 1992 a, b; O’Neil, Helms, Gable, David, & Wrightsman, 1986).

While vulnerabilities and insecurities do arise from the deconstruction of gender roles, eventually a single truth emerges: outdated, stereotypical, and restrictive gender roles do not provide the foundation for equality between the sexes; rather, they provide the basis for sexism and other forms of oppression that cause violence and social injustices. As all mental health professionals know, social injustice causes poverty and serious psychological problems for men, women, and children and is therefore a critical issue for psychologists and other caring professionals to address.

From O’Neil, J.M. (2015). A call to action to expand the psychology of men. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 9-28., Washington, D.C. APA Books.

Correcting and Understanding Gender Role Schemas and Distorted Gender Role Schemas

Personal changes and modifications in gender role values are not completed in a vacuum and what thoughts and feelings get demonstrated, resolved, re-evaluated, or integrated is the critical question. In order for boys and men to complete gender role transitions, there is usually cognitive and affective processes operating that facilitate the completion of the transition. The transitions are experienced in the context of certain gender role schemas.

Gender role schemas are cultural definitions of maleness and femaleness that organize and guide an individual’s perception of masculinity and femininity based on sex and gender roles. The schema is related to the person’s self-concept and is used to evaluate his or her personal adequacy as male or female. The issue of personal adequacy to meet the demands of restrictive gender roles schemas is part of the gender role strain and conflict that both men and women experience. Gender role schemas are considered when boys or men demonstrate, resolve, reevaluate, or integrate masculinity and femininity during gender role transitions. On a cognitive and affective level, gender role schemas are what men struggle with during gender role transitions.

Many men have learned gender role schemas that are distorted and based on sexist stereotypes. Distorted gender role schemas are exaggerated thoughts and feelings about masculinity and femininity as applied to major life issues. The distortion occurs because of perceived or actual pressure to meet stereotypical notions of masculinity, resulting in fears and anxieties about not measuring up to traditional gender role expectations. These distorted gender role schema are part of the man’s restricted masculinity ideology that produce GRC and maybe contribute to precarious manhood (Vandello & Bosson, 2003; Vandello, et al., 2008).

What schemas do men struggle with during gender role transitions? What schemas need to demonstrated, resolved, reevaluated, and finally integrated. What schemas get distorted and contribute to GRC? Table 3 shows some of these gender role schemas and their distortions. These schemas are the gender related themes that boys and men process during gender role transitions.

| Definitions of Gender Role Schemas and Distorted Gender Role Schemas | |||

| GENDER ROLE SCHEMAS | DEFINITIONS | DISTORTED GENDER ROLE SCHEMAS | |

| 1 | SUCCESS | Attaining wealth, favor, or eminence | Success is a measure of my manhood |

| 2 | ACHIEVEMENT | Successful completion and accomplishment brought about by resolve, persistence, or endeavor | I have to achieve regularly to feel good as a man |

| 3 | COMPETENCE | Having adequate ability, qualities, and capacity to function in a particular way | I can never fail as a man |

| 4 | CONTROL | Regulating, restraining and having others or situations under one’s command | I have to always be in control to feel secure |

| 5 | POWER | Obtaining authority, influence, or ascendancy over others and one’s environment | Without my power, I am less of a man |

| 6 | COMPETITION | Striving against others to gain something and establishing one’s superiority or skill | I have to always win to feel good |

| 7 | STRENGTH | Having capacity for endurance physically, emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually | I should never show weakness |

| 8 | PERSONAL WORTH | Being valued by others and to value self | I have to prove my personal value over and over again |

| 9 | PROVIDER ROLE | Assuming economic responsibility for family | I am less of a man if I cannot take care of my family |

| 10

|

PERSONAL COMMUNICATION | Verbal and nonverbal ways of interpersonal exchange | The less said, the better |

| 11 | WOMEN’S AND MEN’S WORK | Perceptions of appropriate work roles for each sex | Men should work, women should take care of the kids |

| 12 | HEALTH CARE | Recognition of factors that maintain a healthy life | I don’t ever have to go to the doctor |

| 13 | FATHERHOOD | Parental role with sons and daughters | I have the ultimate say in the family |

| 14 | SEXUALITY | Understanding sexual needs, attitudes, values, and behaviors | Performance is a measure of my manhood |

| 15 | INTIMACY | Understanding intimacy needs, attitudes, values, and behaviors | Getting close emotionally is risky and can cost me |

| 16 | EMOTIONALITY | Understanding of and ability to express emotions | Emotions are feminine and therefore not to me |

| 17 | HOMOSEXUALITY | Sex between people of the same sex | Being gay is disordered, morally wrong and bad for society |

| 18 | DEPENDENCE | A need or reliance on others | I don’t need anybody; I can do everything on my own. |

| 19 | VULNERABILITY | Feeling of weakness | Never show any weakness because you will be taken advantage of by someone. |

| 20 | PERFORMANCE | Being able to demonstrate your skills | If I don’t perform every time, I am loser. |

Gender Role Transformational Processes

The critical question is how to journey with gender roles, resolve gender role transitions, and effectively redefine distorted gender role schemas to enrich one’s life. This process is challenging and relates to transformations (See Figure 3 at the bottom). Gould (1978, 1980) defined transformation as expanding one's self-definition to produce inner freedom without conflict or anxiety, thereby internalizing a maximum sense of personal security. Likewise, gender role transitions can produce a redefinition of masculinity and femininity, decreased gender role conflict, greater freedom with gender roles, and increased self-confidence. Gould posited numerous properties of the transformation process that have relevance to explaining the internal dynamics of gender role transitions and the gender role journey including a) changes in psychological defenses, b) facing and dealing with false assumptions, c) increases in internal dialogue with self, d) internal psychological warfare. Each of these is elaborated on in the context of men’s gender role transitions.

When people struggle to change their fundamental conception of gender roles, the defensive structure of their personality may need alteration to foster more functional and expansive ways to live. The past defenses may no longer function fully for the person and new psychological mechanisms are needed to enhance coping and promote the transformation. Defensive structures vary greatly, but repression, projection, regression, and reaction formation are quite common. The essence of most defense mechanisms is the inability to face emotions and feelings and therefore an emotional leveling or shutdown. Emotions relevant to one’s gender role identity can be intellectualized, denied, represses, and projected in anger and hostility towards others. Therefore, gender role transitions may require a fundamental change in people’s psychological defense system and new ways of experiencing deep emotions as part of the gender role journey.

Furthermore, false assumptions or illusions about gender roles may help maintain a defensive posture. Before the transformation occurs, false ideas about gender roles from childhood consciousness usually establish the functional boundaries of self-definition. These functional boundaries are maintained until the false ideas are disconfirmed and disbelieved. For example, beliefs that real men always have to be strong, successful, powerful, unemotional, and in control are gender role illusions that reflect societal stereotypes. These stereotypes are usually internalized at an early age to establish men’s and women’s gender role identity. Willingness to challenge these false ideas may depend on obtaining new information, deep emotional awakenings, and political awareness that sexism violates women and men in a capitalist society.

More important, gender role transitions stimulate an internal dialogue in the context of the new, emerging gender role identity. This internal dialogue may inhibit transformation, since the false ideas may produce anxiety and feelings of psychological regression. Usually, the false self-assumptions prohibit the gender role transition process and maintain personal anxiety and gender role conflict. If men and women can face these false assumptions, they can begin the internal dialogue necessary to deconstruct gender roles and prompt gender role change.

This internal dialogue may bring about psychological warfare between the person and their external world or between the old self and the new, emerging identity. During gender role transitions, “enemies” of the self are sometimes identified from the intense emotions, especially anger and fear. Yet, who these enemies are may be unclear. Women, other men, parents, children, and institutional structures may be targeted as the enemy to be attacked or avoided. Men and women may identify a weakened sense of themselves as the enemy, in terms of their self-imposed restrictions, devaluations, and personal limitations. Identifying the “enemy within” usually produces low self-esteem, anxiety, anger, and defensiveness that destabilize the person.

Adding to Gould’s definition of transformation, gender role transitions may require a new manipulation of symbols and the use of metaphors for change and healing. Instrumental outcomes such as success, status, and power can be replaced with transformative myths, metaphors, symbols, and images. Past interest in mythology (Campbell, 1988; Johnson, 1986) represents an evolving person’s desire to use symbolic representation to find greater meaning in life. Johnson (1986) indicated that the “most rewarding mythological experience you can have is to see how it lives in your own psychological structure” (p.x). Myths offer us the truth about ourselves and dispel the hardened illusions that we have based our lives on.

The use of metaphors, images, and symbols gives men and women an opportunity to redefine their gender perspectives. In my gender role journey workshops (See Chapter 13; O’Neil, 1996; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988), I have seen the power of symbols and metaphors in promoting transformation. For example, if the symbols (i.e., stereotypes) of power and control have been rigidly internalized as money, status, authority, and power over others, then a new conceptualization of power and control can be developed. Power could be redefined as the symbolic and real activity of empowering others. The symbol of “power over others” becomes transformed to “conscious empowerment of others” through service, leadership, and nurturing support.

Helping people manipulate symbols related to masculinity and femininity requires facing the illusions of gender role stereotypes. For gender role transitions to occur, the artificiality and illusions of gender role stereotypes need to be assessed through the deconstruction process. For example, one illusion is the value of highly sex-typed behavior and masculine and feminine stereotypes as a basis for healthy self-definition. For an evolving person who is seeking transformation, stereotypes no longer have the same power or utility in coping with life events. They recognize that stereotypic masculinity and femininity are not synonymous with health. This recognition represents a significant breakthrough toward a more substantial understanding of gender and human identity. The past gender role stereotypes are exposed as shallow and as not sustaining the person on a deeper, internal level. The illusions of the stereotypes need exploration if real growth is to occur over the lifespan. This process involves capturing deep emotions about masculinity and femininity and finding new meaning in them.

Principles and Parameters of Gender Role Journey Therapy (GRJT)

To journey is to move through time and space for a reason and reach a new place, and therapy can be conceptualized the same way. The notion of a journey can lessen the stigma attached to therapy that can keep men from seeking help. Whether the path is predictable or the direction unknown, journeying implies movement and change. The goal of the gender role journey is to resolve GRC and promote healthy and positive masculinity

The process of journeying with one’s gender roles has been conceptualized from observing students during the gender role journey workshop that was offered for twenty-two consecutive summers at the University of Connecticut (See chapter 13, O’Neil, 1995; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988). Over 700 men and women participated in this six-day, psychoeducational experience and my evaluations of the students’ change processes as they considered whether and how to journey with their gender roles were critical in helping define the gender role journey therapeutic process. Based on those evaluations and past conceptions of men’s therapy reviewed above, six specific principles of gender role journey therapy are presented in Table 4 and elaborated on further in the chapter 10 (O’Neil, 2015 where the stages and processes of change in gender role journey therapy are described.

Table 4: Principles of Gender Role Journey Therapy

| 1 | The three phases of the gender role journey phases can be used as a therapeutic framework to do therapy with men. Clients need to be assessed on which phase of the gender role journey they most closely approximate and their readiness and motivation for change. Clients can be invited or encouraged to take the gender role journey by asking them if they are open to evaluate how restrictive gender roles, sexism, other oppressions have affected them. |

| 2 | The three phases of the gender role journey parallel the stages of change in therapy (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance) and relate to the context of client’s problems and the factors that maintain problems and constrain change (Prochaska and Norcross, 2010; Brooks, 2010). Phase 1 and 2 of the gender role journey are considered to be unhealthy or at least unsettled phases of the gender role journey and reinforce masculine specific conflicts and other problems in men’ lives. |

| 3 | The gender role journey can be a way of helping men discover their masculine specific conflicts and emotional wounds experienced as gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations. Facilitating a client’s gender role journey allows for deepening of the therapy (Rabinowitz and Cochran, 2002) and prompt gender role transitions. The gender role journey serves as a possible portal to men’s problems in therapy. In this regard, the gender role journey and GRC become a “….. a way to organize the thematic elements in the male client’s narrative as well as an entry or key to the deeper, emotional elements of images, words, thematic elements of the client’s inner psychological life (Rabinowitz& Cochran, 2002, p.26). |

| 4 | Providing clients macro-societal and diversity contexts to their gender role journey can help them discern how sexism and other oppressions have contributed to their psychological problems including internalized oppression. Deconstructing masculine and feminine gender roles and stereotypes is the primary way to experience the gender role journey and help men resolve their GRC. Therapists have options when facilitating the gender role journey by using interviewing, consciousness raising, psychoeducation, bibliotherapy, and use of masculinity measures. Psychosocial assessment of the clients’ development, their gender role transitions, and distorted gender role schemas can facilitate the gender role journey. |

| 5 | GRC is a multifaceted dynamic for both clients and the therapists and needs to be monitored during therapy for positive therapy outcomes. Clients’ GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) can be a defenses that hide the portal and the masculine specific conflicts and inhibit movement through the gender role journey phases and the levels and processes of therapeutic change (Prochaska and Norcross, 2010; Brooks, 2010). Psychological defenses may need to be assessed and worked with during the gender role journey. Assessing a man’s masculinity ideology, patterns of GRC, and distorted gender role schemas is critical during therapy. Helping clients transition from one phase of the gender role journey to another by assessing and resolving the patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) can increase the deepening during the therapeutic process. Assessing how the man devalues, restricts, and violate himself and others is key to finding the portal and resolving the GRC. Healing from gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations requires insights assertiveness, self-efficacy, risk taking, and personal and professional activism. |

|

6 |

Normalizing human vulnerability, wounds, and pain is critical to facilitating the gender role journey. Contextually, GRC may be a man’s wound, may conceal a man’s wounds, and may be a vehicle to discovering a man’s wounds. The critical issue of transitioning men from one stage of change to another through the phases of the gender role journey occurs best with the resolution of the RE, SPC, homophobia, and control issues. |

| From: O’Neil, J.M. (2015) Gender role journey therapy with men. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 227-248. Washington, D.C. APA Books. | |

Client Symptoms and Dynamics Across the Three Phases of the Gender Role Journey

Table 5 summarizes the stages and phases of change for male clients and their therapists during the gender role journey, listing possible client’s symptoms and dynamics in each phase of the gender role journey or stage of change. Furthermore, possible interventions for therapists are also listed for each phase of the gender role journey and stage of change. Ninety client symptoms or therapeutic states are listed in Table 5 and almost 80 action oriented interventions for the therapist are enumerated. The summary of this information defines GRJT in very operational terms and adds to the early work that Brooks (2010) did integrating transtheoretical therapy with masculinity conflicts. The list should be useful in preparing diagnostic process-oriented assessments and interventions during men’s gender role journeys. The table can be used to find men’s portals (Rabinowitz & Cochran, 2002) and determine their readiness for change (Brooks, 2010). Since every client and therapy process is different, Table 3 serves as a template to generate hypotheses about how to intervene, when, and with what expected outcomes, based on the stage of change and phase of the gender role journey.

| Table 5 Summary of Stages and Phases of Change For Male Clients and Their Therapist | |

| Precontemplative Stage & Phase 1 - Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles | |

| Client Symptoms & Dynamics In Each Stage or Phase | Possible Interventions For Therapists |

| Is unaware of any gender role problems | Defines the gender role journey |

| Has dualistic-categorical thinking | Experiments with strategic interventions |

| Has unconscious GRC | Show patience and invest in bonding with client |

| Receives rewards for stereotypic attitudes & behaviors | Use masculine terms for helping (i.e., coaching) |

| Is unsure whether there is a problem | Show patience & Invests in bonding with client |

| Has limited awareness about sexism | Use masculine terms for helping (i.e. coaching) |

| Has limited how sexism devalues, restricts, & violates people | Use small talk if appropriate |

| Has irritation when traditional gender roles are violated | Assesses stage of change, readiness, and motivation |

| Devalues, restricts, violates self and others | Use humor to connect with client |

| Restricts friends to those who endorse his gender role values | Make self-disclosures to deepen the therapy |

| Has mostly superficial & distant relationships with others | Show high respect and honors the client |

| Has RE and RABBM | Affirms client’s strength and courage |

| Has rigid and strong defenses | Recognizes that therapy may be GRC for the client |

| Devalues emotional expressions | Explores false assumptions about gender roles |

| Has anger, maybe the only emotion | Assesses clients capacity for talk therapy |

| May work to preoccupy self to avoid emotions | Administers masculinity measures |

| Thinks power and control are important to protect self | Gets permission to ask questions & make comments |

| Has distorted gender role schemas | Addresses self-blame and blaming others |

| Has masked vulnerability | Listens to the client’s story |

| Is unaware of macro-societal effects of sexism & oppression | Assesses client’s experience with losses of control |

| Has limited awareness about his psychosocial development | Encourages increased self-talk |

| Has limited appreciation for diversity & multiculturalism | Offers options and opportunities |

| Experiences difficulties making gender role transitions | Tailor options to the clients’ comfort |

| Becomes a no show or terminate prematurely | Introduces a pain paradigm |

| Feels therapy stigmatizes him | Establishes a therapy structure |

| Makes mutually agreed upon goals | |

| Explains how diversity affects men | |

| Does consciousness raising around men’s issues | |

| Considers bibliotherapy with client | |

| Assesses distorted gender role schemas | |

| Defines internalized oppression | |

| Discusses the negative consequences of GRC | |

| Asks how masculinity conflicts affects functioning | |

| Introduces masculinity concepts into therapy | |

| Introduces psychosocial concepts into therapy | |

| Prepares client for emotional management | |

| Assesses physical health issues | |

| Contemplative Stage & Phase 2 - Gender Role Ambivalence, Confusion, Anger, & Fear | |

| Client Symptoms & Dynamics In Each Stage or Phase | Possible Interventions For Therapists |

| Accepts the reality of his problem | Looks for the portal |

| Has some trust of the process, the therapist, & self | Deepens the therapy |

| Has hope for positive outcome | Recommends increased internal dialogue |

| Vacillates on whether to follow through | Brings out more salient gender role issues |

| Gets stuck in thinking and procrastinates | Assesses distorted gender role schema |

| Identifies those who have judged him | Address false assumptions on an emotional level |

| Is Confused about gender role identity | Assesses and discusses devaluations, restrictions, & violations |

| Vacillates between safety of stereotypes and eliminating them | |

| Deconstructs gender roles | Assesses shame and guilt |

| Has openness to change and gender role transitions | Introduces the pain paradigm again |

| Is Ambivalent about the usefulness of stereotypes | Encourages journeying and letting go of pain |

| Has greater awareness of macro-societal oppression | Helps calculate costs vs. benefits of changing |

| Continued dissatisfaction with stereotypic gender roles | Assesses gender role losses |

| Has increased awareness that sexism violates people | Introduces the notion of risk |

| Has some vagueness on how sexism operates | Encourages monitoring of triggers of emotions |

| Slips into denial about effects of gender roles | Prepares the man for being blamed or criticized |

| Has confusion by the emotional aspect of his problem | Monitors power issues with client |

| Recognizes in a greater way that sexism hurts people | Refocuses client on pain and wounds |

| Identifies distorted gender role schema | Discusses the strength of vulnerability |

| Experiences difficulty redefining distorted gender role schemas | Helps work through internalized oppression |

| Experiences difficulty calculating cost/benefit of changing | Stimulates deep emotions about damaging GRC |

| Experiences difficulty taking action with GRC | Helps client use anger as a vehicle for change |

| Has worries and fears about giving up old masculine identity | Helps client create metaphors for healing |

| Experiences losses as gender roles are deconstructed | Creates discomfort that prompts action |

| Contemplates making change | |

| Has no firm commitment to change | |

| Has lingering confusion about his problem | |

| Has a seriousness about the problem but not ready to act | |

| Becomes more flexible in evaluating himself cognitively and emotionally | |

| Takes baby steps with his problem | |

| Has no real plan to change | |

| Is ambivalent about taking action | |

| Sees himself differently but is unsure how to actualize the change | |

| Becomes more open to evaluate his behavior | |

| Accepts that he has GRC | |

| Experiences impatience with therapy | |

| Preparation Stage & Phase 2 - Gender Role Ambivalence, Confusion, Anger, & Fear | |

| Client’s Symptoms & Dynamics In Each Stage or Phase | Possible Intervention For Therapists |

| Intends to act soon | Helps client negotiate plan |

| Reports baby steps | Brainstorms a plan with a client |

| Has increased negative emotions about sexism | Coaches client on plan |

| Has increased stress about sexism and personal change | Gives examples of others that changed GRC |

| Narrows circle of friends to those who support him | Encourages client to read about other men |

| Gets stuck in his anger sometimes | Encourages positive use of anger |

| Feels immobilized sometimes | Discuss self-liberation |

| Is confused and doesn’t know what to do | Discuss calculated risk taking |

| Knows he needs to develop a plan | Helps create a network of support |

| Needs to make a commitment to change | Reviews triggers of vulnerability |

| Is uncertain about what gender role issues need to change | Reviews plans of action |

| Feels less ambivalent but still can’t act | Prepares client for disconfirmation |

| Has doubts how gender role transitions will work out | Helps client develop plan for disconfirmations |

| Is unsure how to pull off the personal change | |

| Decides how to use his anger | |

| Decides whether to become an activist | |

| Continue to work on assertiveness | |

| Continue to work on increasing self-confidence | |

| Action-Maintenance Stage & Phase 3 - Personal and Professional Activism | |

| Client’s Dynamics and Symptoms In Each Stage or Phase | Possible Interventions For Therapists |

| Takes positive action | Affirms client activism |

| Modifies his behavior to overcome problems | Gives ongoing affirmation and support |

| Reaffirms commitment to change | Encourages independence from therapy |

| Devotes considerable amount of time to making change | Helps trouble shoot when there are problems |

| Continues to change self | Encourages client to build in reinforcers |

| Become involved in changing oppressive structures | Celebrates client’s renewal & transformation |

| Implements plan of action | |

| Deals with disconfirmation | |

| Continues to seek role models and mentors | |

| Stays healthy | |

| Monitors possible relapse | |

| Celebrates success in renewing and transforming self | |

O’Neil, J.M. (2015) Gender role journey therapy with men. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 227-248. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

Therapeutic Strategies to Resolve Patterns of GRC: SPC, RE, RABBM, and CBWFR

Of course, the real question is how to help men in therapy with their GRC in a very practical sense. Table 6 lists the four patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) and specific strategies that can be implemented to resolve it and promote movement toward problem solving and healing. Helping men learn how to label, experience, and discharge emotions may be the most important activity to pursue. To change RE requires both factual knowledge about emotions and practice in expressing feelings. SPC also needs to be redefined, and exposing the illusions about success, control, and power can be eye openers, particularly when the severe costs incurred are identified. When RABBM is worked through, the client has more opportunities to actually practice getting close to other men and deconstruct homophobic and heterosexist attitudes. Exploring body awareness and doing more self-disclosure with other men as part of therapy homework assignments can be useful activities that move the man along to action and activism. In the same way, therapy can be a laboratory for men to resolve CBWFR through learning better time management, prioritizing, and managing stress in new way.

| Pattern | Strategies |

| SPC (Success, Power, and Competition) | Recognize difference between power-control over others, sharing power, and empowering others category of power

Accepting the lack of control in certain situations and being comfortable and confident with letting of control “if necessary” Redefining success outside the capitalist and economic realms; humanizing success Discussing new ways to validate ourselves rather than through winning and competing against ourselves Redefine losing not as a failure as a man Engage non-competitive activities |

| RE (Restrictive Emotionality) | Teach emotional vocabulary

Read about emotional intelligence Discuss advantages of a fluid emotional life Project the cost of emotional restriction over 10 year period Analyze emotional charged scripts Keep an emotional diary, log, or journal Redefine emotional in human terms Role play feelings Perl’s empty chair ‘talking to your feelings” Analyze family members, peers, and colleagues’ emotional capacity |

| RABBM (Restrictive and Affectionate Behavior Between Men) | Defining and understanding homophobia and heterosexism

Understanding how homophobia and heterosexism separates and restricts men Differentiating sexual issues from human intimacy and affection Exploring body awareness Practicing giving men compliments and receiving them Understanding body mind splits Practicing self-disclosure with other men |

| CBWFR (Conflict Between Work and Family Relations) | Redefine success at work and in the home

Learn time management skills Show self-compassion for work/family stressor Prioritize and plan more Take turns with spouse Learn stress management Lower criteria for success at work and home based on situation and contingencies |

| *Table 4 refers to title in the referenced paper (below). There is not a drop down missing | |

| From: O’Neil, J.M. (2015) Gender role journey therapy with men. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp 227-248. Washington, D.C. APA Books. | |

The Gender Role Journey Workshop

Publications on the Gender Role Journey Workshop

O'Neil, J. M. & Roberts Carroll, M. (1988). A gender role workshop focused on sexism, gender role conflict, and the gender role journey. Journal of Counseling and Development, 67, 193-197

O'Neil, J.M. (1995). The gender role journey workshop: Exploring sexism and gender role conflict in a coeducational setting (Ed.). Men in Groups: Insights, interventions, psychoeducational work. Washington, D.C.: APA Books.

O’Neil, J.M. (2000) Review of the Gender Role Journey Measure (GRJM). In J. Maltby, C. Lewis, & A. Hill (Eds.) Commissioned reviews of 250 psychological tests. Credigion, Wales: The Edwin Mellon Press.

O’Neil, J.M. (2015). Prevention of gender role conflict using psychoeducation: Three evaluated interventions. In J.M. O’Neil, Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change, pp. 313-335. Washington, D.C. APA Books.

The Gender Role Journey Workshop For Men and Women

O'Neil, J. M. & Roberts Carroll, M. (1988). A gender role workshop focused on sexism, gender role conflict, and the gender role journey. Journal of Counseling and Development, 67, 193-197.

A 6-day, 36-hour gender role journey workshop designed to help adults analyze their gender role socialization and conflict was offered from 1984 to 2006 with over 700 men and women participating (O’Neil, 1995, 2015; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988). The workshop’s conceptual base encouraged participants to examine their present and past experiences with gender roles. The four major concepts of the workshop were sexism (Albee, 1981), gender role conflict (GRC), gender role transitions, and the gender role journey (O’Neil & Egan, 1992a)

Workshop Dimensions

Assumptions and Workshop Principles

The workshop design assumed that adults need to talk with each other about sexism and gender role conflicts as part of the healing process. Additionally, it was assumed that alliances between men and women were possible and necessary for the growth and understanding of each sex. It was also assumed that discussions about gender roles and sexism can be difficult, dynamic, and emotional.

Six principles guided the workshop’s preparation and implementation. First, men and women struggle to integrate new definitions of gender roles as they face life events. Second, varying degrees of awareness about the negative outcomes of restrictive gender roles and sexism exist in people’s lives. Third, an expanded “gender role vocabulary” is needed to express thoughts and feelings on changing gender roles. Fourth, conflicts and negative emotions occur as men and women become aware of sexism. Fifth, understanding and resolving gender role conflicts (GRC) can occur using the phases of the gender role journey (See chapter 3, 5, & 10). like those in Table 1. Finally, dialogue about gender roles and sexism can be constructive and nonviolent if there is a commitment to mutual support and understanding.

Workshop Participants

Separate workshops were offered over a 24 year period, but specific evaluation data were gathered in the 1985, 1986, and 1987 workshops with a total of 84 participants enrolling from counseling, teaching, nursing, and other helping professions. Women outnumbered men three to one in each workshop and the average workshop size was 28 participants. The mean age of participants was 33, 38, and 36 for Workshops I, II, and III, respectively. The workshop leaders were one male Ph.D. level counseling psychologist and one female master’s level counselor.

Workshop Curriculum, Process, Norms, and Media

Workshop curriculum. The workshop’s title was “Gender Role Conflict Issues for Helping Professionals.” but over the years the unofficial title was the Gender Role Journey Workshop. It was offered as a graduate summer school class in the Counseling Psychology Program in the Educational Psychology Department at the University of Connecticut. The curriculum of the workshop is summarized in detail in Table 4. During each day of the workshop, new themes were introduced using lectures, music-media, structured-experiential exercises, and small-large group discussions. Mini-lectures, media presentations, and personal self-disclosures were the primary modes of teaching and learning.

The curriculum established specific definitions of gender role concepts through preassigned readings and lectures. This common terminology provided a concise understanding of the relationship between socialized gender roles and sexism. Furthermore, the workshop curriculum presumed that sexism is a form of violence between and among men and women and, therefore, a potentially volatile interpersonal issue. Consequently, the curriculum was defined as a vehicle for people to discuss nonviolently the effects of sexism, using the gender role journey.

The curriculum was designed to elicit personal exploration in both the cognitive and affective domains of learning by using theory, research, and group activities. The curriculum was developed so that the ongoing group process would become part of the workshop content. Group leaders helped participants identify specific examples of sexism and GRC as they occurred with and between group members. Greater personalization of the curriculum was possible by using music, movie clips, self-assessments, and group activities. Also, personal disclosures by the leaders and presentation of famous person’s gender role journeys (e.g., John Lennon, Jane Fonda, and Marvin Gaye) provided a basis for participants’ own assessment of their journeys and conflicts.

Workshop process. Before the workshop, participants read five manuscripts providing background on gender roles and sexism (See O’Neil, 1995 and O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988). These readings focused on men’s sexism and gender role socialization, but equal time was given to women’s issues in the lectures and the media used. A preworkshop needs assessment was administered through the mail to assess participants’ expectancies, needs, and attitudes about gender roles. These data were gathered to better understand the participants and allow their direct input into the workshop design. Participants filled out daily evaluation forms assessing the day’s activities and process. These daily evaluations provided feedback for preparing the next day’s workshop content and process. On the last day of the workshop, participants prepared action plans, specifying in detail what they could do about sexism personally, professionally, and politically over the coming months.

Workshop norms. Specific norms were established early in the workshop and guided the group process. The following workshop norms were established and monitored during the 6 days: (a) personal comfort and safety; (b) freedom of movement and self-expression; (c) interpersonal respect; (d) personal nonviolence; (e) emotional and intellectual expressions; (f) nonviolent expressions of anger; (g) prohibition of victimization and interpersonal violence; (h) mutual support; (i) self-assessments, self-disclosures, and positive regard for individual differences; (j) careful listening and “tracking” the group process; (k) monitoring personal “talk time” in the group; and (l) developing friendships and alliances with others.

Media and stimulus diversity. Lectures and audio-video media were used continuously throughout the workshop as part of the stimulus diversity (see Table 4). Stimulus diversity was defined as employing sequential teaching interventions to stimulate personal feelings, thoughts, and self-exploration. An example of how stimulus diversity worked in the workshop was the video presentations of the gender role journeys of John Lennon, Jane Fonda, and Marvin Gaye in the early years and Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, Elton John, Hillary Rodman Clinton, and Roger Maris after 1995. Their journeys were documented using various stimuli including biographical profiles, music videos, and movie clips. Workshop participants could personalize their gender role issues by observing real life dramas of sexism from famous people’s lives.

Results of the Workshop Evaluations

The evaluation data came from self-report questionnaires that were descriptive and global in nature. Evaluations of all participants were conducted before and during the workshop, immediately after the workshop, at 1- and 3-month intervals after the workshop, and at 1 and 2 years after the workshop.

Likert scale items assessed personal learning form the workshop, emotional reactions to the workshop, and the degree that the workshop personally affected participants over a 1-month period. Percentage agreement on each item for Workshops I, II, and III, respectively, is found within the parentheses for each item. In reference to personal learning, participants indicated: learning more about themselves (100%, 100%, and 89%); having a better understanding of their socialization process (88%, 96%, and 92%); having greater understanding of their relationships with their mother and father (84%, 76%, and 77%) and having increased sensitivity as to how stereotypes damage men and women (100%, 100%, and 96%). Regarding emotional reactions, participants indicated; having felt emotional pain from issue(s) that emerged during the workshop (84%, 57%, and 52%); and having cried since the workshop because of pain experienced in the workshop (64%, 38%, and 19%). In reference to the degree of impact of the workshop, participants indicated that: personal disclosures during the workshop continued to affect them (88%, 76%, and 78%); the workshop affected their relationships with the most intimate people in their lives (84%, 71%, and 59%); the workshop permanently altered their views of male-female relationships (68%, 86%, and 69%); and the workshop empowered them to affect change with gender role conflict in people’s lives (80%, 91%, and 74%).

Participants in Workshop I were sent a follow-up questionnaire 2 years after the workshop, and Workshop II participants received the same questionnaire 1 year later. These extended follow-ups assessed whether participants had taken action as planned on the last day of the workshop, as well as the overall impact of the workshop. Over 70% of the participants indicated they had carried out some of their personal and professional action plans, whereas 50% of Workshop I and 29% of Workshop II participants indicated that they had implemented some of their political action plans over both time periods. Finally, over 87% of the participants indicated that the workshop continued to influence their lives either 1 or 2 years later.

Discussion

The workshop created an environment supporting dialogue about GRC and sexism using the gender role journey metaphor. The evaluation data indicated positive reactions to the workshop as participants reported personal learning, emotional experiences, and continued impact over time. A majority of the respondents indicated they had implemented some of their personal and professional action plans when contacted 1 or 2 years later.

The workshop is one example of how research and theory on gender roles can be translated to therapeutic experiences for adults. Helping men and women build alliances within themselves and with each other is important in the ongoing gender role dialogue. Counselors and psychologists, committed to more humane and nonviolent relationships between and among the sexes, have much to offer adults by encouraging mutual alliances in the gender role journey and the prevention of sexism (Albee, 1981).

TABLE 4

Dimensions and Curriculum of Gender Role Journey Workshop1

| Workshop Dimension | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 |

| Themes | Workshop norms & expectations

Gender role journey phases How to access the workshop Stages of a group Understanding the group process Power & oppression Men & women as victims of sexism Metaphors for healing Power & control issues in the workshop |

Research on sex differences, gender role socialization, & stereotyping

Patriarchy, sexism, oppression, & violence Working with emotional pain Working with defense mechanisms |

Patterns of men’s & women’s gender role conflict | Adult life cycle & gender role transitions & themes | Family socialization & mothers, fathers, sons, & daughters

Sexual orientation, race, class, ethnic background, & gender role socialization |

How to keep the gender role journey going

Action plans & goals Summary of workshop Community lunch closure & goodbye |

| Lecture topics | Rationale & norms for workshop

Summary of need assessment data Gender role vocabulary Four kinds of violence Sexism, racism, classism, homophobism, & ethnocentrism as violence The gender role journey Leader’s disclosure on gender role journey

|

Research on sex differences & gender role socialization

Gender role restrictions, devaluations, & violations Pleck’s (1981) sex role strain analysis Gilligan’s (1982) In a Different Voice Jeanne Block’s research Matthew Fox’s via negative |

Men’s perceived losses of power

Men’s patterns of gender role conflict (O’Neil, 1981a, 1981b) Men’s fears of femininity & masculine mystique Women’s patterns of gender role conflict Research on men’s gender role conflict Leader’s disclosure on patterns of gender role conflict |

Adult life cycle stages

Gender role transition & themes John Lennon’s gender role journey Methods of transformation & gender role transitions |

Data on victimization & violence in the United States

Marvin Gaye’s gender role journey Leader disclosures: father-daughter relationships Jane Fonda’s or Marilyn Monroe’s gender role journey Healing the wounds Definitions of racism & classism |

Working with pain over time

Developing action plans How to use the workshop content Reentry issues & problems Purpose & function of action plans |

| Music & media used | Music

Concerto no. 1 in A Minor (Bach) “Unity” (Holly Near) Four Seasons (Vivaldi) “Homecoming Queen’s Got a Gun”; “I like ‘em big and Stupid” (Julie Brown) “The Way We Were” (Barbara Streisand

Music videos “That’s What Friends Are For” (D. Warwick, E. John, S. Wonder, & G. Knight)

Movie clips Nine to Five |

Music

“Between Two Worlds and Forever the Optimist” (Patrick O’Hearn) “Candle in the Wind” (Elton John)

Music videos “Cry” (Godley and Crème) “Oh Father” (Madonna)

Movie clips Thelma and Louise |

Music

“Free to Grow”; “Feeling Better” (Holly Near)

Music videos “I Want to Know What Love Is” (Foreigner)

Movie clips Tootsie Superman III |

Music

“American tune”; “A Bridge Over Troubled Water” (Simon & Garfunkel) “Double Fantasy” (John Lennon & Yoko Ono) “From the Goddess” (On the Wings of Song and Robert Gass)

Music videos “Woman is the Nigger of the World”; “Mother”; “Woman”; “Imagine” (John Lennon)

Movie clips Kramer vs. Kramer |

Music

“Child” (Holly Near)

Music videos “Motown Anniversary Video”; “What’s Going On”; “Sexual Healing” (Marvin Gaye) “Missing You” (Diana Ross) “The River” (Bruce Springsteen)

Movie clips On Golden Pond Ordinary People The Honeymooners (Jackie Gleason) Mississippi Burning |

Music